8 THE FUTURE OF ENGLISH IN FINLAND

In public debate both internationally and in Finland, English is often seen as a threat (e.g. Clampitt-Dunlap 2000; Albert 2001; Phillipson 2003; Skutnabb-Kangas 2003), with the potential to displace the national languages at least in some domains (for example in trade and science) (Hiidenmaa 2003). However, English skills are considered useful in an era of globalisation. And even though the status of English as a global language is currently on a firm footing, the future of English cannot be considered self-evident in a rapidly changing world. Graddol (1997) sees the value of constructing future scenarios – thinking in terms of financial and technological changes, and their influence on the English language and its status. In addition, future scenarios are an important element in language policy planning. That is why in this survey too, we wanted to adopt a perspective on the future of English both globally and in Finland. We wanted to find out the views Finns hold on the status of English in Finland in the future, the people who will need to know English, and the areas of life in which it may be used even more than Finnish. The respondents were asked to give opinions on the status of English in Finland in 2027, i.e. twenty years from the time of the survey.

8.1 Results

8.1.1 English as an official language in Finland

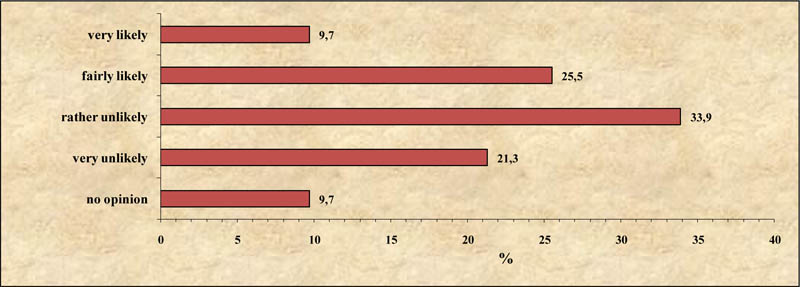

In Question 40 the respondents indicated on a five-point scale (very likely, fairly likely, rather unlikely, very unlikely, no opinion) the likelihood of English becoming one of Finland’s official languages in 20 years’ time (i.e. in 2027). The response distribution is presented in Figure 53. Overall, more than half of the respondents saw this as unlikely (with the options very unlikely and rather unlikely totalling 55 %), although a good third saw it as likely (with the options very likely and fairly likely totalling 35 %).

FIGURE 53 The respondents’ predictions about English becoming one of the official languages in Finland

Only slight differences emerged in comparisons by gender: men (24 %) saw the possibility of English becoming an official language as very

unlikely more frequently than women (19 %). Women chose very likely and no opinion slightly more frequently than men

(Table 40.1). The 64–79 age group found the scenario more likely than the other age groups, but the differences were not great (Table 40.2). However, 15 % of this age group answered with no opinion. The scenario was viewed as most unlikely by the age groups in the middle, i.e. ages 25–44 and 45–64. Some differences were also found between areas of residence: the likelihood of English becoming an official language received the highest rating in the countryside, and the lowest in cities (Table 40.3).

In comparisons by level of education, university-educated respondents showed quite a clear difference from the others. Only 23 % of them

regarded it as very likely or fairly likely that English would become an official language, and as many as 73 % saw this as very unlikely or rather unlikely (Table 40.4). Among all the lower levels of education it was more common to believe that English would gain the status of an official language in Finland. However, among the two least educated groups the proportion of respondents answering no opinion was relatively high (15–18 %). Managers and experts were the category finding the scenario most unlikely, and office and customer service workers the category finding it most likely (Table 40.5).

8.1.2 The position of English in 20 years’ time

In Question 41 the respondents were asked to indicate on a five-point scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly

disagree, no opinion) their reaction to eight statements concerning the importance of English in Finland in 20 years’ time. The statements

were as follows:

(a) the importance of English in Finland will have diminished,

(b) the importance of English in Finland will have increased,

(c) all Finns will need to know English,

(d) there will be more English lessons in basic education than now,

(e) theoretical subjects (such as biology, physics, history) will be taught in English more than now,

(f) vocational and academic education in Finland will be given only in English,

(g) movies and television series will not be subtitled, since people will know English so well,

(h) English will be more visible in the urban Finnish environment than it is now.

To improve the presentation of the results here, the options strongly agree and agree have been merged into

one category (agree), and the results are presented as percentages of the merged category.

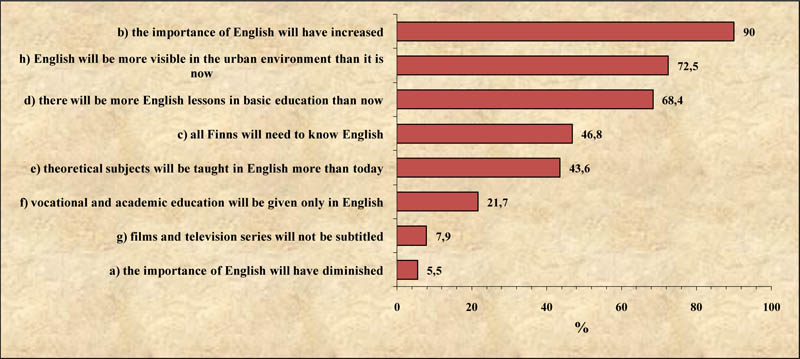

FIGURE 54 The percentages of respondents who agree with the statements about the possible status of English in Finland in 20 years’ time

The percentages of respondents agreeing with the statements are presented in Figure 54. It shows that the great majority of the respondents believe that the importance of English will have increased in 20 years’ time, as proposed in statements (a) and (b). A majority also believed (d) that there would be more English lessons in basic education than currently, and (h) that English would become more visible in the Finnish urban environment. However, more than half of the respondents disagreed with the proposition (c) that all Finns would need to know English. Statements (f) and (g), which predict the mother tongue being totally replaced by English in vocational and academic education, and the end of the subtitling of movies and TV series, were chosen quite rarely. Finns seem to think that the importance of English will continue to increase, but that English will not entirely replace Finnish (or Swedish) in the future.

There were no statistically significant differences between the answers of men and women (Table 41.1). Some statistically significant differences were found between the younger age groups (15–24 and 25–44) and the older age groups (45–64 and 65–79) in their answers to Question 41 (Table 41.2). Younger respondents had a stronger belief in statements (a) and (b) concerning the increasing importance of English, and in (h) concerning the increasing visibility of English in the urban environment. In addition, they expressed more frequently than older respondents the opinion that in 20 years’ time (c) all Finns would need to know English, and that (d) there would be more English lessons in basic education. A similar difference was found concerning statement (g), predicting that films and TV series would no longer be subtitled, though this was a minority view among all age groups. Comparisons by area of residence revealed a clear difference between cities and the countryside: city dwellers had a stronger belief than country dwellers in the increasing importance of English, as predicted by statements (a)–(c), (f), and (h). Towns and rural centres came in the middle, though not altogether systematically (Table 41.3).

Differences between levels of education and also between occupations were statistically significant in relation to almost every statement

(Tables 41.4 and 41.5). Comparisons by level of education showed a tendency for highly educated people to believe more frequently than the others that English would become more important and more widespread. With a few minor exceptions, a similar tendency was found among occupations: the strongest belief in the increasing importance of English was found among managers, experts, and office and customer service workers, whereas healthcare workers and manual workers had the weakest belief in this scenario. Option (d) there will be more English lessons in basic education than now formed an exception, since experts (together with manual workers) were the least likely to agree with this scenario. Similarly, managers were the least likely to agree with option (g) that movies and television series would not be subtitled, since people would know English so well.

8.1.3 English as a replacement for Finnish

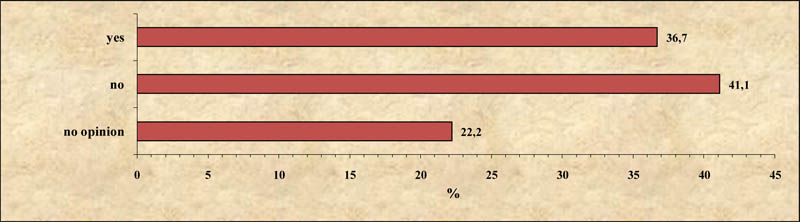

Question 42a asked respondents if they thought English would be used more than Finnish1 in some sectors of Finnish society in 20 years’ time. The options yes, no, and no opinion were given. The response distribution is presented in Figure 55. Responses were fairly evenly distributed between the options yes and no (37 % answered yes; 41 % answered no; 22 % had no opinion).

Men and women differed most clearly as regards the no response: 45 % of men but only 38 % of women gave a negative answer. Women chose the options yes and no opinion more frequently than men (Table 42a.1).

FIGURE 55 The respondents’ predictions about whether in 20 years’ time there will be social domains in Finland where English will be used more than Finnish

Comparisons by age group showed the 25–44 age group as having the strongest belief that the use of English would increase: 46 % answered yes. The smallest proportions of positive answers came from persons aged 65–79 (25 %). The largest proportions of negative answers came from age groups 45–64 (45 %) and 65–79 (46 %). In the youngest age group (15–24) the options yes, no, and no opinion were almost equally frequent, with a proportion of about one third each (Table 42a.2).

The distribution by areas of residence in Question 42a showed in particular that the response patterns of city dwellers differed from those of residents elsewhere (which were broadly similar to each other). In no area of residence was there a huge difference between the proportion of yes and no responses, but cities were the only area in which positive answers (43 %) were given more frequently than negative answers (37 %). In other areas the proportion of positive answers was approximately one third (Table 42a.3).

In relation to respondents answering no, there was not much variation between levels of education, and the proportion was close to 40 % in all groups. However, the proportion of positive answers grew in parallel with the level of education, while at the same time the proportion of respondents answering with no opinion decreased (Table 42a.4).

Among the university-educated respondents, 50 % believed that English language use would increase (as suggested in the question), whereas this was the view of only 16 % of the respondents with primary education only. Conversely, 38 % of the least educated respondents indicated no opinion whereas only 12 % of the university-educated respondents chose this option.

In comparisons by occupation, managers had the strongest belief that the use of English would increase (yes 50 %, no 37 %). In other groups the proportion of positive answers was considerably smaller, the smallest proportion occurring among manual workers (25 %). Among office workers the answers were almost evenly divided between the options yes and no. Approximately one quarter of office workers, healthcare workers, and manual workers answered with no opinion; among managers and experts the proportion was just over 10 % (Table 42a.5).

In Question 42b, respondents who had previously answered yes (= 37 % of all respondents, n = 531) were asked to specify in which sectors they thought English would be used more than Finnish in 20 years’ time. Studies have shown that English is already used more than Finnish in some sectors, for example in science (Taavitsainen & Pahta 2003; Hakulinen et al. 2009); hence it was seen as relevant to study respondents’ views on the sectors within which the same might happen in the future. Eight options were given:

(1) business and financial life,

(2) science (e.g. natural sciences, medicine),

(3) education,

(4) communications,

(5) literature (Finnish authors writing in English),

(6) Finnish rock and pop music,

(7) Finnish web pages,

(8) the subcultures and leisure activities of Finnish young people.

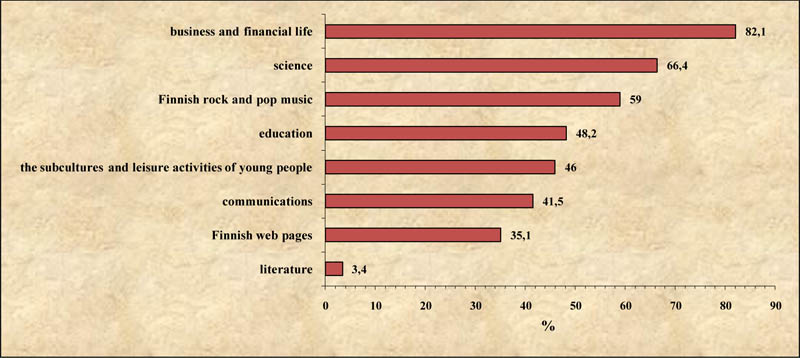

The respondents were allowed to choose several options if they wished. The response distribution is shown in Figure 56. The most frequently chosen option was clearly business and financial life (82 %), followed by science (66 %) and Finnish rock and pop music (59 %); all the options except for literature were chosen to a considerable extent.

FIGURE 56 The respondents’ opinions about the domains in which English will be used more than Finnish in 20 years’ time (the percentages represent the number of positive responses relative to the total population)

Only a few statistically significant differences were found, and none of them occurred between areas of residence (Table 42b.3). Statistically significant differences between the sexes involved only two sectors (Table 42b.1): men believed more frequently than women that English would be used more than Finnish in science (71 % vs. 62 %), whereas women thought the scenario probable in Finnish rock and pop music (63 % vs. 54 %). The only statistically significant difference between age groups involved Finnish web pages. This option was chosen the most frequently by those aged 15–24 (48 %), and the proportion choosing this option decreased quite consistently among the older age groups (Table 42b.2).

Comparisons by level of education revealed statistically significant differences in three of the options (Table 42b.4), i.e. regarding the replacement of Finnish by English in business and financial life, education, and communications. The only systematic tendency that could be discerned in these cases was that university-educated respondents were less likely than the others to consider the scenario probable. Respondents who had completed upper secondary school or vocational education were most likely to believe that language use would change in business/financial life and in education. Respondents with primary education only were most likely to believe that language use would change in communications. Here it should be noted that the group with primary education included only 25 respondents, which is a good deal fewer than in the other groups. This is due to the fact that in Question 42a only 16 % of the least educated respondents saw any likelihood of English replacing Finnish in any sector at all.

Managers and experts (many of whom are likely to have personal experience in the academic world) were the respondents who were most likely to believe that English would replace Finnish in science. This belief was least strongly held by healthcare workers (Table 42b.5). Office and customer service workers were the most likely to envisage that English would be used more than Finnish in education. Experts were the least likely to hold this view.

8.1.4 The need to know different languages in the future

Question 43 asked respondents to choose from three given languages (Finnish, Swedish, and English) the languages they believed particular population/occupation categories would have to know in 20 years’ time. The categories were as follows:

(1) children (under 12 years),

(2) young people,

(3) people of working age,

(4) elderly people,

(5) immigrants,

(6) politicians,

(7) entrepreneurs,

(8) academics,

(9) healthcare and social welfare workers,

(10) journalists,

(11) workers in building and construction,

(12) industrial workers,

(13) public officials and authorities (e.g. the police),

(14) workers in the service sector.

The respondents were asked to indicate their opinion concerning all the categories listed, and to choose several languages if they wished. We

included Finland’s national languages Finnish and Swedish along with English because immigration to Finland (see Pöyhönen 2009: 145–148) has increased during the past decades, with the result that the proportion of inhabitants who know neither English nor Finnish or Swedish is increasing. In addition, public debate on the status of Swedish has been extremely vigorous in recent years.

The results concerning Finnish are presented in Tables 43.1.1–43.1.5. Looking at the data as a whole, over 95 % of the respondents thought that all the population categories should know Finnish in 20 years’ time. Only immigrants (85 % of respondents) and academics (93 % of respondents) received lower rates.

No statistically significant differences were found between men and women. In other comparisons we observed an extremely regular and

statistically significant tendency: the oldest age group gave smaller percentages to every population category. A similar observation emerged in

a few cases when the results were compared by level of education and occupation; here the least educated and manual workers differed from the rest. It is hard to believe that retired respondents would systematically evaluate Finnish skills as less important, compared to other groups. After cross-checking the data we have reason to believe that some of the elderly respondents and manual workers may not have paid much attention in answering the part of question 43 which concerned the need to know Finnish. They could have misinterpreted the question, or else they felt it

to be irrelevant and left it unanswered. However, comparisons by age group gave an interesting and credible result in the case of immigrants:

young respondents were less likely than the others to regard Finnish skills as necessary for immigrants in 20 years’ time (Table 43.1.2).

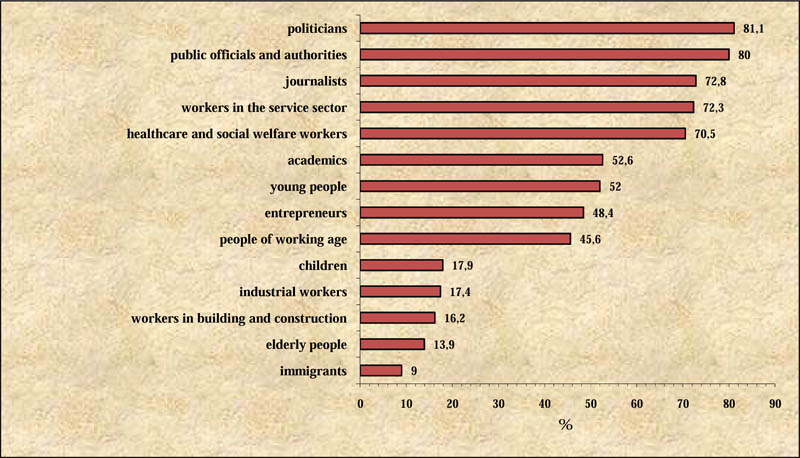

Respondents envisaged Swedish skills as being less necessary than Finnish skills. In addition, the need for Swedish skills was evaluated differently for different population categories, i.e. Swedish was envisaged as necessary for certain groups only. The results are presented in Figure 57.

According to the respondents, there would be a particular need for politicians (81 %), public officials and authorities

(80 %), journalists (73 %), workers in the service sector (70 %), and healthcare and social welfare workers (70 %) to know

Swedish in 2027. The lowest percentages concerned immigrants (9 %) and elderly people (14 %).

Comparisons by gender showed that women, more frequently than men, expected Swedish skills to necessary for all categories, even though the difference was not statistically significant (Table 43.2.1). There were statistically significant differences between age groups concerning several population categories, but the differences and the extent of the differences varied (Table 43.2.2). Respondents aged 15–24 stated more frequently than the others that Swedish skills would be necessary for people of working age, elderly people, and politicians, and less frequently that Swedish would be needed by children, academics, and journalists. These three population categories were also emphasised by the two oldest age groups. In addition, respondents aged 65–79 considered more frequently than the others that Swedish skills would be necessary for immigrants, entrepreneurs, and industrial workers.

FIGURE 57 The respondents’ opinions whether different groups should know Swedish in 20 years’ time (the percentages represent the number of positive responses relative to the total population)

Not many differences were found between areas of residence (Table 43.2.3). The predicted need for people of working age to know Swedish produced slightly higher percentages in cities (about 50 %) than in the countryside (about 40 %). The predicted need for Swedish among healthcare and social welfare workers was also rated more highly in cities and towns (over 70 %) than in more rural areas (around 65 %).

Comparisons by level of education revealed statistically significant differences concerning five population groups: elderly people,

entrepreneurs, academics, workers in building and construction, and industrial workers (Table 43.2.4). Surprisingly, concerning the four latter categories, respondents with lower secondary education (many of whom are still at school) were more likely than the others to see Swedish skills as being necessary in 2027. University-educated respondents differed in that they clearly envisaged Swedish skills as necessary for elderly people more frequently than others.

Statistically significant differences between occupations were found with regard to almost all population groups. The differences were minor only with regard to immigrants, public officials and authorities, and workers in the service sector (Table 43.2.5). In general, it was healthcare workers who most frequently predicted Swedish skills as being necessary (these workers being mainly women, cf. Table 43.2.1). Office and customer service workers, too, were more likely than average to see a continuing need for Swedish skills for many of the categories listed (e.g. for young people and politicians). By contrast, managers and manual workers were less likely than the other occupations to see a continuing need for Swedish skills.

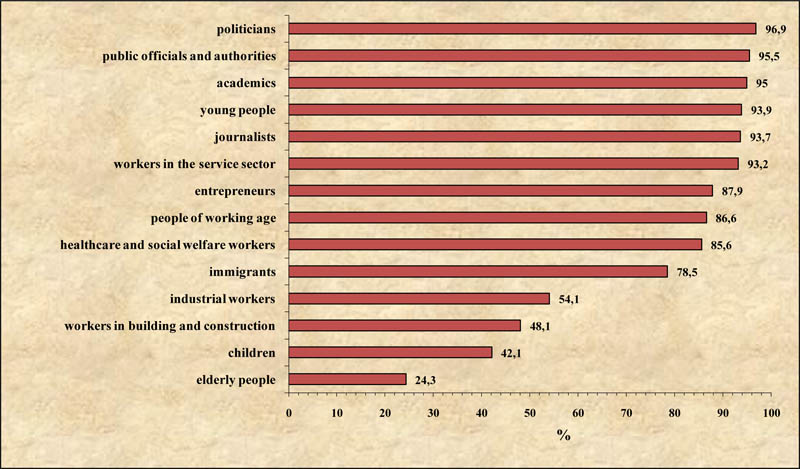

Overall, knowing English was predicted to be a good deal more important than knowing Swedish. Figure 58 presents the percentages for each population category listed. A substantial majority (78 % or more) of the respondents saw English as being necessary for almost every population category. However, this was not the case concerning elderly people (24 %), children (42 %), workers in building and construction (48 %), and industrial workers (54 %).

For all the categories listed, women were at least as likely as men to envisage English skills as being necessary (Table 43.3.1). The differences between age groups were statistically

significant in the majority of cases (Table 43.3.2). Generally speaking, respondents aged 15–24 and 25–44 had a stronger belief in the future necessity of English than older respondents.

FIGURE 58 The respondents’ opinions whether different groups should know English in 20 years’ time (the percentages represent the number of positive responses relative to the total population)

Differences between areas of residence were found concerning two population categories (people of working age and academics, see Table 43.3.3). In both cases, city residents in particular were more likely to envisage a need for English skills than residents of other areas.

Statistically significant differences between levels of education were found concerning only people of working age and academics (Table 43.3.4): the proportion of respondents predicting a need for English was greatest among the highly educated, and smallest among those with little education, though even in this latter group the vast majority saw English skills as being necessary in the future.

Respondents in different occupations differed in their opinions on whether English would be required from people of working age, elderly people, immigrants, healthcare and social welfare workers, and workers in the service sector (Table 43.3.5). For all these categories it was manual workers who envisaged the least necessity for English. Between the other occupations there were few substantial differences. However, with regard to elderly people, both healthcare workers and manual workers were somewhat less likely than other occupations to foresee a need for English in the future.

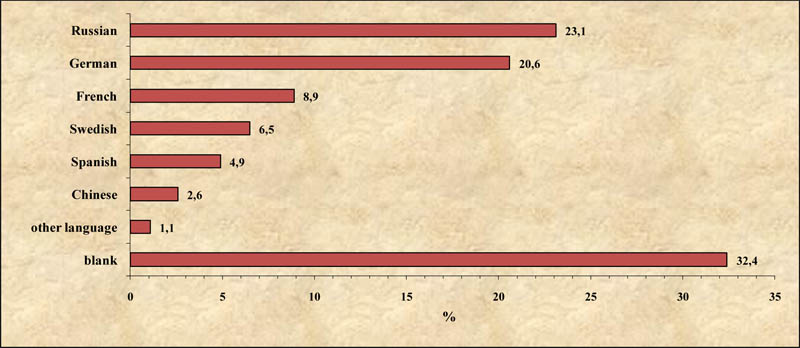

8.1.5 Languages that could challenge English

Question 44 asked respondents to evaluate which other foreign language could in their opinion compete with English for the status of the most important international language in Finland in 2027. Almost one third of the respondents did not mention any language. The most frequently mentioned languages were Russian (23 %) and German (21 %). Less frequently mentioned were French (9 %), Swedish (6 %), Spanish (5 %), and Chinese (3 %). Other languages were mentioned only occasionally, and some of them (e.g. Georgian) were apparently offered as a joke. All in all, the languages that might challenge English were chosen from languages spoken in areas close to Finland and from widely-spoken European languages. Thus, for example, Chinese was rarely mentioned despite being the language of an increasingly important trading power. The response distribution is presented in Figure 59. The main difference between the sexes was that men (26 %) were more likely than women (20 %) to mention Russian, whereas women (11 %) were more likely than men (7 %) to mention French. The overall “popularity ranking” was the same for both sexes (Table 44.1).

In comparisons by age group (Table 44.2) the importance of Russian was emphasised by the 45–64 age group in particular. In all the other age groups German was mentioned more frequently than Russian, though the difference was not great. The youngest age group gave more mentions to French, Swedish, Spanish, and Chinese than did older respondents. The proportion of respondents not answering the question was also smallest in the youngest group.

In comparisons by area of residence (Table 44.3) the popularity of German in particular varied from one area to another. German was least frequently mentioned by city dwellers, who gave Russian clearly higher ratings. In other areas German and Russian were equally popular as challengers to English, and in rural centres German received higher ratings than Russian. However, overall, the differences between Russian and German were not great. French received its highest ratings in the cities, as did Spanish and Chinese. In the cities, Spanish was even seen as more likely than Swedish to be a competitor to English.

FIGURE 59 The foreign languages competing with English in 20 years’ time (the percentages represent the number of positive responses relative to the total population)

In comparisons by level of education, the most highly-educated respondents differed from the rest (Table 44.4). In the group with university education, German was much less frequently mentioned (11 %) than in other groups (where it achieved at least 20 %). Both French and Spanish (around 8 %) came close behind German among the university educated; moreover, Russian (25 %) was rated much more highly than German in this group, and the difference was clearer here than in any other group. German received most mentions (28 %) from respondents with a polytechnic education.

Comparisons by occupation (Table 44.5) reflected a tendency regarding German similar to that observable among university-educated respondents. Both managers and experts mentioned German a good deal less frequently than Russian (German 11–16 %, Russian 22–27 %), and among managers French was rated higher than German, with a percentage of 13 %. Office and customer service workers and especially healthcare workers rated German above Russian as a potential challenger to English. In addition, Swedish was mentioned fairly frequently (12 %) by healthcare workers, almost as frequently as Russian (16 %). Spanish was frequently mentioned by experts and by office and customer service workers.

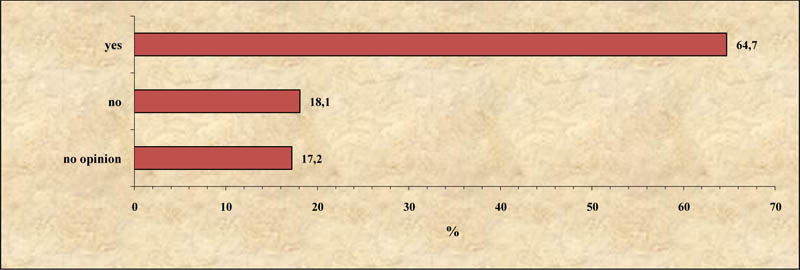

8.1.6 Could ignorance of English lead to exclusion from some areas of life?

Question 45a inquired whether Finns could become outsiders in certain areas of life if they do not know English (without

listing these areas at this point).The options were yes, no, and no opinion. This question was motivated by previous studies

(Latomaa & Nuolijärvi 2002; Leppänen & Pahta, forthcoming; Hakulinen et al. 2009), indicating that English has taken over some areas of Finnish life, and that it is difficult to fully participate in these areas if one does not know English. In this regard one might even see society as being divided into “haves” and “have-nots” (Preisler 2003). From time to time there has been fierce public debate on the topic.

The majority (65 %) of the respondents answered yes, and the remainder of the responses were fairly evenly divided between the

other two options (Figure 60). There was a slight difference between men and women: men chose the option no slightly more frequently

than women, whereas women more commonly chose no opinion. Men and women did not differ in the proportion of respondents answering

yes (Table 45a.1).

The response distributions given by the 15–24 and 45–64 age groups were approximately the same as those occurring in the data as

a whole (presented in Figure 60). By contrast, in the 25–44 age group the proportion of respondents who thought that not knowing English

would involve exclusion from certain areas was clearly higher (72 %, see Table 45a.2). The 65–79 age group held this opinion less frequently (55 %) than the younger age groups. Comparisons by area of residence showed that the notion of potential exclusion due to ignorance of English was held most strongly in the cities (73 %). The proportion of respondents answering yes decreased (and the proportions of no and no opinion increased) as one moved to less urban areas (Table 45a.3).

FIGURE 60 The distribution for the question “In 20 years’ time, do you believe that Finns will have become outsiders in certain areas if they do not know English?”

Comparisons by level of education (Table 45a.4) also showed a consistent tendency: the higher the level of education, the more frequent was the answer yes. Among respondents with a university degree, 87 % indicated that ignorance of English would result in exclusion from certain areas, whereas only 46 % of respondents with no education beyond primary school held this view. A similar pattern was observed in comparisons by occupation (Table 45a.5): yes was chosen most frequently (approximately 75 %) by managers and experts, who usually have a high level of education, and least frequently (52 %) by manual workers, who often have a low level of education. It would seem that the more the respondent has encountered English and had experience of the opportunities and operational environments offered by English, the more likely it is that he or she will envisage the possibility of exclusion due to a lack of English skills.

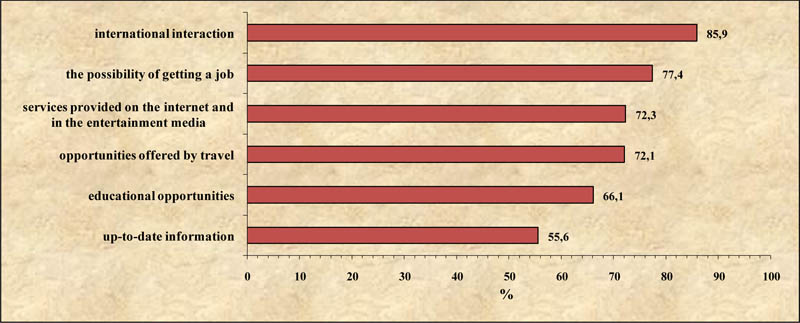

In Question 45b those respondents who had in 45a answered yes were asked to clarify the areas from which (in their opinion) people might be excluded due to a lack of English skills, considering a time frame of 20 years from the present, i.e. the year 2027. The question was thus answered by 65 % (n = 942) of the respondents. Six options were given:

(1) up-to-date information (information is mediated through other channels),

(2) services provided on the internet, and in the entertainment media (e.g. television),

(3) international interaction,

(4) educational opportunities,

(5) the possibility of getting a job,

(6) opportunities offered by travel.

The respondents were allowed to choose several options. The results are presented in Figure 61. All the options were widely supported by the

respondents; the most frequently chosen option was international interaction (86 %) and the least frequently chosen was up-to-date

information (55 %). Integrating the responses from questions 45a and 45b, the majority seem to believe that up-to-date information will continue to be available in the mother tongue in the future.

FIGURE 61 The distribution for the question “If Finns do not know English in 20 years’ time, in what areas will they have become outsiders?”

No statistically significant differences were found between men and women, or between areas of residence (Tables 45b.1 and 45b.3). The two youngest (15–44) and the two oldest (45–79) age groups showed statistically significant differences with regard to the option the possibility of getting a job. This option was chosen by over 80 % of the younger respondents and 70 % of the older. In addition, age group differences approaching statistical significance were found concerning two options, namely services provided on the internet and in the entertainment media and international interaction. These were chosen less frequently by the oldest age group (Table 45b.2).

Statistically significant differences were found between levels of education concerning international interaction, the possibility of

getting a job, and up-to-date information (Table 45b.4). The more educated respondents chose all these options more frequently than the less educated. Becoming excluded from international interaction was chosen by as many as 90 % of respondents with a university or polytechnic degree.

Between occupations, statistically significant differences were found concerning the options the possibility of getting a job and

opportunities offered by travel (Table 45b.5). The possibility of getting a job was given most emphasis by managers, experts, and office and customer service workers (79–84 %), and least emphasis by healthcare workers (66 %). Opportunities offered by travel was mentioned by 81 % of managers. This option was ranked second (78 %) by manual workers. It should also be noted that as many as 95 % of managers opted for international interaction, whereas this proportion had a rating of 90 % or less among the other occupations. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

8.2 Summary

English as Finland’s official language in 2027

The majority of the respondents did not find it very likely that English would become an official language of Finland in the future (i.e. 20 years ahead). This scenario was given the least credibility by city residents, the highly educated, managers, and experts. This may reflect, at least to some extent, that the respondents have positive attitudes to the use of English in education and business (cf. Questions 16 and 17), and the use of English is already commonplace to many Finns – so change is unnecessary. We must note, however, that a substantial proportion of the respondents – more than one third – thought that English would be an official language of Finland in twenty years’ time.

The status of English in Finland in 2027

The vast majority of the respondents believed that in Finland the importance of English would increase in the future. Yet even though the respondents agreed on this, they also did not believe that Finnish would disappear. The respondents did not envisage an entirely English-language vocational or university education to the same extent as they anticipated the spread of English in other respects. The respondents believed and wanted to believe in Finnish/Swedish as language of education in the future, and also that films and TV programmes would continue to be subtitled in Finnish/Swedish in the future. One explanation for this is that Finnish/Swedish subtitles are seen as culturally important. In addition, many Finns seem to feel that the use of subtitles instead of dubbing has played a part in the development of Finns’ language skills and language awareness, and hence that there will be no wish to abandon subtitling in the future.

The respondents were fairly unanimous on the increasing importance of English, but opinions were divided almost evenly as to whether all Finns would have to know English. The spread of English was considered inevitable at least to some extent, but since the respondents also thought that not all Finns would need to know English, it was anticipated that the spread of English would affect different sectors of life in different ways. City residents, persons aged 25–44, and experts had the strongest belief that English would replace Finnish in some sectors. The domains of business and the economy, science, and pop and rock music were presented as areas where English would be used more than Finnish in the future. This presents an interesting contradiction given that respondents also strongly believed that English was not a threat to the languages and culture of Finland (Question 19).

Generally speaking the respondents did not believe in the replacement of Finnish by English, but they did see Finnish as possibly threatened in some areas of language use. Faith in Finnish literature in Finnish and Swedish remains very strong. All this leads one to wonder whether English will come to be used more than Finnish in working and economic life, and in the entertainment industry – areas embodying international aspirations – whereas Finnish will have the function of maintaining the national culture.

Who will need to know English in the future?

A knowledge of English was generally (by at least 90 % of the respondents) expected to be important for nearly all population categories in the future. English skills were not seen as so necessary for elderly people, for children, or for manual workers. The need for English skills was underlined most consistently by respondents under the age of 45. Swedish skills were clearly seen as less necessary than English skills (see Table 19.1). Swedish would be needed in the future mainly by politicians, public officials and journalists, and by certain workers in the health and service sector (see Table 43.2.1). Yet it is also worth noting that the need for young people to have Swedish skills was seen as relatively great, and that this was the opinion of the young people themselves; in fact, more than half of young respondents (aged 15–24) viewed Swedish skills as necessary for young people in the future (see Table 43.2.2). In addition, women seemed to be more positive than men concerning Swedish (Table 43.2.1).

The respondents expected Finnish to remain the most important language for all categories of the population apart from academics: it was believed that academics would need English more than Finnish in the future. This finding supports previous suppositions concerning the possible replacement of Finnish by English in the academic world (Hiidenmaa 2003; Taavitsainen & Pahta 2003).

Within the framework of changes in the linguistic situation in Finland, the significant finding is that the respondents anticipated a very great need for English in 2027 – a need approaching that of the current main language, i.e. Finnish, and clearly surpassing the need for Finland’s second official language, i.e. Swedish.

Languages that could challenge English

The English language was not expected to have very significant competitors in the future. The greatest potential was seen in Russian and German, which had ratings from a good 20 % of the respondents. However, highly educated respondents did not believe in any strong rise in German, considering Russian to be a more likely competitor. Here it is interesting to see how the respondents regarded only languages spoken in areas close to Finland as possible competitors to English. Does this mean that many Finns see international contacts as involving mainly Finland’s geographical vicinity? It is also extremely interesting that Russian was seen as the strongest potential challenger to English, especially in view of the limited extent to which Russian is studied at present (see Statistics Finland 2010a). The infrequent mention of Chinese also seems surprising, even if Chinese was mentioned more frequently among young respondents, city residents, and persons with a university education than among other groups (as was also Spanish). It should also be borne in mind that in a previous question (Question 19) university-educated respondents were of the opinion that Finns should learn languages other than English (see Table 19.4).

Exclusion through ignorance of English?

Two thirds of the respondents believed that people would become excluded in certain areas of life if they did not know English. This was

particularly the opinion of young respondents, city residents, the highly educated, experts, and managers. All the options offered on the areas

of possible exclusion were supported. Yet this is not surprising, since these areas all, in their own way, reflect increasing internationalisation. It seems that those respondents who already have good English skills – and who perhaps have had experience of how these skills have benefited them – think that people will become excluded from certain areas if they do not know English. Up-to-date information is expected to remain available in the mother tongue – but the majority in favour of this view is narrow, with almost half of the respondents feeling that this may cease to be the case in the future. In terms of getting a job, English skills are expected to play a very important role.

All in all, it can be said that Finns believe that the status and importance of English will continue to increase in Finland, even to the extent that it will be used more than Finnish in some areas of life. Many of the respondents also see English skills as likely to be necessary for full participation in Finnish society. Thus, English is associated with a heavy load of ideological and instrumental values, and in this light it is difficult to imagine that there will be any dramatic decrease in the study of English in the future.

Notes

1 In this question, Swedish was not included as Finnish is the dominant language of these domains in Finland.

Back to top

|