Structure of the Eighteenth-Century English Grammars database

‘English grammar’ in ECEG

The milestone in the field of the eighteenth-century grammatical tradition is Robin C. Alston’s volume I of his Bibliography of the English Language, dedicated to English ‘distinct’ grammars. In the Preface Alston explains that

This volume is devoted exclusively to English grammars written in English by Englishmen, Americans, and in one or two cases foreigners, as well as a very few grammars written in Latin by native speakers. […] the following sorts of books are specifically excluded here: (1) spelling-books containing abstracts of grammar; (2) miscellaneous works, epistolary manuals, &c., containing brief grammars; (3) dictionaries containing grammars; (4) polyglot grammars; (5) grammars of English written in foreign languages, as well as grammars written in Latin by foreigners and published abroad. (Alston 1965: vol. I, xiv)

Bearing in mind that Alston's bibliography, in particular the first volume, has been the starting point of most studies on the eighteenth-century grammatical tradition, it is somewhat expected that previous work might have been biased by his selection of distinct English grammars. It thus follows that English grammars contained in other types of work, such as dictionaries and epistolary manuals, have often been overlooked in the literature, despite being listed in his other volumes (1966–1970). Several research questions arise:

- What was classified as an ‘English grammar’?

- What types of English grammars were included in Volume I?

- What types of English grammars were ‘specifically’ excluded from Volume I, and why?

- Has any (earlier or later) scholar recorded the missing grammars in Alston?

ECEG was constructed in order to answer these and similar questions. Our aim was (i) to revisit Alston’s early bibliographic work beyond Volume I (1965) to include other volumes, supplements and addenda work (1966–2008); (ii) to provide an up-to-date resource for the study of the eighteenth-century grammatical tradition at macro- and micro-level, so that the eighteenth century will no longer be a ‘cinderella’, to use Jones’s (1989) famous words; and (iii) to compile biographical information about the authors of the grammars too, for, as Beal (2004: 90) emphasised, it is only recently that scholars have turned ‘to the original texts and [to] viewing them and their authors in the social and intellectual context of their time’.

Aware of the elasticity and ambiguity of the terms ‘grammar’ and ‘grammar-book’ during the eighteenth century (Sundby et al. 1991: 4-5), we delimited our data to works which fulfil four main criteria so that an ‘English grammar’ in ECEG is a work which (i) deals with morphology and syntax; (ii) is written in English, including those which appear in polyglot grammars when it is evident that the purpose is to teach English, too; (iii) is written by native speakers, with the exception of a small number of ‘naturalized English speakers’ (Sundby et al. 1991: 15); (iv) is printed in the British Isles and, to a lesser extent, the America colonies, again with the exception a couple of foreign places which were consistently quoted in our bibliographic sources.

Crucially for a better understanding of the eighteenth-century grammatical tradition and grammar-writing practices, the scope of the term ‘English grammar’ in ECEG goes beyond the traditional, narrow view of grammar as ‘distinct’ grammar-book. Rather, it also includes subsidiary grammars prefixed to (i) dictionaries or encyclopaedias; (ii) works concerned with the philosophy of the language; (iii) rhetoric and elocution treatises; (iv) letter-writing manuals; (v) polyglot grammars, if written to help them acquire a knowledge of the English language; (vi) spelling-books; and (vii) books of exercises. There is, inevitably, a miscellany category, and we have consulted some manuscripts, too.

Data compilation

In terms of compilation, we resorted to four main groups of reference sources, which have been read, collated and contrasted (sometimes there are inconsistencies and/or disagreements between authors):

- Bibliographies: Kennedy (1927; with addenda and corrigenda by Gabrielson 1929); Alston (1965-2008, vols. I-VIII, Supplement, Addenda); Evans's American bibliography (1903-1959), along with the supplement volume by Bristol (1970).

- Collections, facsimiles and reprints: Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (2006-2010); Evans Digital Collection of American Imprints; Alston's (1967-73) facsimile reprint series English Linguistics 1500-1800.

- Scholarly works: Leonard (1929); Poldauf (1948); Michael (1970, 1987); Vorlat (1975); Sundby et al. (1991); Mitchell (2001).

- Databases and indexes with biographic information: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB online 2004), Lexicon Grammaticorum (Stammerjohann et al. 1996), Universal Index of Biographical Names (Koerner 2008); modern historiographic surveys (e.g. Tieken-Boon van Ostade 1996; Rodríguez-Gil 2002; Cajka 2003; Percy 2003; Sturiale 2006; Navest 2008).

Database entries

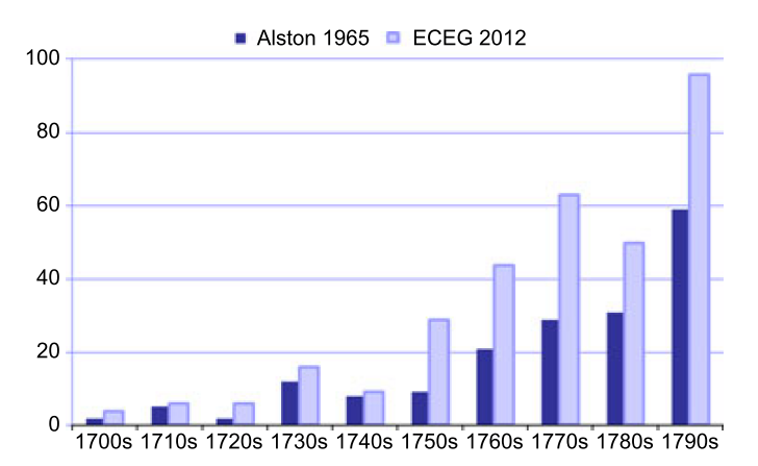

The current version of the database consists of 323 items – English grammars – written by 275 different authors between 1700 and 1800. Figure 1 plots the diachronic distribution of the ‘distinct’ English grammars in Alston (1965) parallel to the number of English grammars in ECEG. Table 1 displays the number of the eighteenth-century grammars compiled from the core reference sources mentioned above.

Table 1. Core reference sources in ECEG (not mutually exclusive).

| Core reference sources |

Items no. |

Items % |

| Bibliographies |

Kennedy 1927 (& Gabrielson 1929) |

150 |

46% |

| Alston 1965 |

190 |

59% |

| Alston 1966-70 |

104 |

32% |

| Alston 1973-74 |

81 |

25% |

| Alston 2008 |

85 |

26% |

| Evans 1903-57 (& Bristol 1970) |

56 |

17% |

| Collections & facsimiles |

Evans digital |

42 |

13% |

| ECCO (2010) |

219 |

68% |

| Alston EL |

40 |

12% |

| Scholarly works |

Leonard 1929 |

49 |

15% |

| Poldauf 1948 |

137 |

42% |

| Michael 1970 |

220 |

68% |

| Vorlat 1975 |

16 |

5% |

| Michael 1987 |

234 |

72% |

| Sundby et al. 1991 |

152 |

47% |

| Mitchell 2001 |

85 |

26% |

| Total |

323 |

100% |

Figure 1. Diachronic distribution of eighteenth-century English grammars in Alston (1965) and ECEG (2012).

Parameters & coding

Each English grammar has been coded in the fullest detail possible in twenty-one different fields, with further sub-classifications, thematically grouped in three major categories: grammars (13), authors (5) and sources (3). Table 2 provides the complete list and a brief description of the sub-fields where relevant.

Table 2. Coding parameters in ECEG.

| |

FIELD |

DESCRIPTION |

| Grammars |

| 1 |

Title |

Full title including printing details. |

| 2 |

Year |

Of the first edition or the earliest edition containing a grammar of English. |

| 3 |

Edition |

First edition or earliest edition containing a grammar of English. |

| 4 |

Editions |

All editions cited in the literature (including editions of copies not located). |

| 5 |

Place of Printing |

Country, County, City. |

| 6 |

Printers |

As in the imprint. |

| 7 |

Booksellers |

As in the imprint. |

| 8 |

Price |

As in the imprint. |

| 9 |

Physical Description |

From catalogues. |

| 10 |

Type of Work |

English (‘distinct’) grammar, Dictionary, Book of exercises, Language, Rhetoric/Elocution treatises, Letter-writing manuals, Polyglot grammars, Spelling Book, Miscellaneous. |

| 11 |

Divisions of Grammar |

Primary contents: Orthography, Orthoepy, Etymology, Syntax, Prosody. |

| 12 |

Subsidiary Contents |

Punctuation, Rhetoric material, Examples of bad English, Examples of handwriting, Snatches of history/geography, Logic, etc. |

| 13 |

Target Audience |

Categories: Age, Gender, Instruction, Specific Purpose.

(Each of these categories comprises a range of different values.) |

| Authors |

| 14 |

Name |

Surname, Forename. |

| 15 |

Gender |

Male, Female, Anonymous. |

| 16 |

Place of Birth |

Country, County, City. |

| 17 |

Occupation |

Books, Education, Politics, Religion, Science, Writing, Other.

(Each of these categories comprises a range of jobs.) |

| 18 |

Biographical details |

e.g. Age, Place of residence, Acquaintances, Other writings. |

| References |

| 19 |

Holding libraries |

Of the first extant edition consulted. (As documented in summer 2010.) |

| 20 |

References |

Literature from which the primary sources have been drawn. |

| 21 |

Comments |

Observations/Corrections from the literature and from our own research. |

References

Alston, Robin C. 1965–1970. A Bibliography of the English Language from the Invention of Printing to the Year 1800. Volumes I‑VIII. Leeds: Arnold & Son.

vol. I, English Grammars Written in English and English Grammars Written in Latin, 1965.

vol. II, Polyglot Dictionaries and Grammars, 1967.

vol. III, Old English, Middle English, Early Modern English, Miscellaneous […] Language in General, 1970.

vol. IV, Spelling Books, 1967.

vol. V, The English Dictionary, 1966.

vol. VI, Rhetoric, Style, Elocution, Prosody, Rhyme, Pronunciation, 1969.

vol. VII, Logic, Philosophy, Epistemology, Universal Language, 1967.

vol. VIII, Treatises on Short‑hand, 1966.

Alston, Robin C. 1967–73. English Linguistics 1500–1800. Facsimile Reprint Series (EL). Menston: Scolar Press.

Alston, Robin C. 1974. A Bibliography of the English Language from the Invention of Printing to the Year 1800: A Corrected Reprint of Volumes I-X, Reproduced from the Author’s Annotated Copy with Corrections and Additions to 1973, Including Cumulative Indices. Ilkley: Janus Press.

Alston, Robin C. 2008. A Bibliography of the English Language from the Invention of Printing to the Year 1800: Addenda and Corrigenda (volumes I-X). Vol. XXI, part 1. London: Smith Settle Yeadon.

Bristol, Roger. P. 1970. Supplement to Charles Evans’s American Bibliography. Charlottesville: Published for the Bibliographical Society of America and the Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia [by] University Press of Virginia.

ECCO = Eighteenth‑Century Collections Online. [Farmington Hills, Michigan.] Gale Group. http://galenet.galegroup.com.

Evans, Charles. 1903–59. American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of all Books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 down to and Including the Year 1820. 14 volumes, with bibliographical notes. [Volume XIII by Shipton; Volume XIV ‘Index’ by Bristol.] Chicago: Privately printed for the author by the Blakely Press (See also Evans Digital Collection).

The Evans Early American Imprint Collection. http://www.lib.umich.edu/tcp/evans/.

Gabrielson, Arvid. 1929. Professor Kennedy’s ‘Bibliography of Writings in English Language’. A Review with a List of Additions and Corrections. Studia Neophilologica 2, 117‑168.

Kennedy, Arthur G. 1927. A Bibliography of Writings on the English Language from the Beginning of Printing to the End of 1922. [Reprint 1961.] Harvard: University Press.

Koerner, E. F. K. 2008. Universal Index of Biographical Names in the Language Sciences. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Leonard, Sterling A. 1929. The Doctrine of Correctness in English Usage 1700–1800. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Michael, Ian. 1970. English Grammatical Categories and the Tradition to 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Michael, Ian. 1987. The Teaching of English from the Sixteenth Century to 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, Linda C. 2001. Grammar Wars. Language as Cultural Battlefield in the 17th‑ and 18th‑century England. Aldershot: Ashgate.

ODNB = Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004. Oxford University Press. Online edition. http://www.oxforddnb.com/.

Poldauf, Ivan. 1948. On the History of Some Problems of English Grammar before 1800. Prague: Prague University.

Stammerjohann, Harro, Sylvain Auroux & James Kerr (eds.). 1996. Lexicon Grammaticorum: Who's Who in the History of World Linguistics. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Sundby, Bertil, Anne Kari Bjørge & Kari E. Haugland. 1991. A Dictionary of English Normative Grammar 1700–1800 (DENG). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Vorlat, Emma 1975. The Development of English Grammatical Theory, 1586–1737, with Special Reference to the Theory of Parts of Speech. Leuven: Leuven University Press. |

|