A cognitive approach to opposites: The case of Swedish levande 'alive' and död 'dead'

Anna Vogel, University of Stockholm

In the present paper, opposites are examined and discussed, and a way of describing them from a cognitive perspective is suggested. Related research disagrees upon whether opposites are symmetrical, and whether concepts should be integrated in the relation of opposites. The Swedish opposites levande 'alive' and död 'dead' have been studied thoroughly in order to provide empirical data. Arguments are presented in favour of an analysis in which opposites show semantic symmetry to some extent. When it comes to distribution and domains, however, opposites do not show symmetry. Further, it is argued that concepts should be included in the relation of opposites. The asymmetries found are related to markedness, information value, Aktionsart and the prototype of the word connected to referent of the subject/NP that one of the opposites describes.

Opposite terms and the nature of opposites intrigue and fascinate. Myths have it that opposites are both far apart and close, like the allegedly thin line between madness and genius. Untrained native speakers have clear intuitions about the overall category of opposites (Cruse 1994:178). The opposites in language supposedly reflect a human cognitive tendency to categorise experiences with the help of dichotomous relations (Lyons 1977:277). Terms of oppositeness incorporate both closeness and distance. The distance reflects only one semantic dimension. The closeness, on the other hand, includes syntactic distribution, which is supposed to be identical, as well as contextual factors (Cruse 1986:197, Pohl 1970:188). The present paper aims to explore the nature of opposites in terms of symmetry, similarity and difference, and suggest how this can be undertaken within a cognitive semantic framework.

In the article, Swedish levande - död 'alive - dead' is examined. The alleged symmetry/closeness is in focus. Are the two words semantically symmetrical, i.e., do they differ in only one dimension? What does their use look like and how do language users understand them?

As Lehrer & Lehrer (1982) points out, the terminology concerning opposites suffers from some confusion. The present paper follows Lyons (1977:279), which uses opposition to describe dichotomous contrast. The term antonymy is reserved for gradable opposites (e.g. high - low), while complementarity denotes ungradable opposites (e.g. dead - alive). However, complementaries can appear in a gradable context, such as "Is John dead?" "No, he is very much alive". This fact is discussed in several studies; see for example Cruse (1980), Jackson (1988), Jones (2002), Murphy (2003), and Paradis & Willners (2006).

Willners (2001) declares that the words in an antonymous pair must be similar in all respects but one. This is in accordance with Cruse (1986) who writes that opposites typically differ along only one dimension of meaning. In respect of all other features they are identical, and thus show almost identical distributions.

Justeson & Katz suggest that "adjectives may be more or less antonymous rather than simply antonymous or not antonymous" (1992:182). Muehleisen (1997:4) writes that good opposites have "the clang", which means that language users identify two words as opposites: this is the case with hot - cold, but not with loud - faint. Further, good opposites should also be associated with the same kind of nouns (things) (1997:113).

A main issue in the related research on opposites concerns what is included in the relation of opposition. Some studies on opposition and antonymy regard concept(s) as constituting the sense of a word (Nowak 2006 and Cruse 1992), and as such, concepts must be incorporated into the relation of oppositeness. Other studies view concepts as separated from the sense (Miller et al. 1990, Gross & Miller 1990, and Murphy 2003) and thus, they are not part of the relation of oppositeness. Fellbaum (1995) does not overtly commit to either side, but presents arguments that opposition (in her case, antonymy) is a relation between concepts, pointing out that antonymy can exist between words belonging to different word classes. Nowak agrees with her, and argues that the grammatical category of difference, between for example dead (adjective) and dead (noun), consists of different profiling. The conceptualiser chooses to adopt a certain profiling for a given conceptual content.

Krishnamurty (2002) shows that the two words of an antonymous pair exhibit differences in their collocational profile, and thus do not have identical distribution. Murphy (2003) sheds further light on the distribution of opposites. She indicates some antonyms that do not exhibit symmetrical distribution in linguistic contexts or in speakers' behaviours. Murphy links the phenomenon to the notion of markedness. She points out that while the antonym relation is logically symmetric, there is word-association evidence indicating that specific antonym relations may be mentally stored in a directional way, so that for example the directional link from table to chair is stronger than the link from chair to table. (The small capitals in italics indicate metalinguistic concepts of words.) Murphy regards markedness behaviour in linguistic contexts as predictable from conceptual information, and therefore, she finds it inappropriate for inclusion in the lexicon.

As was mentioned in the section 2 on related research, earlier studies take different standpoints regarding the issue of whether concepts should be integrated into or separated from meaning. In the present study it is, in accordance with cognitive linguistics, assumed that concepts are crucial in the study of meaning. As Langacker (2002:2) puts it: Meaning is conceptualization. According to the view adopted in this study, lexical relations are not stored solely in the lexicon. The relation between words becomes available by virtue of their links to common background frames, as well as to indications of the manner in which their meanings highlight particular elements of these frames (Fillmore 1985:229). The concept is understood to be formed by two units, called profile and base (Langacker 1987). Alternative terms for base are the above-mentioned frame (Fillmore 1982), domain (Langacker 1987, Lakoff 1987) or idealized cognitive model (Lakoff 1987). According to Langacker, the profile "stands out in bas-relief" against the base (here, Langacker cites Susan Lindner). The semantic value of an expression resides in neither the base nor the profile alone, but in their combination (Langacker 1987:183). The willingness to include domains (bases, frames etc.) in the semantics distinguishes cognitive linguistics from some other schools, mainly within structural semantics, where these spheres are rather understood as belonging to something that is not part of the lexical semantics, but as belonging strictly to conceptual information, separate from the meaning of a single word, as was mentioned in section 2 (see e.g. Murphy 2003 Chapter 3 for an overview). In the present paper, the term domain is preferred.

According to Langacker (2002), linguistic meaning is associated with experience-based conceptual archetypes. Examples of such archetypes are Physical object and the Motion of a physical object in space. Further, Langacker (2002:209) writes about energy. The transmission of energy and how energy may cause events together form a domain or an idealized cognitive model, which language users have in common, and which explains and describes patterns in the world. Langacker makes use of the "billiard-ball model" as an archetypal conception of how energy is transmitted from the mover to the impacted object. Langacker argues that this model has influence on our thought process. The model is important both for physical energy and abstract energy, like transmitting information or documents.

Langacker's use of energy as a domain can be contrasted to Johnson (1987), where Force is regarded an image schema. It is slightly unclear whether Johnson addresses force or energy, since he counts notions such as Enablement (for example the ability to carry a child), which, in strictly physical terms, is rather seen as potential or stored energy than force. In the present paper, Physical object and Motion are regarded as conceptual archetypes, while energy is seen as a domain. The image schema Force is not used.

According to Cruse & Togia (1995), antonymy forms a relation between construals. Construal operations should be understood as conceptual processes. The relation involves the structuring of content domains by means of one of a limited repertory of image-schemas. The general notion of opposite would correspond to a single image-schema, which would display diametric opposition, for example manifest in the set-up in a tug-of-war (Cruse 1994:183). The different types (complementaries and antonyms) correspond to more specific image-schemas. Cruse & Togia (1995) suggests that the principal image-schema for antonymy is Scale. For complementarity, the basic image-schema would probably be Existence, and then in terms of presence or absence. (Croft & Cruse 2004:44, 166-167).

The present study further relies on a few other theoretical standpoints suggested within the cognitive linguistic framework. These involve the way meaning is represented in network models and how polysemy is treated.

The network conception, proposed by Langacker, can be regarded as a synthesis of prototype theory and categorisation based on schemas. The members of a category are analysed as nodes in a network, which are linked to each other by relationships (such as extension and specification). One node forms the prototype. The precise configuration of the network is variable, even indeterminate, so every attempt must be seen as an abstraction (2002:267).

Geeraerts (1993) discusses polysemy, and demonstrates how two different operational tests may yield contradictory results concerning the polysemy of a word, and also that one and the same test may show inconsistencies when testing the polysemy of a word. In the article Geeraerts questions the existence of sense boundaries. Instead, he wants to view meaning with the help of a floodlight metaphor, where words are searchlights that highlight, upon each application, a particular subfield of their domain of application. Geeraerts suggests that instead of viewing meanings as "things", meanings should be viewed as processes of sense creation (1993:260). To regard meaning as a process can be connected to construal, which is also a process that involves meaning and context. Cruse (2000), on the other hand, acknowledges sharp sense boundaries, but stresses that these are subject to construal. Cruse distinguishes between a variety of difference and similarity. Polysemy equals full sense boundaries, while there are weaker types of differences, such as facets and ways-of-seeing. The present paper only deals with polysemy, and, following Cruse, departs from a view where sharp sense boundaries exist. However, even if Geeraerts and Cruse have different opinions, both perspectives seem to base their theory on a relatively common ground where the context may modulate some raw-material area of meaning. Therefore, the view of the present paper is that Geeraerts's work need not be rejected or accepted in full, but should rather be taken into consideration as a request to work consciously and carefully with polysemy tests.

There are two main traditions in the study of opposites when it comes to collecting data: on the one hand, studies that examine the relation with the help of the researcher's linguistic intuition (see e.g. Lehrer & Lehrer 1982 and Cruse 1994) and on the other hand, studies that explore the relation using corpus data (see e.g. Justeson & Katz 1991 and Willners 2001). An alternative to these approaches is research which makes use of elicited data (see e.g. Murphy & Andrew 1993 and Paradis & Willners 2006). The present paper tries to combine all three types of data (linguistic intuition, corpus data, and elicited data) as well as introducing a fourth type: dictionary articles. Below, the four types of data are described in more detail:

The first source is formed by 8 Swedish dictionaries, whose articles on levande 'alive' and död 'dead' have been used. The dictionary articles include distinctions on various senses and sub-senses. SAOB is the most thorough of the dictionaries, and its distinction into senses has served as a hypothesis for a plausible model for polysemy in the present study. The dictionaries differ quite extensively from each other when it comes to how many senses are suggested. One dictionary (SAOB) proposes 12 senses for levande 'alive' while another dictionary (NEO) discerns two senses.

The second source is the linguistic intuition of the author, who is a native speaker of Swedish. This source has been essential when performing the polysemy tests. This source has also been important in the process of suggesting "claims", i.e., short sentences which are supposed to capture the sense of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' respectively. An example of such a claim concerning levande 'alive' is: "the referent of the subject/NP has a pounding heart". All the claims are declared in section 6.1.2.

The third source is a corpus, from which all lemmas of levande and död have been gathered. In total, 598 samples of levande 'alive' occurred in the corpus, and 697 samples of the lemma död 'dead'. The corpus (press98, Språkbanken) contains newspaper text, published in major Swedish newspapers in 1998. It contains 12 million tokens, and around 400 000 types. [1] The corpus data have been used to study various types of subjects/noun phrases that are described as levande 'alive' and död 'dead', syntactic distribution of levande 'alive' and död 'dead', as well as their metaphorical and non-metaphorical uses. As was the case with data from linguistic intuition, the corpus data have also been used in the process of suggesting "claims". Finally, the corpus data were used when suggesting the polysemy and the sense boundaries of the words. All corpus uses needed to fit into one of the senses.

The fourth source includes data from 24 adult informants, evenly distributed regarding sex, age, and level of education. The author met each informant individually and showed 6 pairs of pictures. The pictures showed a healthy man - a dead man, a living cat - a dead cat, fresh roses - withered roses, a living tree - a dead tree, a live chicken/hen - a chicken drum stick, and finally an amorous couple - stones. The informant was asked to describe what he/she saw. The interview was video-recorded. The interviews produced data about how language users talk about people, animals and plants that are alive and dead. One main issue was whether the informants would use the word levande 'alive' at all. These data were used for suggesting a model for the relation of oppositeness between levande 'alive' and död 'dead'. After the interview, the same informants were asked to write down the answer to two questions, (1) Hur är något som är levande? 'please describe what something that is alive is like' and (2) Hur är något som är dött? 'please describe what something that is dead is like.' The answers to questions 1-2 were used in the process of suggesting "claims".

The methodology for studying polysemy involves a few tests. The first is the identity constraint test which Lakoff (1970) used. The identity test operates on co-ordinated clauses. One word should be used in a co-ordinated clause, where the word should modify two or more units. The test is positive, if the word can be interpreted in two ways, as long as only one interpretation is valid for both units at the same time. This can be illustrated by the following: The sentence "Mary was wearing a light coat, so was Jane" can either be interpreted as both women wearing bright coats (light in terms of colours), or both women wearing coats made of thin fabric (light in terms of weight). If the test has a positive result for polysemy, a reading will invoke one meaning (either bright for both women, or of little weight for both women), not two (bright for Mary, of little weight for Jane). According to the outcome of the test, light is polysemous. Related to the identity constraint test is the zeugma test: zeugma sometimes occurs when the identity constraint test is performed. The sentence "John and his driving licence expired last Thursday" has a comical effect (a pun or a zeugma) which shows that expire is polysemous. The third test is the truth condition test, used by Quine (1960). A word is polysemous if it can be true and false about the same referent at the same time, such as "Sandeman is a port, but not a port" (=it is a wine, but not a harbour). A fourth test is introduced in Hellberg (2007), which makes use of gradability. If a word can occur both in a gradable and in a non-gradable form with different senses, the word is polysemous.

As mentioned in the section 3 above on theory, Geeraerts (1993) is critical of the polysemy tests, both the identity constraint test (which he refers to as the linguistic test) and the truth condition test (logical test). He further questions whether sharp sense boundaries really exist. The adapted view in this paper is that these tests may serve as a starting-point. In testing the polysemy of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' four tests have been used, but it has not been possible to test every (supposed) sense with the help of all four tests. It has not been possible (or it has felt very awkward) to construct a test sentence where both (supposed) senses occur in a "natural" way. The context-dependence of the tests is one of the points that Geeraerts (1993) refers to in his critique. Further, the tests may indicate a semantic oddness, while, in fact, the oddness may be due to syntactic phenomena (too). The reliability of the method when testing the polysemy of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' in the present paper may thus be subject to discussion, but hopefully, the awareness of such a problem helps to prevent interpretations and arguments that are too far-fetched.

The methodology of the present study has both quantitative and qualitative applications. The quantitative aspects involve frequencies in the corpus, measurable data from the elicitations and rankings in the dictionaries. The qualitative parts concern types of samples in the corpus, odd samples, association patterns in the elicited data and type of definition in the dictionary articles. For the corpus samples, the principle of "total accountability" has been observed. This means that no sample is considered too odd to be included in the analysis (Johansson 1985).

The present study will give an account for the semantics of levande 'alive' and död 'dead'. This task includes examining whether the words are polysemous. The paper will also examine whether the words have somewhat identical distribution. This will be performed by studying word-class and syntactic function (attributive vs. predicative). These two areas have been chosen since at an early, tentative period in the study these areas seemed to include deviations from the general picture in which it was assumed that levande 'alive' and död 'dead' behaved alike. Further, the domains and the metaphorical uses will be studied. One issue that will be addressed is: What is the balance between non-metaphorical senses and metaphorical senses for the two words? Another issue relates to the terms of oppositeness: Are there domains where levande 'alive' and död 'dead' are not opposites? What other opposites can be connected to each word? The paper also wants to examine the gradability of complementaries. Are there patterns for this, i.e., what factors produce or provoke the gradability? Finally the paper will study if levande 'alive' and död 'dead' describe the same kind of things.

In this section, results regarding semantic symmetry, distribution, domains and the relation of oppositeness will be presented and discussed.

First, the polysemy of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' respectively will be investigated. Then, an account of the semantics will be given, and an analysis of whether the words show semantic symmetry. After that, results relating to syntactic distribution will be foregrounded.

When performing the polysemy tests outlined in section 4 on data and methodology, the outcome indicates three senses for levande 'alive' and four senses for död 'dead'. Concerning levande 'alive', Hellberg's gradability test shows that levande 'alive' about humans, animals, plants and micro-organisms (having what is tentatively called here "biological life") is separated from levande 'alive' about artistic expressions (texts, pieces of art, films, theatre performances etc.), ideas, memories, places (meeting-spots, neighbourhoods), and social relations. Levande 'alive' about humans, animals, plants etc. is not gradable (unless humorously or, for humans, if levande 'alive' is used metaphorically, which will be discussed later). An authentic sample about test-tube children from the corpus is shown in (1). In (2), the sentence has been modified by the intensifier oerhört 'tremendously'.

| (1) |

I Sverige föds mellan 1 400 och 1 500 levande provrörsbarn varje år. |

| 'In Sweden, between 1 400 and 1 500 live test-tube children are born every year.' |

| (2) |

? I Sverige föds mellan 1 400 och 1 500 oerhört levande provrörsbarn varje år. (constructed) |

| 'In Sweden, between 1 400 and 1 500 tremendously live test-tube children are born every year.' |

Sentence (2) seems strange, and one gets the feeling that the speaker has some hidden agenda against abortion or that he/she indicates that test-tube children are unusually active in some pathological way. Levande 'alive' about artistic expressions etc. is perfectly gradable, see (3).

| (3) |

En konflikt som gör Alexanders Røslers film ytterst levande. |

| 'A conflict that renders Alexanders Røsler's film extremely alive.' |

In (3), an authentic sample from the corpus is shown. It already contains an intensifier, ytterst 'extremely'. (3) sounds perfectly fine.

When performing the identity constraint test, zeugma occurs. In (4), a constructed sentence is shown, where levande modifies both something that has biological life (crayfish) and something that does not (food traditions).

| (4) |

Innan vi kokar kräftorna är de fortfarande levande, och det tycker jag att vår matkultur här hemma är också. (constructed) |

| 'Before we prepare the crayfish, they are still alive, as is, I think, the food culture in this house.' |

The comical impression that (4) conveys is that the food culture would be alive in a biological way. (This could for example imply that the fridge is full of creeping germs.)

Further tests show that levande 'alive' about humans, animals, plants and micro-organisms has one sense, and levande 'alive' about artistic expressions (texts, pieces of art, films, theatre performances etc.), ideas, memories, places (meeting-spots, neighbourhoods), and social relation has another sense. Levande 'alive' about candles is a third sense. In (5), an attempt is made to let levande 'alive' describe both an artistic expression (a text) and a candle.

| (5) |

? Jag tyckte att Dostojevskijs text kändes lika levande som de stearinljus, i vars belysning jag satt och läste. (constructed) |

| 'I found Dostoevsky's text as living as the candles that lit my reading spot.' |

Sample (5) sounds odd. Either, one gets the feeling that the candles are running about, or that the pages of the book are burning. Intuitively, there is a distance between the text and the candles, and levande 'live' cannot describe both in this way. Hellberg's gradability test supports the suggestion that levande 'live' about candles is another sense, see the authentic sample of (6) where an intensifier has been inserted (within brackets) by the author of this article. The question mark indicates that to insert an intensifier makes the sentence odd.

| (6) |

Hon tar emot i sin valstuga som värms upp av stämningsfulla (? oerhört) levande ljus och talar om hur ideologi och arbete är samma sak för henne. |

| 'She welcomes us into her polling hut, which is heated by atmospheric (extremely) live candles, and speaks about how ideology and work is the same thing for her.' |

Sentence (6) with the intensifier sounds odd. Levande 'live' about candles is not gradable.

In the present article, these three senses of levande 'alive' are labelled levandebio (about humans, animals, plants and micro-organisms), levandeart (about artistic expressions, ideas, memories, places and social relations), and levandecandle (about candles).

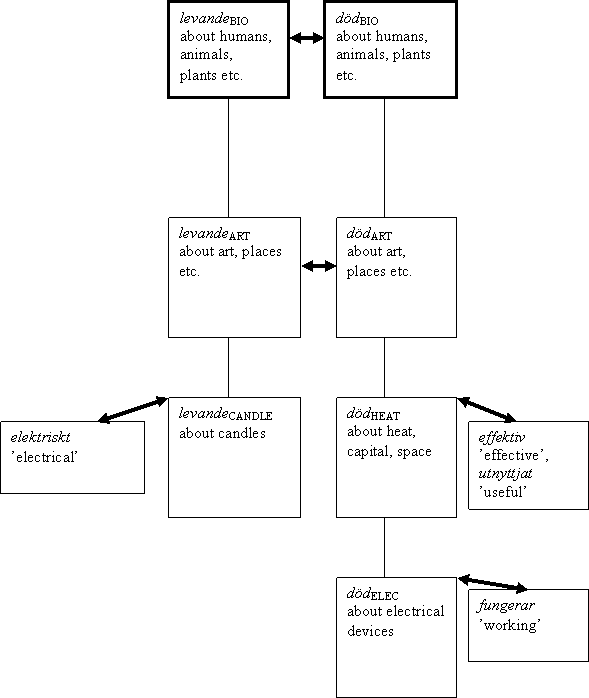

Figure 1. Network model of the semantics of levande 'alive'.

In Figure 1, a network model of the polysemy of levande 'alive' is shown. The bold line around levandebio indicates that this sense is the proposed prototype. This is argued with support from dictionary data, the author's linguistic intuition, and elicited data. Levande 'alive' implying biological life is, without exception, listed first in all dictionaries. Out of 24 informants, 7 wrote definitions referring to a medical/biological domain (such as "has a working heart and brain", "breathes"). Intuitively, the idea that any other sense could be the prototype is odd. However, levandebio is not the most common sense in the corpus. There, levandeart was the most common sense. And among the informants, in actual fact an even greater group, namely 11 out of 24, wrote definitions referring to commitment/influence/connection, clearly pointing out the sense of levandeart. (The numbers of informants overlap, which means that one informant may have included both types of definitions.) Possibly, levandeart is in the process of becoming a new prototype, to take the place of levandebio. Only time can tell if this will be the case.

The dotted arrow between levandebio and levandeart indicates that the relation is extension. The figure partly anticipates results presented in 6.1.2. There, it will be shown that levandebio includes several characteristics, formulated as seven "claims". Of these characteristics, four claims (slightly modified) are valid for levandeart as well. For levandeart, no claims concerning biology are included, but claims on motion, energy, change and expression/influence. If the claims concerning levandebio and levandeart are compared, the claims of levandeart have a wider application and some of the terms used, such as energy, have a metaphorical meaning, while for levandebio, it has a non-metaphorical meaning. This is the reason for the proposal that the relation between levandebio and levandeart is one of "extension". The relation between levandebio and levandecandle is specification. For levandebio, one claim is expressed as "the referent of the subject/NP has the capacity of self-propelled motion". For levandecandle, this claim has been modified into "the referent of the subject/NP includes motion". This should be understood as the referent mimicking the motion of a live referent as the flame of a candle mimics a live being. This restricted sense of levandecandle can thus be regarded as a specification.

Concerning död 'dead', the outcome of the tests shows a correspondence on the one hand between levandebio 'alive' and one of the senses of död 'dead', and on the other hand between levandeart 'alive' and one of the other senses of död 'dead'. It seems that död 'dead' about humans, plants, animals and micro-organisms forms one sense, while död 'dead' about places, artistic expressions, ideas, politics, and social relations forms another sense. Hellberg's gradability test is performed on an authentic sample from the corpus; see (7), where an intensifier has been inserted by the author (within brackets).

| (7) |

I en berättelse om mannen som finner en (? oerhört) död kalv på sina ägor kan han visserligen nå en laddad gåtfullhet. |

| 'In a short story about the man who finds a(n extremely) dead calf on his land, he may certainly reach a loaded mysteriousness.' |

To combine död 'dead' about a calf with the intensifier oerhört 'extremely' sounds odd. To combine död 'dead' about a social relation with the same intensifier sounds good. In (8), an authentic sample is given, and an intensifier has been inserted by the author (within brackets).

| (8) |

Ett mindre skräpkulturellt exempel på västerländska representationer av Orientens erotiskt laddade natur utgörs av Bernardo Bertoluccis Den skyddande himlen från 1990, där ett amerikanskt par ser sitt kalla och (oerhört) döda förhållande plötsligt livas upp när de åker till Nordafrikas öknar. |

| 'A somewhat less trashy culture example of western representations of the erotically charged scenery of the Orient is provided by Bernardo Bertolucci's The Sheltering Sky from 1990, where an American couple see how their cold and (extremely) dead relationship is suddenly enlivened when they go to the deserts of North Africa.' |

To combine död 'dead' about a social relation with an intensifier renders a well-formed expression, and according to Hellberg's test, död 'dead' has at least two senses. The zeugma test supports this suggestion:

| (9) |

? Föräldrarna är döda och det är syskonens inbördes relationer också. (constructed) |

| 'The parents are dead and so are the relations between the siblings.' |

Sentence (9) shows zeugma - there is something odd about it. Relations are not dead in the same way as humans are.

Further, död 'dead' combined with lopp 'heat/race' seems to be another sense. In (10), an authentic sample from the corpus is shown, and within brackets, the intensifier oerhört 'extremely' has been inserted by the author.

| (10) |

Söndagsnattens sifferexercis slutade med (? oerhört) dött lopp mellan blocken, eller 25-25 sedan kommunväljarna visat stor misstro mot Edvinssons politik, hon tappade 8 mandat, från 24 till 16. |

| 'Sunday night's mathematical exercise ended in a(n extremely) dead heat between the blocks, or 25-25 after the voters of the municipality had shown great distrust of Edvinsson's politics, she lost 8 seats, from 24 to 16.' |

This sense of död 'dead' is hardly gradable, as is clear from sample (10), where oerhört 'extremely' makes the sentence odd. [2] That död 'dead' about heats is a separate sense is supported by Quine's test, see (11).

| (11) |

Loppet var dött, men det var inte dött. (constructed) |

| 'The race/heat was dead, but it was not dead.' |

Sentence (11) conveys the impression that the heat did not produce a single winner, but that it nevertheless contained a great amount of excitement. It was dött 'dead' in the sense that there was no winner, but it was not dött 'dead' in the sense that nothing happened. SAOB suggests that död 'dead' about capital (dött kapital 'dead capital') and space/surface (for example in a house) (dött utrymme 'dead surface') has the same sense that död 'dead' about heats has, something which the author's linguistic intuition supports. The heat cannot produce a winner, the capital cannot produce any interest and the space cannot be used. Dött lopp 'dead race/heat', however, is more of a lexicalized phrase than the two other collocations, and as such, it is not gradable. It could be argued that the two other collocations (dött kapital 'dead capital' and dött utrymme 'dead space') may be somewhat gradable. This shows that even within the senses, various uses and contexts may influence and make död 'dead' more or less gradable on a relative scale.

Another candidate for a separate sense is död 'dead' about electrical (etc.) devices, such as computers, TV-sets, engines and telephones. In (12), such a use is shown.

| (12) |

Nakna, utan varken sköldar eller antennula - när högtryckstvättens slang har spruckit och pc:ns skärm är (? oerhört) död - kommer vi då förtvivlat söka en ny verklighet att förankra oss i? |

| 'Naked, with neither shields nor antennula - when the hose of the high pressure washer has split and the computer screen is (extremely) dead - will we then desperately seek a new reality in which to anchor?' |

Sample (12) sounds odd when the intensifier is inserted. Hellberg's test thus suggest that död 'dead' on electrical devices is a sense which is separated from död 'dead' about places, artistic expressions, ideas, politics, and social relations. The zeugma test supports this suggestion, see (13).

| (13) |

? Datorn är död precis som hela den här hålan. (constructed) |

| 'The computer is dead, just like this hole.' |

The sentence sounds odd. The impression is that the computer is död 'dead' in one way (it simply does not work) while the hole (small town) is död 'dead' in another way: calm, quiet, nothing new happens. A third test is performed to see if död 'dead' about electrical devices is a sense, separate from död 'dead' about heats, capital etc.

| (14) |

? Loppet var dött, liksom datorn. (constructed) |

| 'The heat was dead, like the computer.' |

Sample (14) sounds odd, it shows zeugma. One gets the feeling that a heat and a computer are dead in very different ways. A heat is very exciting, full of motion, until it is clear that no one wins, while a computer shows no activity at all.

Död 'dead', according to the outcome of the polysemy test, has four senses, labelled dödbio (about humans, animals, plants and micro-organisms), dödart (about artistic expressions, places, ideas, politics), dödheat (about heats, capital and space), and dödelec (about (mostly) electrical devices such as computers, phones but also engines).

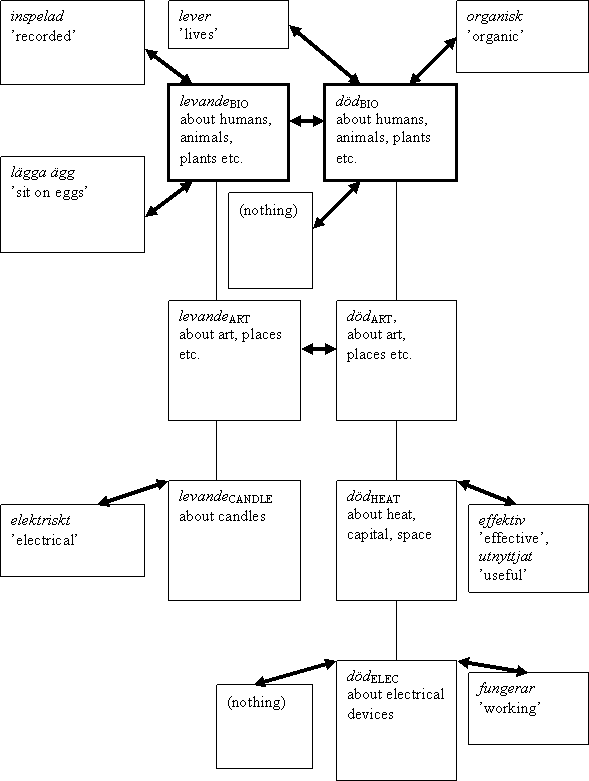

Figure 2. Network model of the semantics of död 'dead'.

In Figure 2, a network model of the polysemy of död 'dead' is shown. It is suggested that dödbio is the prototype. This is argued with support from dictionary data, the author's linguistic intuition, elicited data and corpus data. In the dictionaries, a sense implying lack of biological life is, without exception, listed first. From author's linguistic intuition, this sense comes first to mind. In the elicited data, 5 informants related död 'dead' to something that lacked biological life, while 5 informants related död 'dead' to lack of motion and 5 informants related it to lack of warmth. (5 was the highest number that an area - such as lack of biological life or lack of motion - gained.) In the corpus, this sense was the most common. The relations between the nodes are extension and specification. In order to justify this, results presented in section 6.1.2 are anticipated to some extent. Dödart 'dead' is an extension of dödbio, since the claims for dödart are fewer and have a wider application, and some of the terms, such as energy, have a metaphorical meaning. The relation dödbio - dödheat and the relation dödbio - dödelec is specification. In the case of dödbio - dödheat, the common claim regards propagation/outcome. For dödbio, the subject of the referent/NP cannot propagate any longer, while for dödheat, the referent does not produce any result. This result is rather specific, it concerns the winner of a race, interest of a capital or the use of a space. In the case of dödbio - dödelec, the common claim concerns energy/activity. For dödbio, the referent of the subject/NP does not consume or produce physical energy any longer, while for dödelec, the referent, which is a device often run by electricity, such as a computer or a phone, does not show any activity.

For both levande 'alive' and död 'dead', metaphorical use seems to make the word gradable, however, only in the "art" sense (levandeart and dödart). Section 6.1.2 contains an elaboration of how these senses can be accounted for.

So far, it has been suggested, from the author's linguistic intuition and dictionary data, that levandebio and dödbio have a relation of oppositeness, so that levandebio is the opposite of dödbio and vice versa. The opposite of en levande katt 'a live cat' would be en död katt 'a dead cat'. Likewise, levandeart and dödart seem to be opposites. The opposite of en levande stadsdel 'a live neighbourhood' may be en död stadsdel 'a dead neighbourhood'. But levandecandle seems to have no opposite term in död 'dead' or anything that has to do with (the concept of) death. Instead, it is suggested, still from author's linguistic intuition and dictionary data, that the opposite of levandecandle is elektrisk 'electrical' (levande ljus - elektriskt ljus 'candles - electrical light'). Dödheat has no correspondence in levande 'alive' or (the concept of) life. In order to find opposites to dödheat, a paraphrase needs to be formulated. The opposite of dött lopp 'dead heat' would (still according to the author's intuition) be something like lopp där en vinnare koras 'a heat where a winner can be singled out' and the opposite of dött kapital 'dead capital' would be effektivt kapital 'effective capital', and for dött utrymme 'dead space' possibly utnyttjat utrymme 'space that is being used'. Likewise, dödelec has no correspondence in levande 'alive'. However, it is possible to say something like "Får du liv i datorn?" 'Can you get some life into the computer?', so that the connection död 'dead' = no energy/activity and liv 'life' = energy/activity holds for the referents related to this use (computers, phones, cars etc.) The opposite of död about computers, phones, TV-sets, engines etc. would, anyway, not be levande 'alive', but (according to the author's intuition) a paraphrase like som fungerar 'working' - or, rather, just a computer, a phone, a TV-set, an engine - since these devices are normally expected to work.

Figure 3. Relations of oppositeness between levande 'alive' and död 'dead' and other words.

In Figure 3, it can be seen that levande 'alive' and död 'dead' are opposites in some senses, but not in others. Two senses of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' have a possibility of being symmetrical, while this is not the case for the last sense of levande 'alive' (levandecandle) and for the two remaining senses of död 'dead' (dödheat and dödelec). In the next section, the semantics of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' will be examined, and there will be an investigation of whether the two senses of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' show semantic symmetry.

In order to try to account for the semantics of each sense of levande 'alive', and each sense of död 'dead', claims are formulated. The claims have been formulated by analysing elicited data, the author's linguistic intuition, dictionary articles and corpus data.

Claims concerning levandebio 'alive'

- the referent of the subject/NP has a pounding heart

- the referent of the subject/NP has a working brain

- the referent of the subject/NP is a system, which consumes and produces energy

- the referent of the subject/NP is a system that can propagate

- the referent of the subject/NP undergoes some kind of change

- the referent of the subject/NP has the capacity of self-propelled motion

- the referent of the subject/NP expresses itself

For the claims concerning levandebio, data from the elicitations have mainly been used. As mentioned in relation to the network model of levande 'alive' (see Figure 1), 9 informants (out of 24) related to movement. 7 informants described levande 'alive' in terms of biological functions, such as "working heart and brain". 4 informants mentioned change. Definitions related to energy, such as kraftfull 'powerful', were suggested by 3 informants and 3 informants wrote something about light and/or sound (this can be connected to energy and to the capacity of expressing oneself). The author's linguistic intuition also formed a useful source in this process. Common knowledge about biology, such as what distinguishes live plants or germs from dead ones is included in this intuition. The corpus was used to discern sub-senses (see metonymic uses and the "levande uppslagsbok-type" 'walking encyclopaedia-type' below).

Levandebio is the prototype, and, in terms of number of claims, the richest. For some uses, all the claims are relevant, for some uses, only a few (or one). For a young, healthy man/woman, probably all claims are valid, while for a germ, only the claims about energy and propagation hold. The claim about change should be understood in terms of growing, ageing or some other physical change of the body. The claim about expressing oneself should be understood as humans and animals being able to communicate in some way: talking, expressing feelings through mimicry or body language, but also (for humans) to express oneself in more elaborate ways, such as painting, performing music etc. Some of the claims, such as the claim about motion, are more central, and others are more peripheral.

It could perhaps be argued that the claims should ideally operate on the same level of abstraction. The claim involving a system which consumes and produces energy can subsume some of the other claims. Still, it is valuable to retain the claim on energy. The first reason is that it captures well the conditions for live micro-organisms and plants (they do not have properties like pounding heart, brain, capacity to express themselves, etc.), and the second reason is that energy (however abstract) seems to be a key concept that is hard to ignore for both levande 'alive' and död 'dead', as will be shown below.

The main opposite to levandebio seems to be död 'dead', but in certain sub-senses, it may have other opposites. Levandebio may be contrasted to 'fake'. This is the case in levande blommor 'fresh flowers' - konstgjorda blommor 'artificial flowers', which is the opposition that the dictionary SAOB suggests. "Fake" may also include various mimetic reproductions, such as pictures, animations, visual recordings, audio recordings as well as toys depicting real animals. The claims "has a pounding heart" and "capacity of self-propelled motion" seem most important for this sub-sense of levandebio 'alive'. A real person has a pounding heart and can move, while a picture has no heart and cannot move. Levande 'alive' is sometimes used in the expressions livs levande 'in real life' and i levande livet 'in real life', which refers to meeting somebody (a person) or something (an animal), as opposed to seeing them in pictures, on TV etc., see (15).

| (15) |

Hur många svenskar har sett livs levande lodjur i skogen? |

| 'How many Swedes have seen lynxes in real life in the forest?' |

To meet somebody, face to face, in a canonical encounter (Clark 1973) seems to be an essential quality connected to levande 'alive'.

Metonymic uses

There are also metonymic uses (sub-senses) of levandebio, where levande describes not a human, but a group of humans, see (16), or an activity performed by humans, see (17).

| (16) |

Världens äldsta nu levande rockband, ungefär, i en Las Vegas-show à la grotesque. |

| 'The world's oldest rock band still alive, or something like that, in a Las Vegas show à la grotesque.' |

| (17) |

Varje stad och liten ort har fest på gatorna med levande musik, gatustånd, eldar och parader. |

| 'Every town and little community organises a party in the streets, with live music, market stalls, bonfires and parades.' |

In (16), a rock band is called levande 'alive', and in (17), music is described as levande 'alive' ('live' is a more idiomatic translation). The latter use (sub-sense) is rather common in order to separate live performances from recorded ones, be it music, theatre or other forms of culture. The opposite is then not död 'dead' but rather inspelad 'recorded'. To use levande in this sub-sense is an extension of levande as opposed to fake etc., that was discussed in the preceding paragraph.

The levande uppslagsbok 'walking encyclopaedia'-type

An interesting use of levande 'alive' is when the participle describes a human referred to by a noun which is normally used about inanimate objects.

| (18) |

Hon berättar att det görs regelbundna mätningar om vilka som lyssnar och beskriver dem som en blandning av män och kvinnor, levande uppslagsböcker eller mer allmänt musikintresserade personer. |

| 'She tells that regular measurements are taken concerning who listen, and she describes them as a mixture of men and women, walking encyclopaedias or people with a more general music interest.' |

The noun uppslagsbok 'encyclopaedia' normally refers to an inanimate object. Here, levande 'alive' has its non-metaphorical sense (levandebio) - it refers to a human that has a pounding heart, working brain, etc., but the noun uppslagsböcker 'encyclopaedia' is used in an extended sense. The idea can also be referred to as vandrande uppslagsverk 'walking encyclopaedia' / uppslagsverk på två ben 'encyclopaedia on two legs', which shows how important the claim about motion is. Other uses are levande exempel 'live example' and levande illustration 'live illustration'. The opposite of levande 'alive' in this case is not död 'dead', but rather inanimate. Possibly, a use of död 'dead' meaning 'has never had life'.

Generic sense

Another interesting case is when levande 'alive' is used in the expression föda levande ungar 'be viviparous'. Here, levande 'alive' is used in a generic sense. It is possible for one specific animal to be viviparous and give birth to dead offspring at the same time. The opposite to levande 'alive' is then not död 'dead', but rather a paraphrase where for instance lägga ägg 'lay eggs' is included (for some reason, mammals are often contrasted with birds and other species that give birth to their offspring in this way).

Claims concerning levandeart

- the referent of the subject/NP undergoes some kind of change

- the referent of the subject/NP moves, or includes motion

- the referent of the subject/NP expresses something that makes an impact

- the referent of the subject/NP has, in relation to a norm, a high level of energy

For the claims concerning levandeart, elicited data, the author's linguistic intuition and corpus data have been used. For levandeart, the number of claims has been reduced compared to levandebio. Change, motion, expression and energy form the claims, and each claim has a counterpart in levandebio.

The claim about change should be understood as the referent changing, either in a physical way (like a town growing bigger) or in a more abstract way (like a film that develops an intrigue in an unexpected way). In sample (19), the question is raised of whether a human who feels constant happiness (that does not undergo any change) is levande 'alive'.

| (19) |

Men är en människa i ett tillstånd av oföränderlig lycka ens levande? Den konstanta lyckan utesluter alla kontraster, alla känslor som inte innebär lycka, allt motstånd som alstrar aggression eller vånda, det vill säga de kontraster i erfarenhet och känsla som utgör livets väv. |

| 'But is a human being, in a state of unchanging happiness, even alive? The constant happiness excludes all contrasts, all feelings that do not mean happiness, all resistance that generates aggression or torment, that is the contrasts of experience and feeling that form the web of life.' |

The rest of the claims about levandeart have been slightly modified from levandebio 'alive'. The claim concerning motion is, for levandebio, formulated as the referent having the capacity of self-propelled motion. The claim about levandeart reads "moves or includes motion". This distinction (that the referent does not move itself, but rather includes motion) is relevant for levande 'alive' about places, where the place does not move, but people, vehicles etc. within the area do, see (20).

| (20) |

Vi vill skapa ett levande centrum och få hem köpkraften igen, säger Jan Lejdelin. |

| 'We want to create a living city-centre and bring back the purchasing power again, says Jan Lejdelin.' |

The next claim concerns expression. For levandebio, the referents may express no matter what, but for levandeart, the referent should express something that makes an impact (touches, moves) an addressee. This is exemplified by the sample (21).

| (21) |

Jag, en bleksiktig protestant, har mött levande ikoner med en oerhörd utstrålning. |

| 'I, a bloodless Protestant, have met live icons with a tremendous charisma.' |

In this sub-sense, the canonical encounter (although now the encounter is not between two live human beings, but between a human being and an object) is present again. A referent, that can convey a feeling of such an encounter, may be described as levande 'alive'. Sample (22) is an even clearer example of this.

| (22) |

"Konsten är helt död om ingen tittar på den. Men så fort någon tittar ett endaste ögonblick så blir den levande" skriver hon i förordet. |

| '"Art is totally dead if nobody is watching it. But as soon as somebody is watching for only a single moment, it becomes alive" she writes in the preface.' |

The last claim is about energy. For levandebio, the claim reads that the referent is a system that consumes and produces energy. For levandeart, it is rather the production of energy that is relevant, and now energy in a more abstract form than for levandebio. What is described as levandeart 'alive' has a high level of energy, it is strong, powerful and active. A sample where this levande 'alive' is used is shown in (23).

| (23) |

Den faktorn ska man inte förakta i ett land där fotbollsspelaren Denis Law kunde utnämna den engelska VM-segern 1966 till sitt livs sorgligaste dag och där segern vid Bannockburn 1314 fortfarande är ett levande minne. |

| 'This fact should not be despised in a country where the football player Denis Law could describe the English World Cup victory in 1966 as the saddest day of his life, and where the victory at Bannockburn 1314 still is a living memory...' |

It is interesting to note that for levandeart, which concerns levande in an extended (metaphorical) sense, the characteristics that constitute the claims also get a more extended meaning: this holds partly for the claim concerning change (the change can be either physical or abstract), and for the claim concerning energy (the energy is not measurable in Joule anymore, but has a more abstract meaning).

In this sense, levande 'alive' is gradable (see (3) about a film that is ytterst levande 'extremely alive'). So, this is a "certain context" as discussed by Jones (2002), Murphy (2003) and Paradis & Willners (2006). Probably, the aspects of "expresses something that makes an impact" and "has a high level of energy" are the characteristics of the referent that can be gradable (a referent can affect more or less, and it can have more or less energy).

Claims concerning levandecandle

- the referent of the subject/NP includes motion

The third sense of levande, which is used in the collocation levande ljus 'candles', has only one claim, concerning motion. It has been formulated by analysing dictionary data and the author's linguistic intuition. It is the flickering flame of the candle that mimics the irregular motion of live beings. Levandecandle has a metaphorical sense. The motion of the flame gives the impression of being "self-propelled", even if language users know it is not.

Claims concerning dödbio

- the referent of the subject/NP has not a pounding heart (any longer)

- the referent of the subject/NP has not a working brain (any longer)

- the referent of the subject/NP does not consume or produce energy (any longer)

- the referent of the subject/NP cannot propagate (any longer)

- the referent of the subject/NP does not change (any longer)

- the referent of the subject/NP has no capacity of self-propelled motion (any longer)

- the referent of the subject/NP does not express itself (any longer)

The claims concerning dödbio have been formulated mainly by analysing elicited data and the author's linguistic intuition. As was mentioned in relation to the network model of död 'dead' (see Figure 2), informants mentioned lack of biological functions (5 informants), lack of motion (5 informants) and lack of warmth (5 informants).

It seems as if the claims for dödbio mirror the claims for levandebio in a symmetrical way, so that on the whole the negated claims concerning levandebio are valid for dödbio. The special uses of levandebio, however, have no correspondence in dödbio. The metonymic sub-sense, exemplified by levande musik 'alive (live) music', the generic type in föda levande ungar 'be viviparous lit: give birth to live offspring' and the interesting collocation where the participle is non-metaphorical and the noun is metaphorical (levande uppslagsbok 'walking encyclopaedia') do not take död 'dead' as their opposite. Further, there is a use of dödbio, where död 'dead' describes referents that have never had biological life, see (24).

| (24) |

Jag kunde slå på folk och döda ting som bilar för skojs skull. |

| 'I could beat people and dead things like cars just for fun.' |

For this use, the relevant claims would be that the referent does not have a pounding heart, a working brain, etc. The time adverbial "any longer" is absent. The opposition of döda ting 'dead things' can either be levande varelser 'alive (living) creatures', if the creature has life in the present time, or the opposition is something like organiskt material 'organic substance', which is about a substance that has had life, but does not any more, such as dead plants, dead bodies etc. Here is another difference between levande 'alive' and död 'dead', since levande 'alive' seldom describes such substances (that have had life, but do not anymore).

To sum up, levandebio and dödbio are relatively symmetrical when it comes to their semantics. However, there are some uses (metonymical etc.) where the use differs.

Claims concerning dödart

- the referent of the subject/NP involves little change

- the referent of the subject/NP involves little motion

- the referent of the subject/NP involves little expression

- the referent of the subject/NP has, in relation to a norm, a low level of energy

The claims have been formulated by analysing all four types of data.

For dödbio the claims express the referent's lack of biological functions. For dödart, other functions are relevant; still, they have their counterparts in the biological ones. The relation between dödbio and dödart mirrors the relations between levandebio 'alive' and levandeart. It is interesting to note that for dödart, the functions may exist, but not to an adequate extent (or quality). In sample (25), two restaurants are described by using dött 'dead'.

| (25) |

För partyfolket: Skipper's och Skagerack. Nää! Helt dött! Så ska det inte behöva se ut en torsdagskväll. |

| 'For those who like to party: Skipper's and Skagerack. Nope! Totally dead! It need not look like this on a Thursday night.' |

It is reasonable to believe that the restaurants in sample (25) do not lack motion totally. There are probably some waiters moving around and perhaps a few guests, too, but not to the extent that can satisfy the taste of the speaker.

In this sense, död 'dead' is gradable (see (8) about an extremely dead relationship). So, this is a "certain context" as discussed by Jones (2002), Murphy (2003) and Paradis & Willners (2006). It seems as if the two claims about expression and energy are in focus when dödart is used gradably. A very low level of energy would trigger a use such as väldigt död 'very dead' and so would a referent that involves very little expression. Change and motion do not seem as sensitive to gradability or perhaps it is not so meaningful to describe them as "more of" or "less of".

It seems that levandeart and dödart are relatively symmetrical when it comes to their semantics.

A claim concerning dödheat

- the referent of the subject/NP does not produce any result

The claim has been formulated by analysing dictionary data, corpus data and the author's linguistic intuition.

The claim reads that the referent does not produce any result: there is no outcome. The claim can be related to the claim concerning dödbio, that the referent cannot propagate any longer. Capital that does not yield interest is called dött capital 'dead capital', and time which is not used in an efficient way is called dödtid 'dead time' (this is a compound, but semantically related). A heat that does not produce a winner is called dött lopp 'dead heat'. Propagation means to produce an offspring, and the link with the production of something valuable is rather clear.

There is no correspondence to levande 'alive' for this sense.

A claim concerning dödelec

- the referent of the subject/NP involves no energy/shows no activity (does not work)

The claim has been formulated by analysing corpus data and the author's linguistic intuition.

The referent is often an electric device such as a telephone, a computer, a TV-set, a car engine (the latter runs on petrol but depends on battery power for ignition). For dödbio, biological functions are in focus, while dödelec concerns non-biological, electrical, and for the device fundamental functions. The referent does not work as expected - it does not work at all. It does not involve any energy/shows no activity. Here there is a clear connection to dödbio, whose claims includes one about not consuming and producing energy.

There is no counterpart in levande 'alive' for this sense.

In this section, word class and attributive versus predicative function will be investigated.

Word class

According to the Swedish standard grammar (Teleman et al. 1999), the words levande 'alive' and död 'dead' belong to different word classes. Levande 'alive' is a participle, while död 'dead' is an adjective. Some dictionaries, however, treat both words as adjectives. A comparison between words related to 'life' and 'death' can be undertaken. For 'life', there are the verb leva 'live', the noun liv 'life' and the participle levande 'alive'. There is no morphologically simple adjective in the "life-family". The adjective livlig 'lively' is a derivation, while livfull 'vital' is a compound. It can be noted that these adjectives do not concern biological functions in the first place, but rather qualities such as (abstract) energy. There is also the seldomly used participle levd 'lived', which is present in the form upplevd 'experienced'. For 'death', there are the verb dö 'die', the noun död 'death', the adjective död 'dead' and the participle döende 'dying'. There is also another verb in this "family", namely döda 'kill', to which the participles dödande 'killing' and dödad 'killed' are related. This causative meaning, 'make somebody die' is not lexicalised in the "life-family", which means that the meaning 'make somebody live' does not correspond to a single word related to leva 'live'. This may instead be expressed by föda 'give birth to'. The compound participle livsuppehållande 'life-sustaining' may be related, too. On the whole, the concept 'dead' seems richer; it has more lexicalisations, and these lexicalisations are formed by morphologically simple words. This fact can be attributed to the heavy information value that the concept 'dead' has, compared to 'alive'. Of the two terms, levande 'alive' is unmarked and död 'dead' is marked. Levande 'alive' is evaluatively positive, while död 'dead' is negative (one of the criteria in Lehrer 1985 that indicate what term is unmarked and what is marked).

Further, död 'dead' often takes the verb lever 'lives' as its opposite. If a question is posed whether a person is dead or alive in Swedish, this is either phrased as Lever din mamma? 'Does your mother live?' or Är din mamma död? 'Is your mother dead?', never as ?Är din mamma levande? 'Is your mother alive?' The negating answer to a question like Är din mamma död? 'Is your mother dead?' would be Nej, hon lever 'No, she is alive/she lives', never ?Nej, hon är levande 'No, she is alive'. Here, lever 'lives' and är död 'is dead' form an opposite pair.

The fact that död 'dead' often takes lever 'is alive' as its opposite may partly be attributed to the fact that leva 'live' and levande 'alive' seemingly have very similar meaning. The opposites concerning leva 'live', levande 'alive' and död 'dead' may be grouped as in Table 1.

Table 1. Opposites related to the concepts 'alive' and 'dead'.

| Words of the "life-family" |

Words of the "death-family" |

leva 'live'

Sample: Idag lever betydligt fler med aids...

'Today, considerably more people live with aids...' |

dö 'die'

Sample: Människorna dör inte längre i aids...

'The people do not die from aids anymore...' |

leva 'live'

Sample: Nu i fredags såg Henry Holmberg, far till Paulina Brolin, videon: - Det var uppmuntrande att se att de lever.

'Last Friday, Henry Holmberg, the father of Paulina Brolin, watched the video: - It was encouraging to see that they are alive (lit. that they live).' |

vara död 'be dead'

Sample: Haideh är död sedan några år.

'Haideh has been dead for a few years.' |

vara levande 'be alive'

Sample: Även om ett foster är levande...

'Even if a foetus is alive...' |

vara död 'be dead'

Sample: Lena Palm är en av dem som själv fött ett barn som var dött.

'Lena Palm is one of those who, herself, has given birth to a child who was dead.' |

The verb leva 'live' takes both dö 'die' and vara död 'be dead' as its opposites. (The linguistic intuition of the author is the source for this claim.) The verb form leva 'live' probably stresses the concept as a state, while the participle levande 'alive' instead stresses the concept as a quality. The participle levande 'alive' can be used as a predicative, as in the sample Även om ett foster är levande 'even if a foetus is alive' from Table 1, a fact which implies that the participle has some similarities to an adjective. Adjectives in general have greater possibilities to express qualities than verbs have. In order to contrast with vara död 'be dead', leva 'live' seems more frequent in Swedish than vara levande 'be alive'. Aktionsart is also an issue here. Both leva 'live' and vara död 'be dead' describe states, while dö 'die' describes a punctual event, which can be contrasted both with leva 'live', but also with födas 'be born', which describes a punctual event. Cruse (1986) calls be born - live - die a lexical triplet. While live refers to a continuance of a state, be born and die refer to a change to an alternative state (Cruse's terms). This difference (maybe asymmetry), regarding what Aktionsart the verbs have, probably has an impact on how the related word levande 'alive' is used, and offers a hint on why it is not used as the opposite of död 'dead' in phrases such as Är X död? 'Is X dead': the focus in such a question is the state of X, not his/her qualities.

This can be taken even further. When informants were asked to describe two pictures, one which showed a live person, another one which showed a dead person, very few mentioned levande 'alive' in relation to the live person, while they did mention död 'dead' or sårad 'hurt' for the dead person. When describing the live person, remarks such as glad 'happy' or som dansar 'dancing' dominated. In this context, en död man 'a dead man' has just en man 'a man' as its opposite.

Attributive versus predicative

All the corpus samples, including both metaphorical and non-metaphorical uses of levande 'alive' and död 'dead', have been sorted and categorised according to their syntactic properties. The adjective död 'dead' / the participle levande 'alive' is either attributive, as död kropp 'dead body', predicative, as Betty är död 'Betty is dead', or the head of a noun phrase, as de döda 'the dead ones'. Such a noun phrase may function as subject in a clause. The words can also be part of a sentence, which does not form a clause: Fem döda i Paris-Dakar-rallyt 'Five dead in the Paris-Dakar Rally'. This type is rather common in headlines in the corpus, which consists of newspaper articles. Finally, the word can stand alone in an adjective/participle phrase, as Helt dött! 'Totally dead'.

The balance between the various syntactical constituents for levande 'alive' and död 'dead' respectively is found in Table 2.

Table 2. The balance of syntactical constituents for levande 'alive' and död 'dead'.

| |

levande 'alive' N=598 |

död 'dead' N=697 |

Attributive |

75% |

37% |

Predicative |

20% |

39% |

Head of a noun phrase |

5% |

18% |

Part of sentence, which does not form a clause |

- |

4% |

Adjective/Participle phrase |

0% |

1% |

Total |

100% |

99% |

As can be seen in Table 2, levande 'alive' and död 'dead' have very different patterns when it comes to their syntactic function in the clause. Levande 'alive' occurs mainly in the attributive position (75%), while död 'dead' appears as often in the attributive position (37%) as in the predicative position (39%). For levande 'alive', the predicative position is not so common (20%), while other positions are very rare. For död 'dead', the adjective is head of a noun phrase in one fifth of the samples (18%). In order to explain this asymmetry, a few words should be said about the predicative and the attributive position. The predicative is part of the proposition of a clause, while the attributive does not need to be. This would mean that the word död 'dead' is more often part of the proposition in the corpus, than the word levande 'alive' is. In newspaper text, it can be assumed that the fact that somebody is dead has a higher information value than the fact that somebody is alive. This can be related to död 'dead' being marked, while levande 'alive' is unmarked. The more expected a certain quality regarding an object is, the less necessary it is to express this quality with an adjective (Ungerer & Schmid 1996). If we talk about a human or an animal, we do not state that it is alive, since this is presupposed. Probably it is part of the semantics or the prototype of a human, a cat, a dog, etc. that it is alive. In (26), a sample where död 'dead' is in the predicative position, and part of the proposition, is shown.

| (26) |

En pojke som enligt polisen med stor sannolikhet är den försvunne tioåringen från Rinkeby, påträffades på måndagseftermiddagen död vid Eggeby Gård på Järvafältet, inte långt från Rinkeby. |

| 'A boy, who, according to the police, is very possibly the missing ten-year-old from Rinkeby, was found dead on Monday afternoon at Eggeby Gård at Järvafältet, not far from Rinkeby.' |

There are cases where levande 'alive' occurs in the predicative position, and is part of the proposition, with a high information value. This is the case if a person expected to have been killed in an accident is, nevertheless, found alive, see (27).

| (27) |

Schaktet ligger 60 meter under markytan och strax ovanför det utrymme där den 24-årige gruvarbetaren Georg Hainzl återfanns levande efter att ha suttit instängd i 10 dagar. |

| 'The shaft is located 60 metres below the surface and right above the space where the 24-year-old miner Georg Hainzl was found alive after having been entombed for 10 days.' |

Uses like (26) are rather common in the corpus, while uses like (27) are rare. According to Bolinger (1967) and Teleman et al. (1999), adjectives in an attributive position often refer to the function of the referent, while adjectives in predicative position concern qualities of the referent, regardless of function. Levande 'alive', which is more common as attributive, would then describe the referent relating to its qualities as, for instance, författare 'author' or konstnär 'artist' (examples from the corpus), while död 'dead' would to a greater extent describe the full referent, the human being behind the nominal phrase en kvinnlig pilot 'a female pilot' or morfar 'grandfather' (examples from the corpus). According to the intuition of the author, this is in accordance with how levande 'alive' and död 'dead' are used. If a female pilot is dead, her whole being is gone. But if an artist is described as levande 'alive' (in a metaphorical sense), this property mainly concerns her oeuvre/her artistic qualities.

The corpus samples have been categorised and sorted according to whether the sense of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' can be described as metaphorical or non-metaphorical. Non-metaphorical sense is identical to levandebio and dödbio, while metaphorical sense subsumes the other senses. In Table 3, the numbers are shown.

Table 3. Balance of non-metaphorical and metaphorical sense in the corpus.

| |

levande 'alive' N=598 |

död 'dead' N=697 |

Non-metaphorical sense |

37% |

79% |

Metaphorical sense |

62% |

21% |

Non-categorised |

1% |

0% |

Total |

100% |

100% |

From Table 3 it is clear that usages of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' differ widely in terms of metaphorical uses. Metaphorical use is by far the most frequent in the corpus for levande 'alive'. Nearly 2/3 of the uses of levande 'alive' involve the metaphorical sense. For död 'dead', the opposite is true: non-metaphorical use is definitely the most common in the corpus. 4/5 of the uses of död 'dead' involve the non-metaphorical sense. The explanation of this phenomenon is probably that levande 'alive' is redundant information in most cases where the non-metaphorical sense could be used. The high frequency of non-metaphorical död 'dead' is supposedly due to the fact that död 'dead' is marked and has a high information value.

The samples where levande 'alive' occurs in its non-metaphorical sense relate to referents that are human beings, animals, plants and micro-organisms. The balance between these referents can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4. The balance of referents that are described by non-metaphorical levande 'alive'.

| Type of referent described as levande 'alive' |

Frequency N=221 |

Human beings |

58% |

Animals |

24% |

Plants |

3% |

Micro-organisms |

4% |

Unspecified |

11% |

Total |

100% |

Samples about animals involve contexts about transportation across nation borders in relation to legislation, as in the sample shown in (28).

| (28) |

Bakgrunden till de stränga regler för hantering av levande importerade kräftor är alltså att signalkräftor och andra amerikanska kräftarter alltid utgör ett hot mot flodkräftan eftersom den har pestsvampen med sig i skalet och överför sjukdomen till flodkräftan. |

| 'The strict rules regarding the handling of live imported crayfish should be understood against a background where the American species always pose a threat to Swedish crayfish since it bears the plague in its shell and transmits the disease to the Swedish crayfish.' |

Animals may serve as food, and as such, the animals leave one category (live beings) for another category (food). Food is prototypically not alive. Although there is an obvious connection between meat (food) and a live being, this connection seems to be denied to some extent in the human mind. In the elicitation test, two pictures, one of a live hen and one of a chicken drum-stick were organized as a pair. The sight of the two pictures mostly aroused laughter among the informants. The laughter may be interpreted as a way of hiding feelings of guilt. Several informants elaborated on this and made comments like "When you see it like this... you lose your appetite..."

Still other uses of non-metaphorical levande refer to living creatures in general ("unspecified" in Table 4), including expressions such as allt levande 'all that is alive', levande varelser 'living creatures', and levande material 'living matter'.

It is interesting to see that levande 'alive' modifies animals nearly half as often as it modifies humans in the corpus, although newspaper text has so much more text on humans compared to animals. Both for humans and animals, being alive is part of the prototype. The reason that animals are nevertheless described as levande 'alive' is probably that live animals form a topic in texts on customs and legislation (8 of the samples are from the same article on legislation on importing crayfish, see sample (28) above). The animals are described more as goods, for which being alive is not part of the prototype.

The samples where non-metaphorical levande 'alive' nevertheless is used about humans, relate, for instance, to people discovered alive after accidents, as was the case in (27) in the preceding section, or people who have been buried alive or burnt alive, see (29).

| (29) |

Enligt samtida källor brändes de levande på berget, med ansiktena vända mot Solberga prästgård. |

| 'According to contemporary sources, they were burned alive on the mountain, with their faces turned towards Solberga vicarage.' |

In the context, to be burnt alive is non-expected, hence the need to spell it out. Other uses involve collocations such as levande uppslagsbok 'walking encyclopaedia' which was discussed above. Still other uses where non-metaphorical levande 'alive' describes humans involve people sharing a canonical encounter, as opposed to recordings/reproductions. A rather substantial proportion of the samples involve metonymical expressions such as levande musik 'live music', which are related to levande människor 'live people'. The balance of the various uses is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. The balance of uses where levande 'alive' describes humans.

| Type of use where levande 'alive' describes humans |

Frequency N=128 |

Metonymical expression related to humans |

13% |

Expressions of the levande uppslagsbok 'walking encyclopaedia'-type |

23% |

Other uses |

63% |

Total |

99% |

It is interesting to note that the metonymical expressions of the type levande musik 'live music' together with the expressions of the type levande uppslagsbok 'walking encyclopaedia' form a rather large part (36%) of the uses in which levande 'alive' describes humans. In these uses, levande 'alive' does not modify a noun for which the prototype includes that 'it is alive' (musik 'music', uppslagsbok 'encyclopaedia' etc.)

The relative frequency of the types of referents described as död 'dead', is shown in Table 6.

Table 6. The balance of referents that are described by non-metaphorical död 'dead'.

| Type of referent described as död 'dead' |

Frequency N=548 |

Human beings |

92% |

Animals |

7% |

Plants |

- |

Micro-organisms |

1% |

Unspecified |

0% |

Total |

100% |

As can be seen in Table 6, non-metaphorical död 'dead' modifies nouns referring to humans in the great majority of samples. Animal referents are few, and referents formed by plants and micro-organisms are even fewer. Referents that are unspecified are rare, too. The type of referents probably mirrors the balance of general newspaper text about human beings vis-à-vis text about animals more accurately than was the case for levande 'alive', see Table 4. A comparison between Table 4 and Table 6 reveals a difference between the referents non-metaphorical levande 'alive' and non-metaphorical död 'dead' are used to describe. Non-metaphorical levande 'alive' describes humans less than non-metaphorical död 'dead', and when it does, two special constructions are included: one consists of metonymical expressions such as levande musik 'live music' and one is a use in which the noun has a metaphorical sense, as levande uppslagsbok 'walking encyclopaedia'. Further, levande 'alive' describes more animals, plants, micro-organisms and unspecified referents (such as allt levande 'all alive') compared to död 'dead'. The reason for the differences is probably the fact referred to above that levande 'alive' offers redundant information for human beings.

The metaphorical uses of levande 'alive' and död 'dead' have slightly different domains. For metaphorical levande 'alive', the domain of artistic expression, culture and tradition is the greatest. For metaphorical död 'dead', place is the greatest domain (followed by artistic expression). As has been mentioned above, electrical devices are described as död 'dead', but not as levande 'alive', and the same goes for heats (races); these are described as död 'dead', but not as levande 'alive'. Humans can be described by metaphorical levande, as in (30), but to use död 'dead' in this way is rare.

| (30) |

För människan är bara levande om hon erkänner sin delaktighet i andras liv, det vill säga i historien, i skulden, i en gudom som bara gör sig påmind genom sin frånvaro. |

| 'Because human beings are only alive if they admit their part in other people's lives, that is, in history, in guilt, in a divinity that only makes itself reminded through its absence.' |

In (30), a human is described as levande 'alive' if (and only if) he or she admits that she has influence on other people's life.

In the light of the results presented so far, it is possible to refine the map of the relation of oppositeness between levande 'alive' and död 'dead', which was first shown in Figure 3. Now, more opposites can be added to the three senses of levande 'alive', as well as to the four senses of död 'dead'.

Figure 4. Updated map showing relations of oppositeness between levande 'alive' and död 'dead' and other words.