Background: Regional English Speech Project and the Cambridgeshire Dialect Grammar

I. Regional English speech project at the University of Helsinki

The regional English speech project was launched in the early 1970s at the University of Helsinki. Professor Tauno F. Mustanoja, who held the chair of English Philology in the years 1961-1975, was the initiator of the project in collaboration with Professor Harold Orton, University of Leeds. Mustanoja gathered a group of Finnish students who all had a research interest in dialect syntax. The members of this group set off to do fieldwork in England. After Prof. Mustanoja’s withdrawal from the project at the beginning of the following decade, Professor Ossi Ihalainen succeeded him as project coordinator (http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/CoRD/corpora/Dialects/history.html). Ihalainen’s expertise in using computers to aid language study gave birth to the idea of creating a computerised collection of English texts. The Helsinki Corpus of English Texts: Diachronic and Dialectal project, co-directed by Professsors Matti Rissanen and Ossi Ihalainen, was launched in the early 1980s. It was originally intended that this corpus would contain a diachronic section, covering the period of circa 750 to1700, and a dialectal section, based on transcriptions of interviews with speakers of English rural dialects conducted by the Helsinki Dialect Syntax Group (as the group of Finnish students was called) in the 1970s (see, e.g., Ihalainen 1988a, 1988b, 1990a; Ihalainen et al. 1987). The diachronic corpus, now usually referred to as the Helsinki Corpus (HC), was completed and released in 1991, but the compilation of the dialect corpus was postponed due to Ihalainen’s untimely death in 1993. In 1997, Docent Kirsti Peitsara took charge of the project. Under the coordination of Peitsara, the hand-written transcriptions were transferred to text files and the digitisation of the first reel-to-reel tapes began. With the dialect corpus taken under the wing of the Research Unit for Variation and Change in English (later the Research Unit for Variation, Contacts and Change in English) (VARIENG) and with Anna-Liisa Vasko rejoining the project in 2000, the Helsinki Corpus of British English Dialects (HD) (as the dialectal part of Helsinki Corpus of English Texts was renamed) was completed in 2006. In 2007, the responsibility for the regional English speech project was handed over to Doctor Anna-Liisa Vasko. For more information on the HD, see http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/CoRD/corpora/Dialects/index.html.

The aim of the Helsinki dialect project was to collect a corpus consisting of a substantial amount of continuous spontaneous speech to provide material for the study of dialect syntax, and thus to supplement the Leeds Survey of English Dialects (SED), which focuses mainly on phonological and lexical data. The SED influence on the Helsinki dialect project was especially evident in the preparatory stages of fieldwork, as “the principles for the sampling process were to some extent based on the SED criteria for the selection of localities and informants” (for a more detailed discussion of the selection criteria, see Vasko (2005: 38) and http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/CoRD/corpora/Dialects/fieldwork.html). However, whereas the SED relied on questionnaires to elicit the data, the informal interview method was favoured in the Helsinki dialect project. Dialect is spoken in spontaneous conversation with family, friends and peers. This is why free conversation was considered the most suitable method of recording dialect, especially since the formality of a questionnaire and the influence of the interviewer’s questions might reduce the likelihood of recording long stretches of speech. Uninterrupted continuous speech data are extremely important in syntactic studies, since this kind of analysis requires a relatively large amount of context. The use of the informal interview method rather than “direct elicitation methods” (Ihalainen 1981: 27) or the “directed conversation” type used in the SED recordings to gather Incidental Material (cf. Upton et al. 1994; Kretzschmar 1999) marked a clear departure from the SED. The informants were also encouraged to talk about any topics they pleased, since “[i]f we are to obtain any kind of insight into the structure of everyday spoken language, we need to look at speech where the speaker has selected his own topic which does not emerge as a result of direct questioning” (L. Milroy 1987b: 59).

In order to allow the interview sessions to best reflect a relaxed, “everyday” conversation setting, so-called secondary informants (i.e. people who were not specifically chosen as informants, but were familiar to the primary informant and thus helped make the conversation more “natural”) were often present and permitted to participate in the conversation. The social status of these secondary informants had to be similar to that of the primary informant (Vasko 2005: 50).

The language use of the informant is affected both by the presence of an outsider, or even a local, collecting data for research, and by the presence of recording equipment (see e.g. L. Milroy 1987b: 59). The various concessions – no questionnaires, free choice of topics, presence of peers and using the domestic environment in informants’ homes – were all intended to make the informant comfortable and to create an atmosphere conducive to spontaneous and free conversation, and thus to minimise the effect of the so-called Observer’s Paradox (Labov 1982: 209). (For a more detailed discussion of the Finnish fieldworkers’ data collection methods, see Vasko (2005: 37-61) and http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/CoRD/corpora/Dialects/fieldwork.html.)

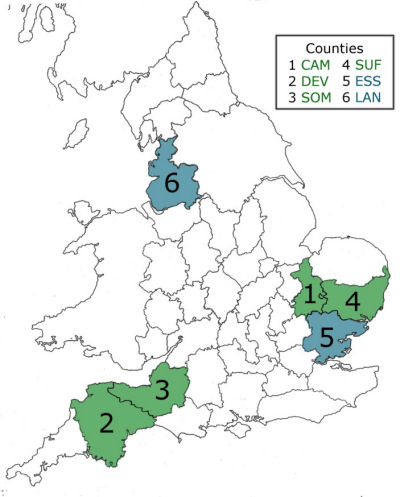

The Finnish students carried out fieldwork in the regions of Cambridgeshire, Devon, Essex, Lancashire, Somerset and Suffolk in the 1970s and 1980s. In Cambridgeshire, Devon, Somerset and Suffolk, the fieldworkers visited a total of 111 rural localities, and in Essex and Lancashire they visited six urban localities. For the regions visited, see Map 1.

Map 1.

For more detailed information on the localities, see the CORD presentation for each region in http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/CoRD/corpora/Dialects/index.html.

In 2007 and 2008, the digitisation of the rest of the original reel-to-reel tapes became possible as a result of funding awarded by the City Centre Campus Online Services, University of Helsinki, to allow this valuable and unique audio data to be preserved for future use. After this digitisation was complete in early 2008, a new project, the Helsinki Archive of Regional English Speech (HARES), was launched. The total length of the HARES audio data is around 211 hours (for details, see Ahava (2010: 51). It was considered more appropriate to create an entirely new corpus, since integrating the digitised audio with the orthographic transcriptions meant that transcription protocols and annotation schemata had to be rewritten from scratch. The HARES team has developed a new orthographic transcription protocol (OTP) for the new corpus, which differs greatly from the one used in the previous projects (for pre-HD transcription examples, see Ihalainen (1980: 187); for transcription principles used in the HD, see the Manual by Peitsara). The OTP used in the HARES was partly inspired by that used in the Newcastle Electronic Corpus of Tyneside English (NECTE; see e.g. Beal et al. (2007b); for the OTP used in the HARES, see Ahava (2010: 59-61)). The major point of difference from the HD came with the implementation of an eXtensible Markup Language (XML) schema for the annotation of the data (for details, see Ahava (2010: 61-65)). For the HARES, see http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/domains/HARES.html.

Although the spontaneous conversation sessions were originally designed to elicit data for the study of dialect syntax, with technological advancements such as audio digitisation and web technologies, the applications of the corpus have multiplied. Throughout the history of both corpora (HD and HARES), the uniqueness of the audio data has remained one of the main driving forces behind the project. The informants give enthusiastic reports about life from the mid-19th century up to the time of the recordings (1970s and 1980s). Their expertise in their chosen professions (e.g. threshing, fishing, turf-cutting, mowing, ditching, cow-milking, ploughing and birding) and “their love for a simpler way of life are reflected in the complexity of their verbal expression” (Ahava 2010: 49, 54). Thus, in addition to the valuable linguistic content, the data provide a unique insight into local history, cultural customs, folk stories and narratives (Ahava & Vasko 2009).

II. The Cambridgeshire Dialect Grammar

The Cambridgeshire Dialect Grammar is an electronic version of Ojanen (1982), my licentiate thesis A Syntax of the Cambridgeshire Dialect, Department of English, University of Helsinki. The thesis is the only monograph-length (266 pages) description of one of the English regional varieties studied by Finnish fieldworkers in the 1970s and 1980s. It was completed before the compilation of the Helsinki Corpus of English Texts: Diachronic and Dialectal (later the Helsinki Corpus of British English Dialects) had even commenced (for details, see I. Regional English speech project at the University of Helsinki). My licentiate thesis was never published and remains, along with the transcriptions and analysis of the 160,000-word corpus of material from 15 localities in Cambridgeshire, the only undertaking of this size and nature by the scholars of the Helsinki Dialect Syntax Group. (See, however, my later study (Vasko 2005), the data of which consist of interviews with 38 informants in 26 localities in Cambridgeshire). I find it relevant and useful to make the material collected for Ojanen (1982) internationally available, since Cambridgeshire has largely remained a blank spot on the dialect map of Britain (for a discussion, see Scarcity of information on Cambridgeshire dialect speech up until the 1970s). Even the comprehensive Leeds Survey contributes little to filling in this blank spot, since its fieldworkers visited only one locality (Elsworth) in southern Cambridgeshire and one locality (Little Downham) in northern Cambridgeshire (historically the Isle of Ely). As late as the 1990s it was possible for Trudgill (1999: 44) to state, “This dialect area is probably one of the least known of all English dialects areas in the sense that few English people have preconceived ideas or stereotypes of what the dialect is like.” The reasons for a lack of interest in Cambridgeshire dialect speech can be condensed into three assertions: (1) Cambridgeshire speech does not differ much from Standard English; (2) Cambridgeshire speech does not differ much from the dialect(s) of its neighbouring counties; and (3) Cambridgeshire speech is similar to Cockney. Although these assertions have a historical basis (for a detailed account on the assertions, see Vasko 2005: 17-26; see also Vasko 2010b), my research has proved them to be invalid. The Cambridgeshire Dialect Grammar seeks to challenge the assumption of close resemblance between Cambridgeshire speech and Standard English/the neighbouring Suffolk and Norfolk dialects and to provide evidence of the fact that the Cambridgeshire dialect also contains its own distinctive features.

The Grammar is a morphosyntactic enquiry into the variety of English spoken in rural Cambridgeshire in the 1970s. It is essentially a synchronic description of the Cambridgeshire dialect. I use the term dialect to refer to a regionally and socially distinctive variety of the English language, identified by a distinctive pronunciation, or accent, and by a particular set of words and grammatical structures (Crystal 2003: 136). Since the Cambridgeshire data were collected using the informal interview method (for details of the method, see Vasko 2005: 37-61; http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/CoRD/corpora/Dialects/fieldwork.html; and the description of the method in I. Regional English speech project at the University of Helsinki), the Cambridgeshire dialect of this Grammar can also be characterised as the variety of English spoken in casual conversation by elderly speakers in Cambridgeshire. Speakers of the Cambridgeshire dialect can also be defined similarly to Ihalainen’s (1980: 187) definition of Somerset dialect speakers: “By calling my informants speakers of the Somerset dialect I simply mean that they were born and bred in Somerset and that their speech shows a number of common features frequently heard in Somerset. Furthermore, those features clearly distinguish my informants’ language from Standard English” (for definitions of Standard English, see the discussion below). Dialects are also referred to as non-standard varieties of a language, as opposed to Standard English, with the difference between these two “closely related to the distinction between written and spoken language” (Kerswill 2006: 34). In this study, the term non-standard is used as a neutral term, with no implication that the dialect investigated ‘lacks standards’ in any linguistic sense.

The Grammar has not been modelled on any particular theory. Rather, the discussion draws on various sources, and the investigations that I refer to include both traditional dialect studies and more recent approaches to the description of particular grammatical features. The starting point of the study is the fact that language is inseparable from human communication. Thus, the Cambridgeshire dialect is approached, described and explained through its users, the informants, and through the constructions which they give form to in their speech.

The Grammar covers the use of verbs, nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs and prepositions typical of the Cambridgeshire dialect as it was recorded in the 1970s in the speech of the 19 informants selected for the study. The comparative framework used in this examination is Standard English, because it is the most widely known English variety. Standard English is the variety which cuts across regional differences, providing a unified means of communication; it is the variety that is printed in media, taught in English language classrooms, and by convention, used for official purposes (e.g. Trudgill 1999: 13). In recent times, this notion has become increasingly complex: differing national standards have emerged with regard to grammar, lexicon, pronunciation and spelling in areas where large numbers of people speak English as their first or second language (cf. e.g. Canadian English and Indian English).

Since the focus of the Grammar is on dialect features, the use of Standard English as a comparative framework facilitates concentration on those aspects of the dialect that makes it distinctive. Since there was (and still is) no one widely accepted grammar of English available – and in particular there is no full and authoritative description of informal spoken English grammar – no single grammar book was chosen as a comparative base (for details, see 2.2).

Great importance is attached to the inclusion of a sufficient amount of illustrative material. In Ojanen (1982), the examples were presented following the transcription principles which were used at the time when the audio material (in the form of reel-to-reel or cassette recordings) corresponding to the examples was not generally available for researchers, and the written transcriptions were the only medium for studying the dialect. Thus, orthographic transcriptions often included representations of certain features of pronunciation typical of the dialect in question. Today, with the audio data generally available (for the audio data of the Grammar, see the discussion of the Cambridgeshire sampler of the HARES in section III), there is no need to illustrate pronunciation features in transcriptions. Thus, in contrast with Ojanen (1982), in this Grammar, the examples are transcribed orthographically according to the principles described in Transcribing Cambridgeshire dialect speech: problems and solutions, without representations of pronunciation, i.e. with no ‘eye dialect’ (see, e.g., Preston (1985), (2000); Macaulay (1991b); Kirk (1997); Beal (2005)).

Naturally, all grammatical features are presented in the form in which they are detected in the informants’ speech. Thus, if the informant utters I’m heard or I knowed him, the transcription has the forms ’m and knowed.

The Grammar has been constructed according to the following principles:

- The text of the Cambridgeshire Dialect Grammar forms the ‘core’ grammar of Cambridgeshire dialect speech. It discusses the grammatical features typical of the Cambridgeshire dialect, comparing the findings with those of other regional dialects from the same and earlier periods. Historical matter has been introduced wherever it seemed to throw light upon the morphosyntactic phenomena and constructions under investigation. The text in this ‘core’ Grammar is preserved mainly in the form presented in Ojanen (1982), with the research terminology of its own time. Alternative grammatical terms are given in brackets and Notes.

- In addition to the text of this ‘core’ Grammar, the work presents findings from studies of the Cambridgeshire dialect and other regional dialects from 1982 onwards. These findings are presented in Notes and in the sections called Additional information and Articles. This solution was chosen as it seemed appropriate to preserve the original ‘core’ Grammar, based on Ojanen (1982), as it was.

- Recently, the study of the grammar of English dialects has been very much on the rise with the arrival of computer corpora, including the Helsinki Archive of Regional English Speech (HARES) and the Helsinki Corpus of British English Dialects (HD). More complete or new findings in specific areas of grammar are therefore referred to in the Notes. These consist of relatively short references to studies dealing with a particular grammatical feature in other regional varieties. The purpose is to give readers information on the studies in which the particular grammatical feature is discussed in greater detail. Another aim is to show the amount of research that has been carried out on a given grammatical feature since the completion of Ojanen (1982). The Notes also include more recent evidence on Cambridgeshire dialect speech, based on a larger amount of material than that in Ojanen (1982).

- As the heading implies, discussions grouped under the heading Additional information include more information on the topics in question. The texts in Additional information are longer than those in Notes. They may present a different viewpoint from that in Ojanen (1982) (e.g. Transcribing Cambridgeshire dialect speech: problems and solutions), or be based on a larger amount of data; they may also examine topics not discussed in Ojanen (1982) (e.g. Characteristics of Cambridgeshire dialect speech).

- The texts presented under the heading Articles are longer than those in Notes or Additional information. They deal with topics not discussed in the Grammar (or Ojanen 1982) (e.g. Scarcity of information on Cambridgeshire speech up until the 1970s) or topics only briefly mentioned in the Grammar (and Ojanen 1982) (e.g. Zero suffix with the third-person singular of the simple present; Male and female language in Cambridgeshire: differences and similarities). These articles are also based on a larger data set than that in the ‘core’ Grammar. They are independent studies and can be read without consulting the Grammar.

This work, i.e. the Grammar with the Notes, Additional information and Articles sections, makes no claim to be a comprehensive account of the morphologic and syntactic phenomena of the Cambridgeshire dialect. A relatively large corpus, such as the one used for this study, will provide ample evidence for studying phonology and, to some extent, morphology, whereas the number of relevant examples for examining a particular syntactic feature remains relatively small. The occurrence of a particular construction in a corpus of continuous free speech is largely dependent on chance, i.e. the topics discussed, and the extent to which an informant is willing to use the construction without guidance from the interviewer (Peitsara 2000: 325).

Naturally, the Notes, Additional information texts and Articles do not include all the research carried out on every single characteristic of dialect grammar. However, in my opinion, they give a fairly comprehensive account of the similarities and differences between the grammatical characteristics of Cambridgeshire dialect speech and those of other dialects for which information is available (or known to the present writer). These Notes and Articles also give an idea of the fields in which the most research has been carried out (e.g. relative clauses, was-were variation, adverbs identical in form to corresponding adjectives, past tense forms corresponding to Standard English irregular verbs, etc.).

During the past few decades, the study of the grammar of English dialects has gained more ground in dialect research (e.g. Trudgill & Chambers 1991a, 1991b; Milroy & Milroy 1993; Kortmann et al. 2005). However, the existing studies often concentrate on a limited number of morphological and syntactic features in the dialect(s) under investigation (with the exception of, for example, Shorrocks 1998-1999). In publishing this Grammar on the morphosyntactic features of the Cambridgeshire dialect, an attempt has been made to give readers a multifaceted and accurate description of the complex character of the “country grammar”, to use the expression of one of my informants.

III. The Cambridgeshire Dialect Grammar and the Cambridgeshire sampler of the HARES

The Cambridgeshire Dialect Grammar is accompanied by the Cambridgeshire sampler of the Helsinki Archive of Regional English Speech (HARES), a collection of transcribed and annotated interviews from Cambridgeshire, including audio data. This sampler (forthcoming in 2010) contains 20 recordings with informants from around the county. Nineteen of these recordings were made during interviews with the informants from this Grammar, based on Ojanen (1982). Material from one more informant was included in the Cambridgeshire sampler of the HARES by drawing on recordings analysed in Vasko (2005).

In addition to the approximately 20-hour sampler of 20 recordings, a selection of illustrative examples in the Grammar is linked with the corresponding audio samples. Thus, it will also be possible to listen to the examples as they were recorded in the interviews with the informants.

|

|