7 ENGLISH ALONGSIDE THE MOTHER TONGUE

The questions in this section (36–39) aimed at examining the respondents’ attitudes towards mixing the mother tongue with English, and at mapping how often and in what kinds of situations the respondents themselves mix their mother tongue and English in speech and in writing. The questions were motivated by the fact that code switching is a central phenomenon in all language use and in sociolinguistic research (Gardner-Chloros 2009; Auer 1999; Myers-Scotton 1993; Heller 1988).

In Finland, as in other bi-/multilingual contexts/cultures code switching comes in various forms (Piirainen-Marsh 2008; Leppänen 2008; Leppänen et al. 2009b); Finnish–Swedish switching a long-established one. Here we focus on existing and emergent forms of Finnish–English [for Swedish-speaking respondents, Swedish–English] code switching. In other words, Finns use other languages alongside the mother tongue (for the terminology debates between code switching, mixing and other types of alternation, see Auer 1999 and Gardner-Chloros 2009: 10–13). This takes place especially in everyday informal speech situations and in occupational language use. We are especially interested in learning about Finns’ attitudes towards code switching because public debates (see e.g. Hiidenmaa 2003) have long demonstrated concerns that code switching to English may threaten the purity of Finland’s national languages; thus, studying the respondents’ attitudes may shed light on whether Finns’ attitudes towards code switching are as fervent as public debate might suggest.

7.1 Results

7.1.1 Opinions on the mixing of the mother tongue with English

Question 36 presented an imaginary everyday conversation between a married couple, in which there was a mixture of the

respondent’s (officially registered) mother tongue (Finnish or Swedish) and expressions deriving from English, with different degrees of orthographic modification and adaptation into Finnish/Swedish (see questionnaire).1 In 36a the respondents were asked to evaluate on a three-point scale (totally comprehensible, fairly comprehensible, not at all comprehensible) how comprehensible they found this prompt text, i.e. the sample conversation represented in writing. In 36b they were to evaluate on a five-point scale (very positively, fairly positively, rather negatively, very negatively, no opinion) how they reacted to such language use.

In 36a, 86 % of the respondents found the example conversation totally comprehensible. For 11 % it was fairly comprehensible, and only 3 % found it not at all comprehensible. For nearly all the respondents the colloquial expressions originating in English seemed in large measure to be so familiar that they did not cause problems in understanding.

Women (89 %) found the conversation totally comprehensible slightly more frequently than men (83 %). The option fairly

comprehensible was slightly more common among men (13 %) than women (8 %) (Table 36a.1).

Statistically significant differences were found between age groups (Table 36a.2). Over 96 % of respondents under 45 found the conversation totally comprehensible. Among the 45–64 age group the rate was 80 %, but among those aged over 64 it was only 56 %. Interestingly, 88 % of the oldest age group indicated that they found such language totally or fairly comprehensible, even though the respondents in this group had studied English significantly less than the younger age groups. One way or another, English had filtered into their lives as well. However, in this age group, 12 % found the conversation not at all comprehensible while in the younger age groups this option was hardly chosen at all.

Comparisons by area of residence (Table 36a.3) showed that the onversation was found to be more comprehensible in relation to the population of the area of residence: 91 % of city dwellers found the conversation totally comprehensible. In the countryside the rate was lower (75 %) and the proportion of respondents finding the conversation not at all comprehensible was higher than among city dwellers.

Respondents who had not gone beyond primary education differed from the other levels of education – only 40 % of them found the conversation totally comprehensible. Among respondents with the highest levels of education the rate was clearly above 90 % (Table 36a.4). The option not at all comprehensible was chosen by 13 % of the least educated, whereas in other groups the rate was at most a few per cent. The conversation was found easiest to understand by experts, among whom 96 % found it totally comprehensible. This option was chosen least frequently (72 %) by manual workers (Table 36a.5).

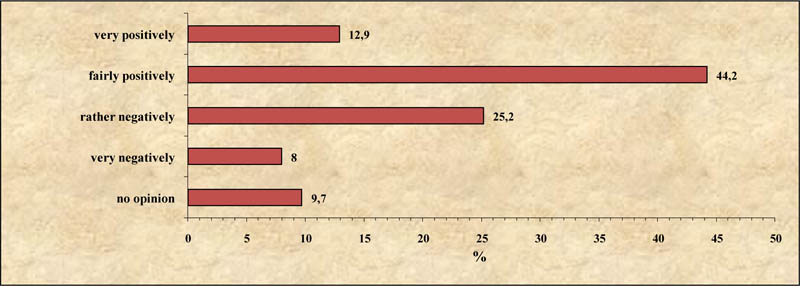

Question 36b inquired how the respondents reacted to language use in which the mother tongue was mixed with English. The response distribution is shown in Figure 46. Overall, positive reactions seemed to be more frequent than negative reactions: more than half of the respondents reacted very positively or fairly positively to the code switching. However, one third reacted negatively.

FIGURE 46 Attitudes to mixing the respondent’s mother tongue and English

Comparisons by background variables are presented in Tables 36b.1–36b.5.

Women (16 %) reacted very positively more often than men (10 %), and men (12 %) answered no opinion more frequently than women (8 %). Otherwise the response distributions were fairly similar (Table 36b.1).

In general, the differences between age groups were such that it was more typical for young respondents to react positively to code switching

(Table 36b.2). The proportion of respondents answering no opinion was highest among the oldest age group (18 %), which perhaps reflects more limited practical experience of code switching. Comparisons by area of residence (Table 36b.3) did not reveal statistically significant differences.

For all levels of education positive reactions to code switching were more frequent than negative reactions, but interestingly, both the

least and the most educated respondents (Table 36b.4) had a more negative attitude than the other educational groups: the proportion of those answering very negatively was higher, and the proportion of those answering very positively was lower than in the other groups (although the proportion of respondents responding with no opinion was significantly high, almost one fifth, among the least educated). It would seem that respondents with the lowest and the highest levels of education are the most critical towards code switching.

Reactions to mixing English and the mother tongue also varied by occupation (Table 36b.5). More frequently than other occupations, it was managers and healthcare workers who reacted very

positively, whereas experts reacted least frequently in this way. Since most experts who participated in the survey were highly educated, this result might further demonstrate a correlation between education and a critical attitude towards code switching. All in all, healthcare workers chose negative options less frequently than other occupations. The option very negatively was most frequently chosen by manual workers, among whom the proportion of respondents answering no opinion was also relatively high.

7.1.2 Mixing the mother tongue and English in speech and writing

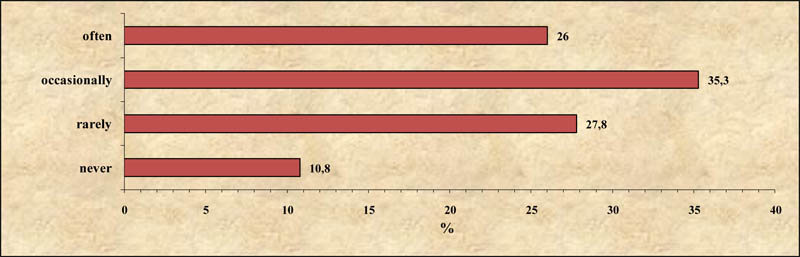

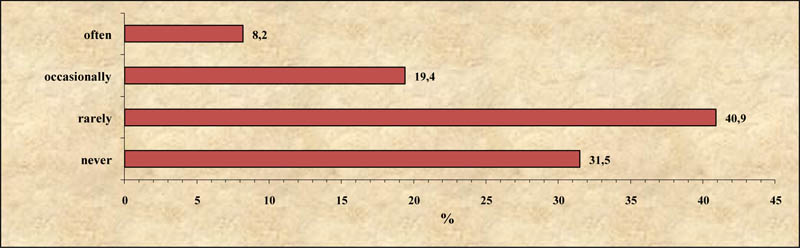

In question 37 respondents were asked to indicate on a four-point scale (often, occasionally, rarely, never) how often they themselves mixed English and their mother tongue in speech (37a) and writing (37b). (Respondents whose mother tongue was English and those who indicated that they did not speak or write English were excluded.) The response rate (just below 80 %) was lower among the oldest age group and the least educated than among the other groups. The response distributions are shown in Figures 47 and 48. They show that mixing languages is significantly more common in speech than in writing.

Question 37a dealt with mixing the mother tongue and English in speech. The response distributions by different background variables are shown in Tables 37a.1–37a.5. There was no statistically significant difference between the responses of men and women (Table 37a.1). The same applied to occupations, though mixing languages was slightly rarer among manual workers than others (Table 37a.5).

FIGURE 47 Mixing the mother tongue and English when speaking

The differences between age groups (Table 37a.2) were clear, as were the differences between areas of residence (Table 37a.3). Mixing languages

in speech was significantly more common among young respondents than older ones: in the 15–24 age group, 41 % indicated that they mixed English and the mother tongue often, whereas among those aged 65–79 the often rate was only around 7 %. Conversely, 35 % of the oldest age group denied that they mixed languages in their speech, whereas in the two youngest age groups this response was as low as 6 %. Comparisons by area of residence revealed that mixing English and the mother tongue was most frequent in cities (68 % at least occasionally), and least frequent in the countryside (51 %).

Comparisons by level of education revealed that respondents with primary education differed from the rest only in terms of mixing languages less often (Table 37a.4). Here it is worth remembering that this group included many elderly respondents. Highly educated respondents indicated more frequently than the others that they mixed languages. However, among respondents with lower secondary education, often was the most frequently chosen option. This correlates with the high proportion of young respondents in this group: overall, they are accustomed to using English.

Question 37b was about mixing the mother tongue and English in writing. Response distributions by different background

variables are shown in Tables 37b.1–37b.5. There was no significant difference between men and women, even though a slightly higher proportion of women indicated that they mixed English and the mother tongue at least occasionally (Table 37b.1). The differences between age groups

were significant (Table 37b.2), and they reflected the same phenomenon as with speech: younger respondents mix languages more frequently than older respondents.

FIGURE 48 Mixing the mother tongue and English when writing

The differences between areas of residence were statistically highly significant. Mixing English and the mother tongue was more common in cities than elsewhere (Table 37b.3). Among city residents, 32 % indicated that they mixed English and the mother tongue at least occasionally, whereas among respondents from other areas the proportion was 27 % or less. Differences between levels of education were minor (Table 37b.4), but the least educated were distinguished by the high proportion (58 %) of respondents answering never. By contrast, among respondents with a higher level of education the proportion was only around 25–30 %.

An interesting aspect of comparisons by occupation was the proportion of customer service workers answering often (12 %), which was higher than among other occupations. All in all, manual workers were the category with the lowest rate of mixing of the mother tongue and English, but a high proportion of managers (40 %) also indicated that they did not mix languages in their writing at all (Table 37b.5).

7.1.3 With whom respondents mix English and the mother tongue in speech and writing

Question 38 concerned only those respondents who in the previous question (37) had indicated that they mixed their mother tongue and English in their speech or writing at least occasionally. This demarcation screened out a high proportion of elderly (see Table 37a.2) and less educated (see Table 37a.4) respondents. The average (median) number of the respondents was ca. 700 (code switching when speaking) and ca. 350 (code switching when writing).

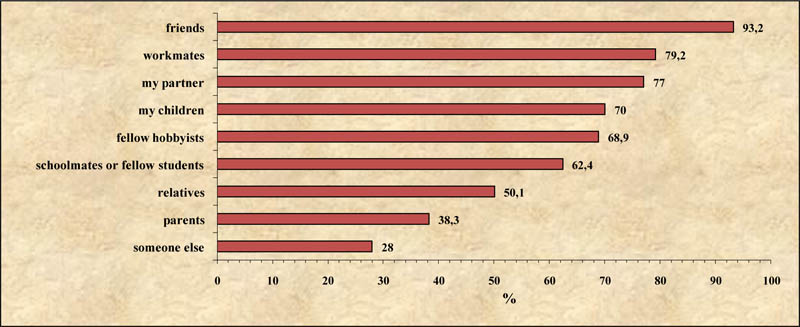

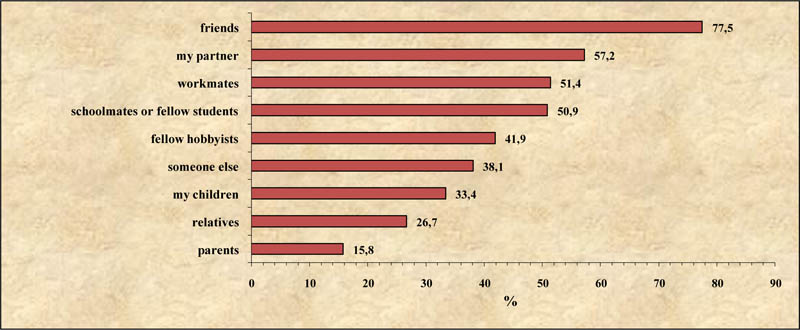

Question 38 asked respondents to indicate their interlocutors/correspondents when they mixed their mother tongue and English. Nine options were given, and the respondents were allowed to choose as many of the options as they wished. The options were my partner, my children, parents, relatives, friends, fellow hobbyists, workmates, schoolmates or fellow students, and someone else, who? For the last option it was possible to add an explanation. The percentages for the options are presented in Figures 49 and 50. In interpreting the results we must emphasise that the percentages have been calculated only for respondents who indicated the option as relevant (by ticking one of the three boxes in a given row rather than leaving the row blank). For example, respondents with no children were excluded from the option my children.

FIGURE 49 The percentages of the respondents who agree with the alternatives given to the question “With whom are you speaking when you mix your mother tongue and English?”

In Figures 49 and 50 the percentages are relatively high due to the exclusions mentioned above. Consequently, the percentages measure how widely the selected respondents – i.e. persons who generally mix languages – mix languages in different contexts. They do not demonstrate the frequencies of context-bound language mixing in the whole population (among whom mixing is significantly rarer, cf. 7.1.2 above). The response rates for question 38 depended on the individual option and on whether speech or writing was being considered.

FIGURE 50 The percentages of the respondents who agree with the alternatives given to the question “With whom are you writing when you mix your mother tongue and English?”

In relation to speech, friends was mentioned by nearly all those (93 %) who answered the question. Frequent also were the options

workmates (79 %) and my partner (77 %), but several other options were almost as frequent (Figure 49). When speaking to parents, only 38 % of the respondents mixed languages. The option someone else, who? was rarely chosen. Foreigners, for example tourists visiting Finland, customers, and partners in co-operation were mentioned as interlocutors in conversations that included language mixing. In speech with foreigners, mixing languages probably means filling out English sentences with words from the mother tongue, whereas in other contexts the situation is probably the opposite.

In writing, too (Figure 50), English and the mother tongue were mixed most with friends (77 % of the responses). Partner (57 %), workmates (51 %), and schoolmates or fellow students (51 %) were also frequently mentioned. The least frequent option was parents (16 %).

Comparisons by gender revealed that men, significantly more often than women, mix languages with fellow hobbyists, whereas women mix languages when speaking or writing to their children (Tables 38.1.1 and 38.2.1). In relation to writing, men indicated more often than women that they mixed languages with workmates. Otherwise the differences between men and women were minor; for example, friends was clearly the most frequently chosen option among both men and women, and in relation to both speech and writing.

In comparisons by age group it should be noted that the number of respondents aged 65–79 was very small, especially with regard to writing. The differences that were detected are mostly as one would expect: for example, the oldest respondents do not mix languages with

their parents, and the youngest do not mix languages with their children (Tables 38.1.2 and 38.2.2). In relation to both speech and writing, friends was the most frequently mentioned option for all age groups. Among young respondents this was somewhat more common than among older respondents.

Some statistically significant differences were found between areas of residence in relation to code switching in speech (Table 38.1.3). The differences reflect distributions of age and occupation, which are different in cities and in the countryside. On the whole, code switching is more common in towns and in rural centres than in the countryside. This tendency was particularly clear in relation to speech with schoolmates or fellow students, workmates, fellow hobbyists, and my partner. When the respondents were asked about code switching in writing, the only statistically significant difference related to fellow hobbyists (Table 38.2.3): in this context, code switching was more common in cities (48 %) than elsewhere.

With regard to levels of education, only a couple of contexts showed statistically significant differences (Tables 38.1.4 and 38.2.4). Again, it should be noted that there were few responses from the least educated group. One interesting finding was that, more than other educational groups, university graduates tended to mix the mother tongue with English when interacting with workmates. This applied to both speech and writing.

All occupations other than managers used code switching most frequently with friends, both in speech and writing. In speech, managers also mixed languages most frequently with friends, but in writing, they mentioned the workmates option most frequently. Among experts it was also more frequent than average to mix English and the mother tongue when communicating with workmates (Tables 38.1.5 and 38.2.5). These tendencies reflect the high level of education typical of managers and experts, and the international nature of their work (including work in the knowledge industries).

Regarding the results for speech (Table 38.1.5), we can further note that manual workers appear to mix languages less than others when speaking to friends (even though friends was the most frequently mentioned option among manual workers, 85 %). Parents were emphasised in this group more than in other occupations.

The results for writing revealed a statistically significant difference in the option fellow hobbyists (Table 38.2.5), which was less frequently mentioned by office and customer service workers, and by healthcare workers. This tendency is undoubtedly linked to, but not entirely explained by, the fact that these occupations are dominated by women; fellow hobbyists was one of the options in which men and women differed according to the analysis based on gender alone (see Table 38.2.1).

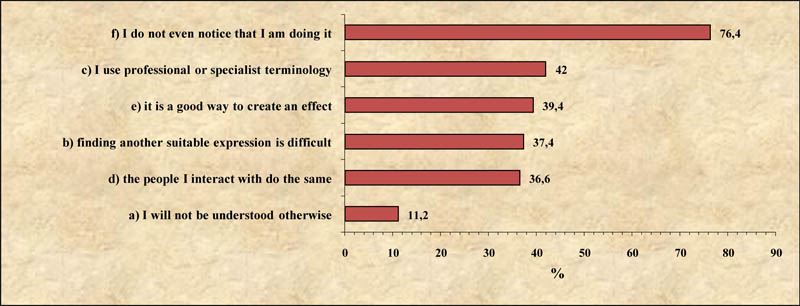

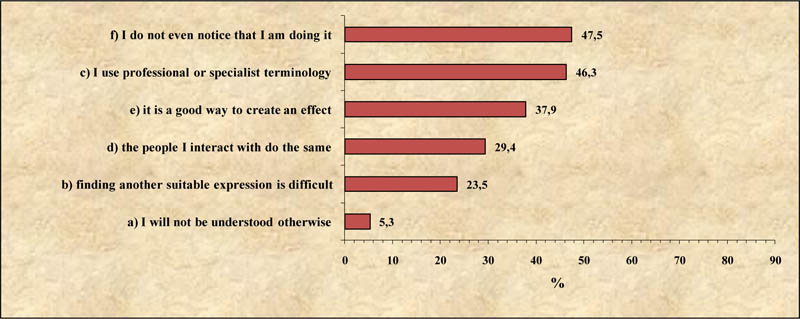

7.1.4 Reasons for mixing the mother tongue and English

Question 39, the last question in this section, aimed at finding out why respondents mix their mother tongue and English when they speak or write. Respondents were allowed to choose one or more of the following options:

(a) I will not be understood otherwise,

(b) finding another suitable expression is difficult,

(c) I use professional or specialist terminology,

(d) the people I interact with do the same,

(e) it is a good way to create an effect,

(f) I do not even notice that I am doing it.

This question was directed only at those respondents who had previously indicated that they mixed their mother tongue and English at least

occasionally. This excluded most of the elderly and less educated respondents. For speech, the number of responses was 966 (approximately 65 % of the total number of respondents), and for writing 492 (approximately 33 % of the total number of respondents).

Both for speech and writing, the most frequently mentioned reason for mixing languages was (f) I do not even notice that I am doing it (Figures 51 and 52). This, too, seems to suggest that English expressions have become a fairly natural part of Finns’ everyday language use, even if this may appear paradoxical at first, as the reliability of the conscious reflection of one’s linguistic behaviour is questionnable (cf. Blommaert & Jie 2010: 2–3; Gardner-Chloros 2009: 14–16). As regards speech, this had a fairly clear lead over the other options, but as regards writing, the use of (c) professional or specialist terminology was almost as frequent as a failure to notice the code switch, i.e. option (f). The least frequently mentioned option, for both speech and writing, was (a) I will not be understood otherwise. This would suggest that code switching is more a means of self-expression than a way to ensure intelligibility.

FIGURE 51 The percentages of the respondents who agree with the alternatives given to the question “Why do you mix mother tongue and English when speaking?”

FIGURE 52 The percentages of the respondents who agree with the alternatives given to the question “Why do you mix mother tongue and English when writing?”

Response distributions by gender are presented in Tables 39.1.1 and 39.2.1. The most obvious difference was found to be the use of (c) professional or specialist terminology; this was more common among men, both in speech and writing. As regards speech, men felt significantly more often than women that (a) they would not be understood otherwise; by contrast, women indicated significantly more often that (b) they could not find another suitable expression.

Differences between age groups varied, depending on the option. More statistically significant differences were found concerning speech

(Table 39.1.2) than writing (Table 39.2.2), possibly due to the fact that mixing languages is less common in writing. In relation to

mixing languages in speech, option (f) I do not even notice that I am doing it was the most frequently mentioned reason in all age groups. However, there was an interesting contrast, in that among the two youngest age groups this option was chosen by over 80 %, whereas in the older age groups the proportion was around 65 %. In addition, the 15–24 age group indicated more mixing (relative to other age groups) motivated by options (e) it is a good way to create an effect (46 %) and (b) finding another suitable expression is difficult (50 %). The notion of code switching being a good way to create an effect tended to become rarer as the age groups progressed.

Persons aged 25–44 differed in that they chose option (c) I use professional or specialist terminology as the reason for mixing languages more often (49 %) than the others. It seems as if young adults at work have a particular tendency to use a specialist jargon that includes English expressions. They also chose option (a) I will not be understood otherwise less frequently (7 %) than the others. As regards writing, statistically significant differences between age groups were found for only two options: respondents aged 15–24 chose option (b) finding another suitable expression is difficult more frequently than older respondents, and those aged 45–64 indicated less frequently than the others that they mixed languages (f) without noticing it. Here it is worth noticing that there were only seven respondents aged 65–79.

In connection with mixing languages in speech, the only statistically significant difference between areas of residence related to option (a) I will not be understood otherwise (Table 39.1.3). This option suggests that code switching is not merely an additional resource in communication or a stylistic device, but that it also relates to becoming understood in situations in which the mother tongue is not sufficient. In this regard code switching is more frequent the more rural one’s place of residence happens to be: only 9 % of city dwellers chose this option, whereas 18 % of country dwellers chose it.

For writing, comparisons by area of residence (Table 39.2.3) revealed a

statistically significant difference in option (c) I use professional or specialist terminology: 52 % of city residents indicated this as a reason for code switching, whereas less than half of the respondents from other areas responded in this way. Residents of rural centres differed in this respect, since only 33 % of them mentioned this as a reason for code switching. More than half of them indicated that they code-switched (f) without noticing it. As regards speech, too, there was a difference between city residents and others in the use of professional or specialist terminology. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

The level of education clearly correlated with the reasons for mixing languages, especially with regard to speech (Table 39.1.4). Reason (c) using professional or specialist terminology, becomes steadily more frequent along with progression from the lowest level of education to the highest. This was the option that most clearly divided levels of education, and it applied to both speech and writing (Table 39.2.4). A contrary tendency emerged concerning speech in option (a) I will not be understood otherwise: choosing this option was less frequent as the level of education progressed. As regards speech, the most frequently chosen option for all levels of education was (f) I do not even notice that I am doing it. However, this occurred less frequently among the least educated (53 %), whereas among the others this reason was chosen by over 70 %. In relation to written language, the least educated group mentioned this option less frequently than the other groups. However, this group is small, and no firm conclusions can be drawn from the percentages in this regard. In relation to writing, the highly educated groups differed from the rest in that their most frequent reason for mixing languages was (c) I use professional or specialist terminology; this option was chosen even more frequently than option (f) (i.e. code switching without noticing it). In speech, these groups were less likely than the others to regard mixing languages as a good way to make an effect.

Using professional or specialist terminology was the factor that divided occupations most clearly (Tables 39.1.5 and 39.2.5): more frequently than the others, experts and managers indicated this as a reason for mixing languages, both in speech and in writing. This was mentioned less frequently by healthcare workers, among whom mixing languages happens (f) without noticing it more frequently than among other occupations (this option was chosen by 93 % of healthcare workers with regard to speech, and by 70 % even in relation to writing). In addition, healthcare workers and manual workers considered more frequently than others that mixing languages in speech (e) is a good way to create an effect. Option (a) I will not be understood otherwise was generally mentioned fairly infrequently, but in relation to speech it was chosen somewhat more frequently (15 %) by office and customer service workers than by other occupations.

7.2 Summary and discussion

The majority of the respondents had good comprehension of the prompt text exemplifying code switching, although there were differences according to gender, age, education, occupation, and area of residence. Even in the oldest age group, slightly more than half of the respondents found the text totally comprehensible, and among countryside residents the proportion was more than 60 %. Among these respondents, English expressions are not viewed as foreign elements, but they rather form a natural part of language use. At the same time we must bear in mind that there were also many respondents for whom the text was not comprehensible at all: these respondents are found among the oldest age group, country dwellers, manual workers, and especially the least educated.

More than half of the respondents reacted positively to code switching, whereas one third reacted negatively. Young respondents had the

most positive attitude towards code switching. Respondents with the highest and lowest level of education were the most critical of code switching, but probably for different reasons. Highly educated persons may be motivated by concerns about the purity of the mother tongue, whereas those with less education may not necessarily have been in contact with or have their own experience of code switching. Despite the strong and polemical views presented in public debate on the use of English, including its effects, and the threat posed by the unwarranted mixing of languages, it would appear that the majority of Finns react to the scenarios presented fairly calmly, even though they do have concerns on the issue.

In speech, English and the mother tongue are reportedly mixed quite frequently; one quarter of the respondents indicated that they did this often. Young respondents are the most active in code switching. Only 11 % of the respondents indicated that it was something they never did – most of these consisting of persons who were less educated, elderly, or living in the country. In writing, code switching takes place much less frequently: one third of the respondents indicated that they did not do this when they were writing. The infrequency of code switching in text as compared to code switching in the spoken language can be explained by the fact that monolingual norms regulate written genres and registers more strongly than, for example, everyday conversation. In addition, producing text is likely to require more planning in advance than producing speech. This planning is also more likely to involve orientation to various monolingual normativities.

Code switching seems to be more typical of young respondents, respondents with a high social status, and city residents than of other groups. Among these respondents English appears to be a more natural linguistic resource than it is to others, and hence, perhaps, adopted more easily and with less conscious awareness. It may be that among young people in particular, code switching involving English is one defining characteristic of their language use. Code switching can therefore have a role as a means of expressing aspects of their identity.

Languages are mixed most when communicating with friends, one’s partner, and one’s peers – most probably in highly informal everyday situations. Among men in particular, code switching also takes place when communicating with fellow hobbyists. It is interesting to observe that highly educated persons and experts code switch when talking to their colleagues. This aspect is probably linked to the requirements for expertise and internationalisation in their work, but perhaps also reflects the good English skills they have achieved in the course of their education.

Particularly in speech, mixing English and the mother tongue occurs mostly without the speaker noticing it (especially among young people). As regards writing, the explanation was almost as frequently the use of professional or specialist terminology (especially among the well educated). Of course, there are other reasons as well. Among young respondents, English expressions function as a means of self-expression and as a stylistic device. In this respect it is interesting that becoming understood is the rarest reason for code switching. Thus, English is useful but not necessary for intelligibility in communication, the mother tongue is sufficient for that. However, English expressions can rather be useful as resources for creating social and cultural meanings.

For the time being, code switching involving English seems to be a linguistic resource mainly for young people and the well educated, and in working life. It can function as a means of creating or maintaining social and cultural identity or expertise. Attitudes towards it are mainly neutral, but to some Finns it is still a foreign phenomenon, and one that raises concern. The reasons for concern might arise from different sources such as insufficient English skills, a wish to preserve the purity of the mother tongue, or an opinion of code switching/mixing as “vulgar” or “banal”.

Notes

1 The example demonstrates a typical everyday speech situation which includes code switching with English. Code switching in this prompt occurs mainly on the level of vocabulary. It includes loan words, some of which are established, used in, and accommodated to spoken Finnish and Swedish (e.g. fiilis ‘feeling’ and jess ‘yes’), and some of which occur more clearly in their English form (e.g. by the way). In reality, these can be phonologically modified to various degrees. Orthography, of course, here represents phonological modification, as the text type is “imagined” reported speech. We are aware that this prompt, at best, can only stand for a small part of all possible Finnish/Swedish–English code switching that actually occurs in our spoken, written, and multimodal realities.

Back to top

|