The Old Bailey Proceedings, 1674-1834

Evaluating and annotating a corpus of 18th- and 19th-century spoken English

Magnus Huber,

Department of English,

University of Giessen

1. Introduction

In their search for records of authentic spoken language predating the invention of audio recording technology in the second half of the 19th century, historical linguists have turned to written genres that are believed to be closer to speech than the average written document. Such genres include drama, dialogue in prose fiction, sermons, and trial proceedings.

The proceedings of the Old Bailey, London's central criminal court, were published from 1674 to 1834 and constitute a large body of texts from the beginning of Late Modern English. The Proceedings contain over 100,000 trials, totalling ca. 52 million words and its verbatim passages are arguably as near as we can get to the spoken word of the period. The material thus offers the rare opportunity of analyzing everyday language in a period that has been neglected both with regard to the compilation of primary linguistic data and the description of the structure, variability, and change of English.

The time span covered by the corpus and the available sociobiographical speaker information allow fine-tuned studies, including historical sociolinguistic approaches. In addition, because of sheer size the Proceedings are a valuable textual source for the analysis of low-frequency features. For instance, an analysis of the present and past tense forms of the ten most frequent verbs in the Proceedings (know, go, see, say, take, live, come, give, get, tell) shows that overt inflection in the first person singular (e.g. I says, mostly with past reference) has a very low frequency of just over 0.1%. Analysing such marginal phenomena is impossible with most existing historical corpora, running up to a couple of million words at most. By contrast, since the total number of 1sg forms of these ten verbs amounts to over half a million tokens in the Proceedings, 0.1% corresponds to 547 tokens of inflected 1sg forms, enough for a basic multivariate analysis.

The Old Bailey Corpus (OBC) is based on the Proceedings and documents spoken English from the 1720s onward. Digitized transcripts of the Old Bailey Proceedings were obtained from Robert Shoemaker (Department of History, Humanities Research Institute, University of Sheffield) and Tim Hitchcock (Department of History and Social Sciences, University of Hertfordshire). Turning the digitized transcripts into a linguistic corpus consists of two main stages:

- localization and tagging of direct speech in the 52 million word pool corpus, and

- sociolinguistic mark-up based on sociobiographical speaker data found in the context.

This article will start with an overview of the historical background and the structure of the Proceedings, the 'raw' material that is being turned into the OBC. Section 3 will be concerned with assessing the linguistic reliability of the OBC as a linguistic source, relying on linguistic and extra-linguistic evidence. These sections demonstrate that the annotation of early trial proceedings has to be preceded by a consideration of the complex issues surrounding the genesis and the conventions of this genre. The annotation process in compiling the OBC will be described in Section 4.

2. The Old Bailey and the Proceedings

London's Central Criminal Court is still known as the Old Bailey, after the street near St. Paul's Cathedral where the courthouse is located. Its original jurisdiction was London and Middlesex and up to the early 19th century the court met eight times a year. In 1834 the Old Bailey was renamed Central Criminal Court, its jurisdiction enlarged to include parts of the neighbouring counties and the yearly sessions increased to twelve. Most of the people tried at the Old Bailey came from the capital, although there are also cases of prosecutors, defendants and witnesses from other parts of the country or even from abroad. [1]

The first published accounts of trials at the Old Bailey are from 1674 and were entitled News from Newgate: OR, An Exact and true Accompt of the most Remarkable, TRYALS OF Several Notorious Malefactors: At the Gaol delivery of Newgate, holden for the CITY of LONDON, and COUNTY of MIDDLESEX. In the Old Baily … (16740429). [2] Towards the end of that year, the title was changed to News from the Sessions, OR, A True Relation of all the PROCEEDINGS AT THE Sessions in the Old bayly … (16740909) and the reports continued to be published as the Proceedings until 1834, the end of the period considered in this article.

The Proceedings started as commercial enterprise. True crime sold well, so publishers sent scribes to the Old Bailey, who recorded the trials in shorthand. Because of their sensationalist stance, early Proceedings are rather judgmental. Gradually, however, the City of London gained more and more control over the publications. As early as 1679, the Court of Aldermen in London ordered that accounts of proceedings at the Old Bailey could only be published with the approval of the Lord Mayor and the other justices, and accordingly the tone gets more objective. Over the 18th century, the Proceedings develop into official records of the trials at the Old Bailey. In 1778 the City stipulated that they should represent a 'true, fair, and perfect narrative' of what happened in court and from 1787 it paid a subsidy to the publisher to ensure continued publication. Because the Proceedings had come to be considered official records, the publisher was required to supply 320 free copies to the City.

2.1 The Old Bailey Proceedings Online

The 1,219 surviving Proceedings published between 1674 and 1834 were digitized by the Humanities Research Institute, University of Sheffield, and the Higher Education Digitisation Service, University of Hertfordshire, directed by social historians Robert Shoemaker and Tim Hitchcock. The material can be searched and accessed at the Old Bailey Proceedings Online and contains over 100,000 trials, totalling ca. 52 million words. The website also contains images of the original pages of the Proceedings. [3]

The Old Bailey Proceedings Online is an extremely valuable resource. The site contains helpful background information on the publication history of the Proceedings as well as on the historical background of crime and justice in the London from the late 17th to the early 19th centuries. Most importantly, it provides access to the unique collection of primary sources through a sophisticated search engine. The Proceedings can be searched by keyword, person name, place, crime, verdict and punishment. There is also an advanced option that combines several parameters for more complex searches.

However, the Old Bailey Proceedings Online was not created for the needs of linguists. While some degree of linguistic analysis is possible, the possibilities to search for high-frequency functional morphemes — a major interest in corpus linguistics — are rather restricted. Since the online Proceedings contain over 50 million words, the search engine initiates a search by consulting Lucene indices rather than performing a full-text search. This makes online searches very quick and returns hundreds to thousands of results in a fraction of a second. These are displayed in the manner of a concordance with links to the individual trials containing the search word.

As mentioned, there are a number of disadvantages for the linguist. First of all, the concordance-like list of hits cannot be manipulated in any way: the search word is not centered, there is only one concordance entry per trial even though this may contain several hits, and there is no way of sorting or deleting entries. While this is awkward for linguistic purposes, the most significant drawback is that search words are not allowed to begin with wild cards, which makes searching for inflections impossible. In addition, in order to speed up retrieval, the function words a, and, are, as, at, be, but, by, for, if, in, into, is, it, no, not, of, on, or, such, that, the, their, then, there, these, they, this, to, was, will, with are not included in the indices and can thus not be searched for. For the historical sociolinguist, there is the further restriction that the advanced search function does not include a keyword search. To take an example: while it is possible to retrieve all trials that include female defendants between the age of 20 and 30 (in order to e.g. compare them to other age groups), one can not search for female defendants between 20 and 30 who use, for example, don't (as opposed to do not). The latter would have to be done manually, by copying the trials (and there are 3,453 in this particular case!) and performing the text search in a different program. One can limit searches to particular parts of the Proceedings (front matter, trials, punishment summaries, etc.), but not to spoken language alone, since that was not tagged in the electronic version of the Proceedings.

2.2 Sociobiographical characteristics of speakers in the Old Bailey Proceedings

Figure 1 is based on Table 1 and shows the age structure of persons involved in the trials at the Old Bailey, based on the information in the Old Bailey Proceedings Online statistics search function:

Table 1. Age structure of participants in the Old Bailey trials.

Age |

1670- |

1680- |

1690- |

1700- |

1710- |

1720- |

1730- |

1740- |

1750- |

1760- |

1770- |

1780- |

1790- |

1800- |

1810- |

1820- |

1830- |

0-10 |

5 |

14 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

8 |

1 |

5 |

16 |

8 |

37 |

12 |

35 |

47 |

40 |

29 |

11-20 |

25 |

36 |

15 |

0 |

5 |

13 |

12 |

11 |

32 |

139 |

81 |

210 |

1388 |

1931 |

3845 |

5298 |

2633 |

21-30 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

13 |

2192 |

3647 |

5191 |

4253 |

2248 |

31-40 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

1120 |

2098 |

2653 |

1757 |

856 |

41-50 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

579 |

1080 |

1453 |

966 |

400 |

51-60 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

297 |

545 |

782 |

464 |

198 |

60+ |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

10 |

142 |

275 |

353 |

236 |

75 |

Figure 1. Age structure of participants in the Old Bailey trials.

Note that the figures also include the age of persons only mentioned during, but not necessarily present at, the trials. Nevertheless, the above gives a good impression of the situation: only from the 1790s onwards is age more systematically mentioned in the original Proceedings (and therefore tagged in the electronic version), and only from then on is the age structure of society more accurately reflected in the markup. The aim is to provide more age information for the time predating the 1790s during the annotation of the OBC.

The gender structure of the speakers in the Proceedings is indicated in Table 2 and Figure 2. Since speech passages and speakers are not identified in the original electronic version, an indirect approach via the sex of the defendants was taken here.

Table 2. Defendant gender structure in the Old Bailey Proceedings Online.

| Gender |

1670s |

1680s |

1690s |

1700s |

1710s |

1720s |

1730s |

1740s |

1750s |

1760s |

1770s |

1780s |

1790s |

1800s |

1810s |

1820s |

1830s |

| M |

415 |

2341 |

2386 |

472 |

2150 |

3640 |

3517 |

3051 |

3154 |

3501 |

5614 |

7374 |

5441 |

6589 |

11719 |

17786 |

8968 |

| F |

159 |

916 |

1695 |

487 |

1390 |

2152 |

2082 |

2006 |

1672 |

1565 |

2216 |

2438 |

1820 |

2597 |

3355 |

4374 |

2353 |

Figure 2. Defendant gender structure in the Old Bailey Proceedings Online.

On average, 72.6% of the defendants are men, and it is expected that the final version of the OBC will contain roughly the same percentage of male speakers. It might be objected that a corpus for sociolinguistic research should aim for a balanced representation of the genders, but this is impossible with the Proceedings since the trials always involve males (judges, prosecutors, lawyers, etc. were exclusively male) but not necessarily females. In addition, the very high number of speakers ensures that even in decades where the percentage of women is low, as in the 1820s and 1830s, their absolute number is still in the thousands.

The Old Bailey Proceedings Online lists over 4,000 occupations and status labels of the participants in the trials at the Old Bailey, from accoutrement-maker to yeoman. These labels are given in their original spelling, they are sometimes more detailed than one would need them to be (for example we find servants to blacksmiths, to gentlemen, to goldsmiths, to leather-sellers, to midwifes, to poulterers, to public houses, to washerwomen, etc.). After standardization of these labels, the actual number of occupations will be much lower and easier to handle for the end user.

The above-mentioned constraints limit the usefulness of the Old Bailey Proceedings Online for linguistic purposes and were one of the motivations for turning the Proceedings into a linguistic corpus. Since the Proceedings cannot be downloaded from the website in their entirety and individual trials are only displayed as raw text, without tags, a copy of the XML-tagged version was obtained from Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker. This version is currently annotated by myself and my team. The major task is to identify speech passages and link them to sociobiographical speaker parameters such as sex, age, or profession.

3. The reliability of the Old Bailey Proceedings as a linguistic source

This section starts with a description of how spoken language is distributed in the Proceedings. This will be followed by two subsections assessing the reliability of these trial accounts as a linguistic source, first by considering external factors surrounding the genesis of these texts and by comparing a trial from the Proceedings to an alternative account (3.2), and second, by testing their internal linguistic consistency through a quantitative analysis of negative contraction (3.3).

3.1 Spoken language in the Old Bailey Corpus

Figure 3 shows the number of 1st and 2nd person singular and plural pronouns as a rough measure of the amount of direct speech reported in the first six decades of publication of the Proceedings. Figure 4 relates the number of pronouns to the total number of words by indicating mean frequencies of pronouns. The reason for relying on this indirect approach via pronouns is that formal text-structuring conventions of marking direct speech varied a lot in the early years and makes automatic tagging (see 4.2) almost impossible. The pronoun forms counted are I, my, mine, me, myself, you, your, yours, yourself, yourselves, thou, thy, thine, thee, thyself, thee, we, ours, us and ourselves. Our was excluded because it frequently occurs in 'our Lord the King'. As there are a number of alternative versions of the Proceedings in the early years, only the longer version was included in the count.

Figure 3. Absolute number of 1st and 2nd person pronouns by year.

Figure 4. Mean frequencies of 1st and 2nd person pronouns per 100 words by year.

The figures show that direct speech became more common only in the 1720s, although there is some measure of spoken language even in earlier trial accounts, particularly in the 1674-1679 and 1692-1695 periods. The comparatively high amount of direct speech in 1678, 1692 and 1706 is due to individual Proceedings, 16781211, 16920406 and 17061206, which report considerably more spoken language than the other proceedings in those years. A closer look at these pre-1734 Proceedings reveals that a good part of the direct speech was not originally uttered in court but is actually embedded in 3rd person narration. That is, the spoken language reported in these early accounts is not that of plaintiffs, defendants or other participants in the lawsuit but that of a third party, as illustrated by the following excerpt:

Watson for himself said, That being ordered by the Plaintiff to Arrest Dorothy Midgley, when he came to the door, he heard the Boy say, I will run my Spit in some of your guts; but putting him aside, he Arrested his Prisoner, and heard some body cry out, I am killed; upon which he run to him … (16781211-23, my emphasis)

These spoken passages are generally short and there is little information on the sociobiography of the speakers. However, the major limitation of their usefulness is the fact that there is a considerable time lapse (weeks or even months) between the original speech event and its recording. The reliability of the data is further diminished due to the intermediary role of the person reporting the utterance in question, who is the immediate source for what the scribe takes down.

Figure 5 gives the total number of words per decade, as well as the proportion of direct speech from 1734 onwards:

Figure 5. Total number of words per decade and proportion of direct speech, 1734-1834.

From the 1730s onward, a relatively high proportion (almost 85%) of the Proceedings is made up of spoken language. The Proceedings therefore constitute a rich source of data for the study of speech in the 18th and 19th centuries.

3.2 Testing the reliability of the Old Bailey Corpus: external factors

It has been argued that from a historian's point of view the material reported in the Proceedings is rather accurate:

Although initially aimed at a popular rather than a legal audience the material reported was neither invented nor significantly distorted. The Old Bailey Courthouse was a public place, with numerous spectators, and the reputation of the Proceedings would have quickly suffered if the accounts had been unreliable. Their authenticity was one of their strongest selling points, and a comparison of the text with other manuscript and published accounts of the same trials confirms that they accurately report what was said in court. (Hitchcock & Shoemaker 2007b)

But Hitchcock & Shoemaker go on to caution that a comparison with alternative accounts of the same trials show that the Proceedings are not complete — though often the most comprehensive account — and that even the most detailed later Proceedings are only partial transcripts of what was said: 'At the very least, in an attempt to save space, minor details and repetitions, perceived as unimportant, were frequently left out of recorded testimony' (Hitchcock & Shoemaker 2007b). In spite of this, and in the absence of better data, the records of the trials at the Old Bailey are arguably as near as we can get to the spoken word of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

As shown above, about 85% of the text in the Proceedings from the 1730s onwards is direct speech. For a linguist trying to reconstruct the speech of the period, an important development in the Proceedings is the switch from third-person to first-person accounts in the 1710s. The early Proceedings tended to give more or less judgmental — and sometimes sensationalist — accounts of the 'most notable trials', as in the trial of Elizabeth Scot for theft on 16 January 1682:

Extract 1:

Elizabeth Scot was Indicted for stealing Plate, to the value of 30 pounds on the 10 of December from Mr. Comissary of Algare-Parish, which was evidently pro[ven] against her, she being taken with it in her Lap, upon which, [she plea]ded, that she had been drinking, and knew not what she did, but that served not her turn, for she was found Guilty. (u16820116a-1, my emendation)

The detail reported for individual trials increased considerably in the 18th century, when scribes reported witness testimonies, statements and arguments of the prosecution and the defence, cross-examinations, etc. Compare Extract 1 with the following extract from the trial of Elizabeth Whitney on 27 February 1740, which includes monologues as well as shorter question-answer exchanges and amounts to over 1,500 words:

Extract 2:

Elizabeth Whitney alias Dribray, and Mary Nash alias Goulding, were indicted for assaulting George Stacey, in the Dwelling-House of William Needham, putting him in Fear, &c. and taking from him, a Moidore, a Thirty-six Shilling-piece, and 30 Guineas. Nov. 20.

Mr Stacey. On the 20th of November I was going towards Temple-Bar, and the Prisoners followed me, and asked me to give them a Quartern of Brandy, or Gin. I did not value such a little Matter, so I followed them into Needham's House, at the Rose by Temple-Bar, and there we had 3 Quarterns of Gin. […] But getting off my Chair, both of them took hold of me by Force of Arms, and held me so, that I could not help myself. I was a little in Liquor, but not much. I knew very well what I did, and I stood upon my Feet for some Time before they got me down; but at last they did get me down, and I cried Murder! Help, for God's Sake! Whitney told me, if I cried out, she would cut my Throat. They gagged me; and my Mouth was so full of Blood, that I could not speak; and Blood likewise gushed out of my Nose. Then they took from me all my Money; 30 Guineas, and upwards, a Moidore, and a Thirty-six Shilling-Piece. […]

Whitney. Was any Thing found upon me?

Mr Stacey. No, I believe not; but she was a Party concerned: her Hand was in my Pocket, as well as Nash's. They both attacked me; one of them throtled me, and the other robbed me.

Whitney. Was not you in Needham's House before I came in?

Mr Stacey. No; I was not, I followed you in.

Sarah Scot. I have a Sister, (one Murphin) who keeps a Stall at Temple-Bar, and she sent for me that Night, to come and open Oysters for her. […]

The Jury found both the Prisoners Guilty, Death. (17400227-2)

Historical reliability as described by Hitchcock & Shoemaker 2007b is not the same as linguistic reliability. The omission or misrepresentation of factual detail in a historical document does not necessarily mean that the spoken language reported in that same document is unreliable. As an example, I will consider the recording of non-standard features, which could be taken as an indication of linguistic faithfulness. The Proceedings are generally written in standard orthography, but sometimes we find non-standard pronunciation (and morpho-syntax) in individual speakers, such as in the following deposition by an Irishman:

James Fitzgerald depos'd to this Effect: On the 25th of February last, about 11 at Night, O' my Shoul, I wash got pretty drunk, and wash going very shoberly along the Old-Baily, and there I met the Preeshoner upon the Bar, as she wash going before me. I wash after asking her which Way she wash walking: And she made a Laugh upon my Faush, and told me to Newtoner's-Lane. […] (17250407-66)

Non-standard phonological and morpho-syntactic detail of this kind is often found in the speech of Irishmen and other foreigners. A certain degree of stereotyping for comic effect on the part of the scribe cannot completely be ruled out, especially if the speaker in question dominates the trial in terms of length of utterance, as in this case. Incidentally, the publisher 'earned a censure from the City authorities for the 'lewd and indecent manner' in which the trial was reported' (Hitchcock & Shoemaker 2007a, Shoemaker forthcoming), which is an indication of the control that the City exerted not only on what was reported by also on the language in which it was reported (see also 3.3.1).

Sometimes, however, non-standard passages are embedded in otherwise completely serious discourse, with no indication of any comic intentions, as in the testimony of Osborn Jones, possibly a Welshman:

I came home to Tinner ant wass coing into my own Room, put the Prissoner's Wife callt to me and sait Here iss your coot Oman. So I hust her a pit, and ask her why a Tiffel she coudn't keep in her own Hapitation when I wanted my Tinner. So the Prissoners Wife prought out a pag with a crate teal of coolt in it. There was a crate many Pieces, a crate teal pigger as Guineas. […] (17350522-1)

The recording of non-standard features seems to be rather unbiased here and the non-standard spelling faithfully indicates a typical feature of Welsh English, the strong aspiration of voiced plosives (therefore perceived as voiceless by speakers of English English, see e.g. Thomas 1994: 122-123).

Nevertheless, even if the Proceedings were a 100% accurate record of the historical facts (which they are not), this would not automatically mean that the direct speech passages are a completely faithful picture of what was said in court. Written representations of spoken language can be several steps removed from the actual speech act and it is the task of the linguist to reconstruct the original speech event on the basis of the written text. This is what Schneider (2002: 68) calls the Principle of Filter Removal:

a written record of a speech events stands like a filter between the words as spoken and the analyst. As the linguist is interested in the speech event itself (and, ultimately, the principles of language variation and change behind it), a primary task will be to 'remove the filter' as far as possible, i.e. to assess the nature of the recording process in all possible and relevant ways and to evaluate and take into account its likely impact on the relationship between the speech event and the record, to reconstruct the speech event itself, as accurately as possible.

After a categorization of text types and their proximity to speech, Schneider (2002: 73) goes on to say that '[d]irect transcripts are clearly the most reliable and potentially the most interesting among all these text types' and names trial proceedings as characteristic examples of this category. Still, it is clear that as written records, even trial proceedings cannot be a completely faithful representation of the speech event and have to be handled with care. In addition to a consideration of the recording conditions, Schneider (2002: 86) lists internal consistency and external fit as important criteria for assessing the validity of written texts representing spoken language: internal consistency refers to the consistent portrayal of variable features across large corpora, ideally deriving from several sources (e.g. different authors), while external fit measures the degree to which results of analyses based on a specific corpus agree with findings of other studies. Culpeper & Kytö (2000) compare four 17th-century speech-related text-types (witness depositions, trial proceedings, prose fiction, and comedies) with the aim to establish how true they are to the original speech event. Based on the criteria of lexical repetitions, turn-taking features, and single-word interactive features (e.g. demonstrative pronouns), they conclude that 'there is a strong case for drama, but that there is also a case for trial proceedings' (2000: 195). [4])

Kytö & Walker (2003) assess the faithfulness of trial proceedings and witness depositions in representing authentic speech. Although both are purportedly verbatim texts (or at least conventionally assumed to be such), 'one could not expect the same standard of accuracy in quoting spoken interaction as one would when quoting a written text' (224). In addition, they caution that '[e]ven with the most faithful of records, it is to be expected that certain typical features of speech such as false starts, pauses, slips of the tongue, and the like would be filtered out …' (225). This is certainly true for the Old Bailey Proceedings, which for the most part lack some of the non-fluency characteristics of unscripted spoken language, such as hesitations (uhm, er, etc.), unfinished sentences, repetitions, etc. Using sources like trial transcripts one has to bear in mind that the primary aim of the scribe was not to record linguistic detail but the substance of the trial.

Just as Schneider (2002), Kytö & Walker (2003: 228) acknowledge that 'written records of a speech event are susceptible to interference — whether conscious or inadvertent — throughout the production process'. With this in mind, I will now attempt to assess the faithfulness of the spoken language in the Proceedings. Following the agenda set up by Schneider (2002: 86), I will do this by discussing the recording conditions, external fit, and internal consistency.

3.2.1 The genesis of the Proceedings of the Old Bailey: general remarks and recording conditions

From the original speech event during a trial at the Old Bailey to the printed Proceedings, we can distinguish at least five consecutive stages (where t = time):

| t1 | speech event |

| t2 | recording (shorthand, orthographic notes) |

| t3 | preparation of MS for printer (e.g. expanding shorthand notes into orthographic text) |

| t4 | proofreading |

| t5 | typesetting |

Each of these stages could potentially have altered the linguistic material of the utterance. At present it is still unclear whether the Proceedings actually went through t3 and t4 — it is imaginable, though rather unlikely, that typesetters worked directly from the shorthand manuscript. Be that as it may, we have to remove several layers of filters, imposed by the scribes

(first while taking the shorthand notes in court and later when expanding them for the publisher), by the proofreaders as well as printers, by the typesetters and by the publishers (who, in addition to their own idiosyncrasies, might impose a house style).

The accounts were published just a couple of weeks after the trials. For example, the Proceedings of the sessions on the 11 and 12 December 1678 were licensed for publication a mere week later, on 18 December. This practice of rapid publication continued with the much longer later Proceedings (cf. e.g. 18281204, which were published before the end of the year). In fact, once the Proceedings came to be regarded as an official record, the city took an interest in ensuring speedy publication, as can be seen on the title page of the Proceedings published in December 1775:

At a Common Council holden in the Chamber of the Guildhall of the City of London on Friday the 17th of November 1775, A MOTION was made and QUESTION put, That the whole Proceedings on the King's Commission of the Peace, Oyer and Terminer, and Gaol Delivery for the City of London, and also the Gaol Delivery for the County of Middlesex, held at Justice Hall in the Old Bailey, be regularly, as soon as possible after every Session, published by the Recorder, and authenticated with his Name: The same was resolved in the Affirmative. (17751206, my emphasis)

Schneider (2002: 72) mentions 'the temporal distance between the speech event itself and the time of recording' as one parameter influencing the accuracy of the written record as a representation of the original utterance: the longer the interval between the two, the higher the risk of misremembrance. In the case of the Proceedings, t1 and t2 are near simultaneous (the scribe took notes during the utterance) and t3-t5 followed shortly after, i.e. the time factor does not pose much of a problem here.

What seems potentially more problematic is the recording technique used at t2: not all techniques (mechanical recording, shorthand, longhand etc.) are equally suitable to record linguistic detail. Kytö & Walker (2003: 228) mention that one of the factors influencing the reliability of a written record in terms of its faithfulness to the speech event is the script (notes or shorthand) used by the scribe. The (somewhat idealizing) implication is that shorthand is more reliable than notes because the latter are by nature sketchy and would have to be expanded later, relying more or less heavily on the memory of the scribe, while the former records the totality of the event in situ.

3.2.2 The uses and limitations of shorthand transcripts

From at least 1749 onwards, but probably from the very beginning in the 1670s, the proceedings at the Old Bailey were recorded in shorthand. A thorough analysis of 18th-century shorthand practices and their influence on the linguistic reliability of the Old Bailey Proceedings would go beyond the scope of this paper, but a brief overview of the possibilities and limitations of stenography with regard to the faithful representation of the original speech event will show the important consequences that the script has for the preservation of linguistic detail.

One of the more influential and popular 18th-century shorthand systems was developed by Thomas Gurney, the scribe who took down the Proceedings from at least 1749 to his death in 1770. Gurney's Brachygraphy or short-writing first appeared in 1752, ran through twelve editions in the 18th century and was reprinted several times in the 19th century. If we assume that in recording the trials Thomas Gurney, and later his son Joseph, who succeeded his father in 1770, used a shorthand system identical or similar to that described in Brachygraphy, then a closer inspection of this system may reveal important clues as to the linguistic reliability of the Proceedings. I will start with a brief characterization of the script and then focus on the implications for the rendering of spoken language in the Proceedings.

3.2.2.1 Gurney’s shorthand: an overview

Gurney's (1752: 3) avowed objective was to enable the shorthand writer 'to take a Speech, or Sermon verbatim, as a Person talks in common'. His script consists of an 'alphabet' of invented symbols for consonants and vowels but has some characteristics of a consonantal writing system in that vowels can be left out. For example, he transcribes <lmntsn> 'lamentation' or <msngr> 'messenger' (p. 11). In spite of this, vowels are often indicated by diacritics (through dots or the vertical position of the following consonant). High-frequency words 'such as Prepositions, & terminations' are represented by 'arbitrary Characters' (3). These logographic elements are mostly derived from symbols of the basic alphabet and extended iconically (e.g.  'little' vs. 'little' vs.  'large', both from the symbol 'large', both from the symbol  for l, p. 12) and can represent several words (for instance a dot. can mean 'they, thee, the, thy, of', p. 14). In principle, however, Gurney's shorthand follows conventional orthography, as illustrated by his transcription of loan, which indicates both <o> and <a> (p. 13): for l, p. 12) and can represent several words (for instance a dot. can mean 'they, thee, the, thy, of', p. 14). In principle, however, Gurney's shorthand follows conventional orthography, as illustrated by his transcription of loan, which indicates both <o> and <a> (p. 13):

|

|

'loan' |

l.o.an |

However, the script also has some phonological traits in that e.g. <gh> in brought is omitted (p. 13):

|

|

'brought' |

br.ot |

In a similar manner, law is rendered as  ˙ (l-a, p. 27). ˙ (l-a, p. 27).

The following example illustrates the phonological principle in that the <e> in single and line is omitted. It also contains orthographic elements in that (1) – stands for <in> and thus represents both [In] (in single) and [aIn] (in line) and (2) the velar nasal in single is expressed by two symbols, – and  . [5] . [5]

|

|

'single line' |

s.in.g.ll.in |

I will now consider some implications of Gurney's stenographic script for the faithfulness of his trial transcripts. As mentioned before, this is meant as a first approach to the problem, not as an exhaustive analysis.

3.2.2.2 Capturing morpho-syntax through shorthand

The symbols introduced in Gurney's chapter on 'Persons Moods & Tenses' (19-22) do not distinguish between inflected and uninflected auxiliaries ( stands for 'may' or 'mayst', stands for 'may' or 'mayst',  for 'can' or 'canst', for 'can' or 'canst',  for 'should' or 'shouldst', etc., p. 18-20). One could argue that this renders the Proceedings less reliable as far as the inflection of verbs in the 2sg present tense is concerned, but apart from the fact that the context would disambiguate the possible readings (you may but thou mayst), we know that by 1700 thou and the appropriate -est inflection had undergone functional contraction and were largely restricted to dialects, biblical and archaic language, and the speech of Quakers (Görlach 1991: 85, 88). [6] However, even if 2sg verbal inflection is only marginally relevant in the 18th century, the foregoing is an indication that even shorthand could not have been absolutely accurate in the recording of details like inflections. A further example is provided by the symbol for the indefinite article, a dot placed on the top left of the noun phrase, which stands for the two allomorphs a and an (p. 16). A study on variation in this area (e.g. a ~ an before nouns starting h-) has to proceed very carefully indeed since the shorthand manuscript would not have distinguished between a and an, using a simple dot in both cases. Only when expanding his shorthand notes for the typesetter would the scribe choose a particular allomorph. That is, the form of the indefinite article that we find on the printed page of the Proceedings depended for a good part on the scribe's memory. With high-frequency items like inflections or articles it is very unlikely that the scribe would have remembered the exact variant used in every single instance, not even after only a couple of hours. for 'should' or 'shouldst', etc., p. 18-20). One could argue that this renders the Proceedings less reliable as far as the inflection of verbs in the 2sg present tense is concerned, but apart from the fact that the context would disambiguate the possible readings (you may but thou mayst), we know that by 1700 thou and the appropriate -est inflection had undergone functional contraction and were largely restricted to dialects, biblical and archaic language, and the speech of Quakers (Görlach 1991: 85, 88). [6] However, even if 2sg verbal inflection is only marginally relevant in the 18th century, the foregoing is an indication that even shorthand could not have been absolutely accurate in the recording of details like inflections. A further example is provided by the symbol for the indefinite article, a dot placed on the top left of the noun phrase, which stands for the two allomorphs a and an (p. 16). A study on variation in this area (e.g. a ~ an before nouns starting h-) has to proceed very carefully indeed since the shorthand manuscript would not have distinguished between a and an, using a simple dot in both cases. Only when expanding his shorthand notes for the typesetter would the scribe choose a particular allomorph. That is, the form of the indefinite article that we find on the printed page of the Proceedings depended for a good part on the scribe's memory. With high-frequency items like inflections or articles it is very unlikely that the scribe would have remembered the exact variant used in every single instance, not even after only a couple of hours.

This is a rather sobering finding, given that shorthand-based recordings of spoken language have so far been accepted as relatively faithful in the literature (see above). Nevertheless, Gurney's brachygraphy does record other details, including features of spoken language like auxiliary contractions:  'you will' (you w-il) vs. 'you will' (you w-il) vs.  'you'll' (you-l, p. 27). But even here are difficulties, e.g. when we turn to proclitic 't (< it): Gurney's shorthand representation of 'twill (< it will) is ambiguous since the symbol for t is also used as an abbreviation for it (p. 11): Gurney transcribes orthographic 'twill ׀ 'you'll' (you-l, p. 27). But even here are difficulties, e.g. when we turn to proclitic 't (< it): Gurney's shorthand representation of 'twill (< it will) is ambiguous since the symbol for t is also used as an abbreviation for it (p. 11): Gurney transcribes orthographic 'twill ׀  (p. 26-27), with a space between t/it and will (similarly 'tmay ׀ (p. 26-27), with a space between t/it and will (similarly 'tmay ׀  ˙). Because of this space there is no way of knowing, on the basis of the shorthand manuscript alone, whether ׀ represents the full form it or proclitic 't. ˙). Because of this space there is no way of knowing, on the basis of the shorthand manuscript alone, whether ׀ represents the full form it or proclitic 't.

The foregoing remarks demonstrate the need for a study establishing whether results based on an analysis of features that can be unambiguously encoded in the shorthand script (e.g. contraction of will/shall) are more reliable than results based on features where the shorthand system is ambiguous (e.g. it ~ 't). In any case, linguists analyzing spoken language recorded in stenographic writing will do well by familiarizing themselves with shorthand practices of the period to assess the reliability of their material.

Unfortunately, the examples in Gurney's manual do not contain instances of negative contractions like can't or doesn't, the feature analyzed in the following sections. Gurney's chapter on 'The Negative not ¬ ' (p. 23) only transcribes the expanded forms would not, cannot, shall not, must not, might not, may not, ought not, and was not. Therefore, although it is theoretically possible to represent negative contractions in Gurney's system, it is impossible to say whether Gurney would have differentiated between cannot and can't, etc. This can only be checked by comparing an original shorthand manuscript with the printed version of the Proceedings, but so far, such manuscripts have not come to light (Tim Hitchcock, p.c. 2007-02-20).

What we do have, however, is interesting evidence concerning the working methods of the scribes in the trial accounts themselves. In the second trial of Elizabeth Canning, Thomas Gurney was asked to report to the court what he had taken down during the first trial. [7] The attorney then proceeded:

Mr. Davy. As far as you have mentioned, are you able to say upon your oath, that that was the evidence that the girl upon her oath then gave in court?

Gurney. The substance of it is the evidence she gave in court.

Note Gurney's use of 'substance' rather than something like 'her very words' (cf. also 17560528-45). Later in the trial, Gurney was asked to compare the testimony of Elizabeth Canning’s mother with what she had said in the first trial:

Mr. Davy to Thomas Gurney. You hear the evidence this woman has given; look at your minutes, and give an account of what she said in her evidence on that trial, as to the state and condition in which her daughter came home, and particularly how she was dress'd.

[Gurney cites the evidence]

Mr. Davy. Were these her own words?

Gurney. I have here mentioned the person she where she said I. I will not take upon me to say these are the very words she made use of, or that she made use of no more words; it is my method, if a question brings out an imperfect answer, and is oblig'd to be ask'd over again, and the answer comes more strong, I take that down as the proper evidence, and neglect the other; […] It is not to be expected I should write every unintelligible word that is said by the evidence. (The Trial of Elizabeth Canning, 1754, pp. 19-20, 104)

Again, Gurney made it clear that while he strove to be faithful to the spoken word, this was not always possible or even desirable (on the role of the scribe, cf. also Shoemaker forthcoming). In a 1758 trial, he was asked to recount the statement of a foreigner, which he did in Standard English, adding that 'I took that to be his meaning which I have printed, he speaking as most of the foreign Jews do, a sort of broken English', making it clear that there was a linguistic difference between the actual speech act and its representation in the Proceedings (17580113-30).

3.2.3 Comparison of a trial in the Proceedings with an alternative account

The left column of the text in Appendix A shows an extract from the trial of John Ayliffe, 17591024-27, and an alternative account of the same trial, entitled The tryal at large of John Ayliffe (henceforth referred to as Tryal) in the right column. [8] One can see at first glance that the account in the Proceedings is considerably shorter than the alternative Tryal (718 as opposed to 1,290 words). It is interesting that both versions were 'Printed, and sold by M. Cooper at the Globe in Pater-noster-Row', so one would suppose that Cooper would either have produced a longer and a condensed version from the same manuscript or produced the longer Tryal first and abridged it for inclusion in the Old Bailey Proceedings. However, things are not that straightforward. There is some of overlap between the two versions, as in e.g. lines 3, 30, 52:

|

Proceedings |

Tryal |

| 3 |

Thomas. I am clerk to Mr Jones, a Stationer in the Temple. |

Henry Thomas. I am clerk to Mr Jones, a Stationer, in the Temple. |

| 30 |

Prisoner. I should be glad to look at that deed. |

Prisoner. I should be glad to look at that deed. |

| 52 |

Hargrave. It is: I saw Mr Ayliffe sign this receipt for 1700 l. |

Walter Hargrave. It is: I saw Mr Ayliffe sign this receipt for 1700 l. |

Sometimes the Proceedings simply omit some text of the longer version, either complete speech acts as in lines 21 or 42:

|

Proceedings |

Tryal |

| 21 |

|

John Fannen. I am not sure; but to the best of my remembrance, it was sometime the beginning of December last, at Mr Fox's house. |

| 42 |

|

Lord Chief Justice. Let it be read. |

or parts of a speech act, e.g. line 48:

|

Proceedings |

Tryal |

| 48 |

Hargrave. By Mr Ayliffe: I saw him seal and deliver it. |

Walter Hargrave. By Mr Ayliffe. – I saw him sign, seal, and deliver it, as his act and deed. |

But there are also more serious differences between the two versions:

- The Proceedings contain material not found in Tryal:

|

Proceedings |

Tryal |

| 19 |

Fannen. This deed (taking the counterpart in his hand) was executed by Mr Ayliffe in my presence. |

John Fannen. This deed was executed by Mr Ayliffe in my presence. |

|

Proceedings |

Tryal |

| 60 |

Hargrave. Because he said he was not willing Mr Fox should know of it? |

Walter Hargrave. The reason Mr Ayliffe gave, was, that he would not on any account have it come to Mr Fox's ears. |

- Lexical differences, e.g. positively > particularly, leave out > leave a blank:

|

Proceedings |

Tryal |

| 7 |

Thomas. I can't particularly say that; sometimes we leave a blank by the gentlemens desire, perhaps they may add another covenant, or something of that sort, I can't recollect the reason for that. |

Henry Thomas. I cannot positively say. –

We sometimes leave out the conclusion by gentlemen's desire, in order that they may add a covenant, or some such thing, if it should be thought necessary; but I cannot particularly recollect the reason why the conclusion was omitted in this case. |

- Differences in morphology and syntax (e.g. sometimes we leave vs. we sometimes leave line 7, can't vs. cannot, was you? vs. Are you? line 24, two sentences in Tryal fused into one, line 55):

|

Proceedings |

Tryal |

| 7 |

Thomas. I can't particularly say that; sometimes we leave a blank by the gentlemens desire, perhaps they may add another covenant, or something of that sort, I can't recollect the reason for that. |

Henry Thomas. I cannot positively say. –

We sometimes leave out the conclusion by gentlemen's desire, in order that they may add a covenant, or some such thing, if it should be thought necessary; but I cannot particularly recollect the reason why the conclusion was omitted in this case. |

| 24 |

Q. Was you a subscribing witness to this deed? |

Mr Wedderburne. Look upon the back of this deed; are you one of the subscribing witnesses? |

| 55 |

Q. Do you remember any request being made, and by whom, to keep this mortgage a secret? |

Mr Aston. Do you remember any request being made at this time, to keep the mortgage of that lease a secret? and if you do, tell us by whom such request was made, and who were present. |

The last point in particular casts doubt on Kytö & Walker's (2003: 234) statement that '[w]hat a 'faithful' or 'verbatim' record is generally expected to convey, to a large extent, is the lexical items and grammatical structures'. The differences between the two versions suggest that they come from two different scribes rather than being an abridged and an expanded version based on the same manuscript. What this shows us yet again is that the Proceedings (just like other early trial accounts) cannot naïvely be taken to contain truly verbatim accounts of the trials at the Old Bailey, even though they were taken down in shorthand. At the same time, however, they are not automatically less reliable than other accounts.

3.3 Testing the reliability of the Old Bailey Corpus: a quantitative analysis of negative contraction

In the following I will test the reliability of the Proceedings as a source of spoken language on the basis of the variation between contracted and uncontracted forms of negated auxiliaries, such as do not vs. don't.

The choice of negative contraction as a diagnostic feature for the linguistic reliability of a text representing speech is motivated by the fact that negative contraction is an established characteristic of present-day spoken language (Greenbaum & Nelson 2002: 211; Mazzon 2004: 105), including legal English. For example, in the 13 courtroom texts of spoken English (127,474 words) included in the web-version of the British National Corpus, contracted forms account for 72.4% of all negated auxiliaries (807/1,115), while in the corresponding written category (non-academic political, legal and educational texts; 4,477,831 words in 93 texts) they make up just 15.3% (1,808/11,852), and many of these actually occur in quotes of spoken language. [9] Given the tendency of contracted forms to predominate in today's spoken English, we proceed on the hypothesis that negative contraction is more frequent in the spoken passages than in the prose text of the Proceedings.

Tables 3 to 6 show the distribution by decade of contracted and uncontracted negation involving auxiliaries in the prose and speech passages of the Old Bailey Corpus (OBC) from 1732 to 1834. [10] The tables subsume orthographical variants under the forms indicated in the first column. Thus haven't includes haven't, ha'n't, han't, and so on. Tables 3 and 4 are based on the speech passages, Table 5 on the prose passages, and Table 6 presents a summary:

Table 3. Negative contraction in the Old Bailey Corpus, speech only.

| Auxiliary |

1732- |

1740- |

1750- |

1760- |

1770- |

1780- |

1790- |

1800- |

1810- |

1820- |

1830- |

Total |

aren't |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

15 |

can't |

625 |

1081 |

1209 |

450 |

323 |

202 |

26 |

38 |

217 |

130 |

146 |

4447 |

don't |

962 |

1043 |

1530 |

738 |

1478 |

710 |

4115 |

1314 |

789 |

1161 |

1388 |

15228 |

haven't |

12 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

22 |

shan't |

25 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

6 |

32 |

35 |

109 |

won't |

147 |

54 |

3 |

2 |

27 |

13 |

42 |

48 |

33 |

168 |

115 |

652 |

Total |

1767 |

2189 |

2743 |

1191 |

1831 |

927 |

4183 |

1414 |

1048 |

1492 |

1684 |

20467 |

Table 4. Uncontracted negation in the Old Bailey Corpus, speech only.

| Auxiliary |

1732- |

1740- |

1750- |

1760- |

1770- |

1780- |

1790- |

1800- |

1810- |

1820- |

1830- |

Total |

| are not |

81 |

133 |

139 |

166 |

245 |

715 |

600 |

423 |

286 |

570 |

422 |

3780 |

| cannot [11] |

271 |

1035 |

911 |

1718 |

2139 |

7983 |

6984 |

4698 |

2393 |

4959 |

4282 |

37373 |

| could not |

716 |

1378 |

1450 |

1779 |

1861 |

4038 |

3750 |

3093 |

3162 |

5548 |

3801 |

30576 |

| dare not |

3 |

4 |

10 |

12 |

7 |

24 |

8 |

7 |

11 |

20 |

15 |

121 |

| did not |

2049 |

4505 |

5075 |

5483 |

6660 |

16922 |

16246 |

12063 |

10771 |

23109 |

18396 |

121279 |

| do not |

72 |

709 |

782 |

1717 |

1386 |

8941 |

4364 |

4133 |

3224 |

7081 |

5697 |

38106 |

| does not |

32 |

133 |

100 |

102 |

113 |

715 |

512 |

259 |

216 |

409 |

264 |

2855 |

| had not |

420 |

749 |

910 |

1201 |

1209 |

2732 |

2933 |

2587 |

2528 |

5137 |

4193 |

24599 |

| has not |

48 |

95 |

95 |

82 |

85 |

360 |

276 |

198 |

136 |

417 |

392 |

2184 |

| have not |

115 |

267 |

340 |

318 |

324 |

1311 |

1304 |

869 |

682 |

2019 |

1780 |

9329 |

| is not |

164 |

478 |

550 |

579 |

679 |

2857 |

2248 |

1432 |

1256 |

2384 |

1811 |

14438 |

| may not |

8 |

21 |

20 |

18 |

22 |

104 |

90 |

33 |

13 |

21 |

21 |

371 |

| might not |

53 |

77 |

73 |

70 |

89 |

285 |

227 |

168 |

120 |

189 |

153 |

1504 |

| must not |

31 |

40 |

35 |

38 |

59 |

158 |

153 |

103 |

72 |

69 |

36 |

794 |

| need not |

36 |

44 |

55 |

54 |

72 |

166 |

85 |

76 |

62 |

126 |

88 |

864 |

| ought not |

7 |

14 |

2 |

11 |

26 |

74 |

54 |

36 |

24 |

30 |

43 |

321 |

| shall not |

25 |

66 |

68 |

120 |

96 |

286 |

190 |

116 |

85 |

132 |

101 |

1285 |

| should not |

117 |

253 |

267 |

368 |

373 |

924 |

782 |

634 |

540 |

1050 |

822 |

6130 |

| will not |

53 |

209 |

281 |

335 |

282 |

1104 |

819 |

439 |

343 |

712 |

570 |

5147 |

| would not |

693 |

1382 |

1313 |

1574 |

1488 |

2911 |

2636 |

2039 |

1810 |

3088 |

2210 |

21144 |

| Total |

4301 |

10210 |

11163 |

14171 |

15727 |

49699 |

41625 |

31367 |

25924 |

53982 |

42887 |

301056 |

Table 5. Uncontracted negation in the Old Bailey Corpus, prose only.

| Auxiliary |

1732- |

1740- |

1750- |

1760- |

1770- |

1780- |

1790- |

1800- |

1810- |

1820- |

1830- |

Total |

| are not |

1 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

16 |

11 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

43 |

| cannot |

3 |

18 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

38 |

18 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

100 |

| could not |

52 |

120 |

86 |

86 |

103 |

91 |

40 |

26 |

26 |

56 |

21 |

707 |

| did not |

69 |

154 |

190 |

209 |

400 |

302 |

187 |

250 |

94 |

487 |

178 |

2520 |

| do not |

0 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

8 |

6 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

24 |

| does not |

6 |

18 |

6 |

9 |

13 |

34 |

24 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

1 |

127 |

| had not |

25 |

51 |

26 |

23 |

41 |

39 |

18 |

25 |

11 |

41 |

32 |

332 |

| has not |

1 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

9 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

42 |

| have not |

0 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

15 |

| is not |

7 |

34 |

11 |

8 |

24 |

59 |

40 |

12 |

15 |

14 |

3 |

227 |

| may not |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| might not |

7 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

| must not |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

12 |

| need not |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| ought not |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

19 |

| shall not |

0 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

| should not |

16 |

17 |

5 |

12 |

12 |

11 |

9 |

3 |

0 |

10 |

4 |

99 |

| was not |

55 |

166 |

95 |

70 |

217 |

226 |

88 |

97 |

115 |

84 |

40 |

1253 |

| will not |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

24 |

| would not |

29 |

44 |

30 |

16 |

46 |

38 |

16 |

14 |

15 |

20 |

7 |

275 |

| Total |

276 |

658 |

466 |

446 |

886 |

889 |

490 |

450 |

291 |

730 |

288 |

5870 |

Table 6. Summary of negative contraction in the Old Bailey Corpus (p ≤ 0.001).

|

Speech |

Prose |

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

Contracted |

20473 |

6.4 |

5 |

0.1 |

Uncontracted |

301056 |

93.6 |

5870 |

99.9 |

In the spoken passages from 1732 to 1834, there are over 20,000 instances of contracted auxiliaries, in other words, 6.4% of all negated auxiliaries show contracted n't in the speech passages. Most of the tokens are accounted for by don't, can't, and won't (there are only 18 tokens of aren't, haven't is represented with only 22 tokens, and shan't is found only 109 times). By contrast, in the prose passages of the same period there are only five contracted forms in total, less than 0.1% of all negated auxiliaries. [12]

The first solid conclusion we can draw from this is that there is a significant difference in the distribution of contracted and uncontracted negative auxiliaries in the OBC, with the former being almost exclusively confined to spoken language. The corpus therefore reflects the characteristics of spoken language, but it remains to be shown in how far this distributional pattern mirrors the actual spoken language of the period. In comparison to the BNC's 72.4% contraction rate in spoken legal English, the Old Bailey's 6.4% seem rather low. Several factors can account for this discrepancy:

- Overall language change. Contraction may simply have been less frequent in the 18th and 19th centuries (overall and with regard to the cliticization of n't to individual auxiliaries).

- Genre change. Generic conventions (broadly written vs. spoken) may have made it more difficult for contracted negators to appear in written genres than today.

- Register change. There may have been a change in the linguistic choices in the legal register, with negative contraction felt to be more colloquial than today and thus inappropriate for a formal legal register, even when spoken.

- The scribal filter effect mentioned above.

To test whether the seemingly low ratio of negative contraction in the OBC results from its possibly unfaithful representation of the characteristics of spoken language, I will first compare the picture we find in the Proceedings with what we know about the general development of negative contraction in the history of English. Contraction of not emerged in the 17th century, maybe as early as 1600 in speech and in the second half of the century in writing (Barber 1997: 180; Brainerd 1989; Strang 1970: 151; Warner 1993: 208). Lass (1999: 180) notes that '[c]litic spellings are uncommon until the 1660s; they are frequent in Restoration comedy, and by the early eighteenth century seem to be the norm in speech'. It is not clear on what evidence Lass bases this last claim, but given that negative contraction got more common in writing only towards the end of the 17th century, the situation presented by the Proceedings does not seem too far off the mark.

3.3.1 External fit

A clearer picture is afforded by comparing negative contraction in the OBC with that in another corpus of spoken English, the Corpus of English Dialogues 1560-1760 (CED). The CED includes five genres, trials, witness depositions, drama comedy, didactic works, and prose fiction (for a full documentation of the CED see Kytö & Walker 2006). Table 7 shows negative contraction in the CED trial texts from 1560 to 1760. [13] For comparison, the table also includes n't -forms in the OBC for the period of overlap with the CED, 1732-1759.

Table 7. Negative contraction in CED trials 1560-1760 and Old Bailey Proceedings 1732-59.

| |

Corpus of English Dialogues (N = 1147) |

Old Bailey |

|

1560-99 |

1600-39 |

1640-79 |

1680-1719 |

1720-60 |

1732-59 |

Auxiliary |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

can't |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

4.2 |

169 |

68.4 |

60 |

44.1 |

2915 |

56.8 |

cannot |

7 |

|

13 |

|

138 |

|

78 |

|

76 |

|

2217 |

|

don't |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

5.6 |

101 |

51.5 |

82 |

63.6 |

3535 |

69.3 |

do not |

6 |

|

23 |

|

85 |

|

95 |

|

47 |

|

1563 |

|

shan't |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

14.3 |

0 |

0 |

23 |

12.6 |

shall not |

1 |

|

100 |

|

19 |

|

6 |

|

3 |

|

159 |

|

won't |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

26.2 |

3 |

21.4 |

204 |

27.3 |

will not |

7 |

|

13 |

|

49 |

|

31 |

|

11 |

|

543 |

|

The CED corroborates the claim in the literature that negative contraction started in the first half of the 17th century but became frequent only in the last decades of that century. Comparing the last sub-period of the CED (1720-1760) with the first sub-period of the OBC considered here (1732-1759), a Chi-square test shows a significant difference only for can't/cannot (p ≤ 0.01). The differences involving the other auxiliaries are not significant (don't/do not: p ≤ 0.2, shan't/shall not: p ≤ 1, won't/will not: p ≤ 1). In other words, for the period of overlap, the rate of negative contraction is rather similar in the two corpora. Even for the significant difference with regard to can't, there is only a 12.7% gap between the CED and the OBC. There are two further parallels: (1) both corpora show an absence of negative contraction with past forms of auxiliaries, [14] and (2) for the period of overlap, the OBC shows negative contraction with the same auxiliaries that attract n't in the CED. [15] Thus, at least as far as the period of overlap is concerned, the distribution of contracted vs. uncontracted negatives in the speech passages of the OBC is similar to that of a sampled corpus, the CED. The OBC can therefore be taken to be just as representative of spoken language as other trial texts.

The comparatively low rate of 6.4% negative contraction in the OBC is due to several factors: first of all, negative contraction is only attested with non-past auxiliary forms, while the percentage was calculated on the basis of non-past and past expanded forms. Secondly, in the OBC, n't attaches only to six auxiliaries and not to the others (n't has a larger range today). If one factors out past forms and those auxiliaries that do not attract enclitic negatives, then the picture looks more familiar from the perspective of present-day English (though still not identical, which one would not expect it to be, given the time difference of ±200 years). Note that a strictly formal approach has been taken in Table 8: starting form negative contraction, only those uncontracted auxiliary forms are included that match the contracted counterpart.

Therefore, since be shows negative contraction only in the form aren't (there are no tokens of isn't), the figures for e.g. uncontracted are not exclude am not, is not, was not, and were not. Similarly, do not excludes does not and did not, and have not excludes has not and had not:

Table 8. Negative contraction and uncontracted forms in the Old Bailey Corpus, speech only.

Auxiliary |

1732- |

1740- |

1750- |

1760- |

1770- |

1780- |

1790- |

1800- |

1810- |

1820- |

1830- |

aren't |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

are not |

81 |

133 |

139 |

166 |

245 |

715 |

600 |

423 |

286 |

570 |

422 |

can't |

625 |

1081 |

1209 |

450 |

323 |

202 |

26 |

38 |

217 |

130 |

146 |

cannot |

271 |

1035 |

911 |

1718 |

2139 |

7983 |

6984 |

4698 |

2393 |

4959 |

4282 |

don't |

962 |

1043 |

1530 |

738 |

1478 |

710 |

4115 |

1314 |

789 |

1161 |

1388 |

do not |

72 |

709 |

782 |

1717 |

1386 |

8941 |

4364 |

4133 |

3224 |

7081 |

5697 |

haven't |

12 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

have not |

115 |

267 |

340 |

318 |

324 |

1311 |

1304 |

869 |

682 |

2019 |

1780 |

shan't |

25 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

6 |

32 |

35 |

shall not |

25 |

66 |

68 |

120 |

96 |

286 |

190 |

116 |

85 |

132 |

101 |

won't |

147 |

54 |

3 |

2 |

27 |

13 |

42 |

48 |

33 |

168 |

115 |

will not |

53 |

209 |

281 |

335 |

282 |

1104 |

819 |

439 |

343 |

712 |

570 |

Figure 6 is based on Table 8 and shows the percentage of the contracted negatives can't, don't, ha'n't, shan't, won't, and aren't vs. their uncontracted counterparts in the speech passages.

Figure 6. Percentage of negative contraction for six auxiliaries in the Old Bailey Corpus.

In comparison to the overall figure of 6.4% the figure shows a considerably higher percentage of negative contraction when only the six affected auxiliaries are considered, as can easily be seen from the average (dotted line). Do not even shows a contraction rate of 93% in the 1730s, though this admittedly is an extreme case. Nevertheless, there is also a noticeable overall drop in negative contraction over the 100 years considered here, from an average of 74% in the 1730s to as low as 12% in the 1830s. This is rather surprising, since one would have expected a steady rise, given that negative contraction is so common today. It could mean that the early Proceedings are more representative of spoken language, possibly because the language became more and more formal as the City of London gained control over the publication and it became an official document (see Section 2). Further studies will have to show whether other corpora show a similar kind of behaviour with regard to negative contraction in the 18th century.

The decline in negative contraction may also be a function of the increasing control that the City authorities exerted over the Proceedings in the course of the 18th century. Robert Shoemaker (p.c. 2007-05-20) suggests that 'the character and audience of the Proceedings changed significantly between 1720 and 1778, when they entered the period of close City control. As they became longer and more expensive during this period, the language became more respectable'.

3.3.2 Internal consistency

Figure 6 shows a strong fluctuation of contraction rates, especially as far as don't is concerned. To a certain degree this is the result of the small intervals chosen here (decades), but there may also be other reasons: as mentioned before (Section 4), there are several layers of filters that stand between the speech event at the Old Bailey and the linguist trying to reconstruct the spoken language of the period. These are the filters imposed by the scribes, by the proofreaders, the typesetters and printers, and by the publishers. It is to the influence of these persons that I will turn in the following. From the late 1730s, the title pages of the Proceedings regularly mention the scribe and/or printer. [16] Table 9 gives an overview of this information:

Table 9. Scribes and printers in the Proceedings, as indicated on the title pages.

From |

to |

Scribe |

Printer |

16781211 |

|

|

G. Hills |

16920406 |

|

|

Thomas Braddyl |

17261207 |

|

|

J. Read |

17381206 |

17401015 |

|

T. Cooper |

17410405 |

17411014 |

|

J. Roberts |

17411204 |

17420603 |

|

T. Payne |

17420714 |

17430114 |

|

T. Cooper |

17430223 |

17451016 |

|

M. Cooper |

17451204 |

17460117 |

|

C. Nutt |

17471209 |

17481207 |

|

M. Cooper |

17490113 |

17551022 |

Thomas Gurney |

M. Cooper |

17551204 |

17571026 |

Thomas Gurney |

J. Robinson |

17571207 |

17591024 |

Thomas Gurney |

M. Cooper |

17591205 |

17601022 |

Thomas Gurney |

G. Kearsley |

17601204 |

17611021 |

Thomas Gurney |

J. Scott |

17730707 |

17750712 |

Joseph Gurney |

|

17751206 |

17771015 |

Joseph Gurney |

William Richardson |

17771203 |

17811017 |

Joseph Gurney |

|

17811205 |

17820410 |

William Blanchard |

|

17820515 |

17820703 |

Joseph Gurney |

|

17820911 |

17921031 |

E. Hodgson |

|

17921215 |

17951028 |

Manoah Sibly |

Henry Fenwick |

17951202 |

17970215 |

Marsom & Ramsey |

W. Wilson |

17970426 |

18011028 |

William Ramsey |

W. Wilson |

18011202 |

18051030 |

Ramsey & Blanchard |

W. Wilson |

18051204 |

18150510 |

Job Sibly |

R. Butters |

18150621 |

18160918 |

J.A. Dowling |

R. Butters |

18161204 |

18280110 |

Henry Buckler |

T. Booth |

18280221 |

18300415 |

Henry Buckler |

Henry Stokes |

18300527 |

18310512 |

Henry Buckler |

Henry Stokes & George Titterton |

18310630 |

18330411 |

Henry Buckler |

George Titterton |

18330516 |

18331128 |

Henry Buckler |

William Johnston |

18340102 |

18341016 |

Henry Buckler |

William Tyler |

Joseph Gurney is the first scribe to be mentioned in the Proceedings, on the title page of 17730908, but we know that his father had been taking shorthand notes of the sessions since at least 1749, when his name first appears in an advertisement at the end of the Proceedings: 'SHORT-HAND Taught in an easy and expeditious Method, by Thomas Gurney, the Writer of these Proceedings' (17490113, my emphasis). Similar advertisements appeared in 129 further issues, so Thomas Gurney was responsible for recording the trials from the mid-18th century onwards. After his death in 1770, his bookbinder son Joseph took over the business of recording and publishing the Proceedings (see the advertisement in 17700711: 'By the late Mr. THOMAS GURNEY, upwards of Twenty Years Writer of these PROCEEDINGS'). For 85 years, therefore, we know who the scribes were and, for an even longer period, who printed the Proceedings. [17]

3.3.2.1 Micro-study of the scribes

With this information we can now proceed to a micro-study of the material in the OBC in order to establish whether there is a significant correlation between the scribes/printers and the linguistic detail captured in the Proceedings. Perhaps the most noticeable fluctuation in the development of negative contraction shown in Figure 6 is the sudden drop of contraction from an average of 29% in the 1770s to a mere 4% in the 1780s, only to rise again to 23% in the 1790s. This could be an indication of an internal inconsistency of the corpus and will therefore be the focus of the first case study. Table 10 splits the Proceedings in the 1780s up by scribe and indicates the respective figures for negative contraction:

Table 10. Negative contraction in speech, in the 1780s, by scribe.

|

Gurney I

17800112- |

Blanchard

17811205- |

Gurney II

17820515- |

Hodgson

17820911- |

can't |

78 |

39 |

14 |

71 |

cannot |

725 |

181 |

47 |

7030 |

don't |

211 |

163 |

35 |

301 |

do not |

919 |

83 |

50 |

8604 |

shan't |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

shall not |

24 |

6 |

4 |

252 |

won't |

5 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

will not |

107 |

34 |

6 |

957 |

Joseph Gurney took down 15 proceedings from January 1780 to November 1781 and 3 proceedings from May 1782 to July 1782. The four sessions from December 1781 to April were transcribed by William Blanchard. However, E. Hodgson was the scribe who was responsible for the bulk of the Proceedings in the 1780s, 67 in all. For the present purposes we will have to assume that apart from the change in the person of the scribe all other parameters remain equal, i.e. we will idealize and assume that there is no significant language change within one decade and that the sociobiographical composition of the trial participants remained the same throughout. Figures 7 and 8 chart the percentages of negative contraction for can't and don't:

Figure 7. Negative contraction of can not, in the 1780s, by scribe.

Overall distribution: p ≤ 0.001. The difference B↔GII is not significant (p ≤ 1). The difference GI↔GII is significant (p ≤ 0.01). The differences between all other pairs are highly significant (p ≤ 0.001).

Figure 8. Negative contraction of do not, in the 1780s, by scribe.

Overall distribution: p ≤ 0.001. The differences between all pairs are highly significant (p ≤ 0.001).

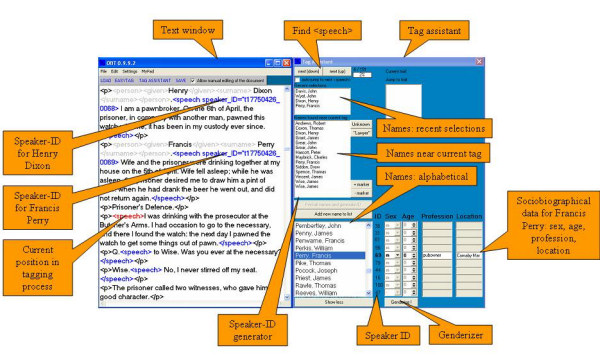

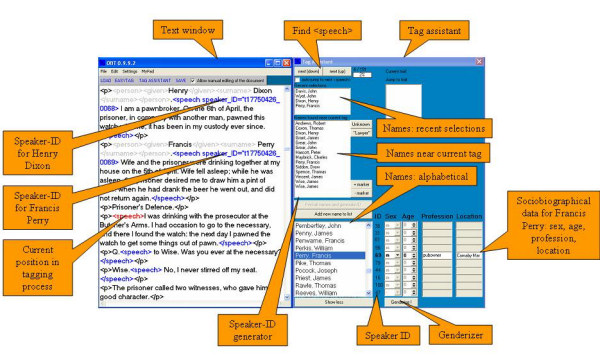

Chi square tests show that, except for Blanchard↔Gurney II in Figure 7, all differences in the rate of negative contraction between the scribes are significant. The first finding is that there is a much lower rate of negative contraction in Hodgson's Proceedings than in those of Gurney and Blanchard in the 1780s. Averaging Gurney and Blanchard and setting them against Hodgson yields the following picture: