4 ENGLISH IN YOUR LIFE

The questions in this section of the questionnaire (13–20) concentrated on what English meant to the respondents, where they encountered English, and their attitudes towards English. We also wanted to know how the respondents viewed English when used by Finns and when used by others.

4.1 Results

4.1.1 Personal significance of English

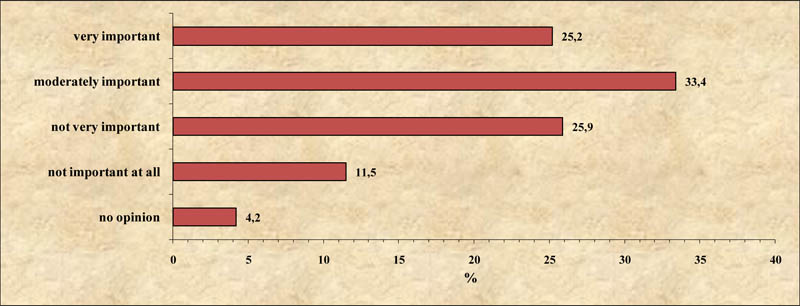

In question 13, the respondents were asked to evaluate on a five-point scale (very important, moderately important, not very important, not important at all, or no opinion) how important English was to them personally (Figure 16). Almost 60 % of the respondents regarded English as at least moderately important. For women, English was slightly more important than it was for men (Table 13.1).

To young respondents English was clearly more important than it was to older respondents (Table 13.2). In the youngest age group almost 80 % regarded English as at least moderately important. Conversely, slightly over 60 % of the oldest age group regarded English as not very important or not important at all. The percentage of no opinion responses was highest in the oldest age group (13 %).

In comparisons by area of residence, English was rated as significantly more important in cities than in the countryside (Table 13.3). In cities, 73 % of the respondents regarded English as very or moderately important to themselves. This proportion decreased from the cities to the countryside, falling to only 36 % in the countryside.

FIGURE 16 The distribution for the question “How important is English to you personally?”

Comparisons by level of education also showed obvious differences (Table 13.4). In particular, the group with the lowest level of education differed from the other groups. As many as 44 % of the respondents in that group saw English as not important at all to them, and only 4 % viewed English as very important. The percentage of respondents answering no opinion was also high (17 %) in this group. The personal significance of English rose with the level of education, so that 57 % of the respondents with a university degree viewed English as very important, and less than one per cent as not important at all. When the answers were classified by occupation (Table 13.5), similar observations were made: in occupations which require a high level of education (managers and experts), English was viewed as more important than in occupations requiring a lower level of education.

4.1.2 English in the respondents’ environment

The aim of Question 14a was to explore where and how often respondents became aware of English as something seen or heard in their own various physical environments. This question was motivated by recent research on “linguistic landscape” (see e.g. Gorter 2006; Shohamy et al. 2010). Research of this kind focuses on the visibility of different languages, particularly in urban environments. It examines how far languages (in this case English) are present in the respondents’ life spheres even if they do not actively use the languages themselves. (Note that encounters with English via various media were explored separately, in Section 6 of the questionnaire.)

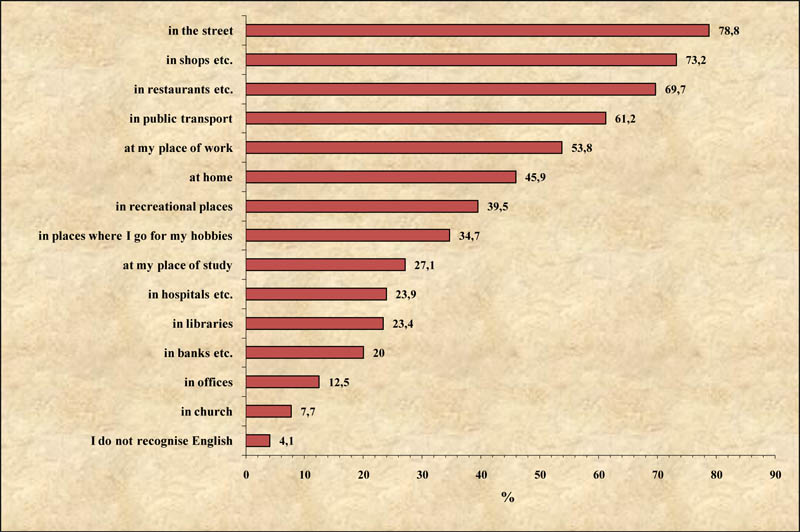

The question listed 14 different places related to everyday life or working life (e.g. place of work, place of study, home, shops and stores, public transport; see Figure 17 and the questionnaire for details). The respondents were asked to indicate whether or not they saw or heard English in the places given as options. Figure 17 shows the percentage of respondents indicating that they saw or heard English in the places listed.

English was seen/heard most frequently in the street (79 %), in shops and stores (73 %), in restaurants and cafés (70 %), and in public transport (61 %). The least frequent places to see/hear English were churches and offices. Accordingly, English mainly appears in the cityscape and in commercial contexts. English does not appear in institutionalised places such as offices or churches, which are clearly places that are more mono- or bilingual (in Finnish or Swedish).

According to question 14a, only 4 % of the respondents did not recognise the English language (cf. question 12 in which approximately 3 % of the respondents indicated that they could not distinguish foreign languages from one another). Most of the respondents recognised English, even if they did not speak it.

FIGURE 17 The frequencies of seeing or hearing English in different places (the percentages represent the number of positive responses relative to the total population)

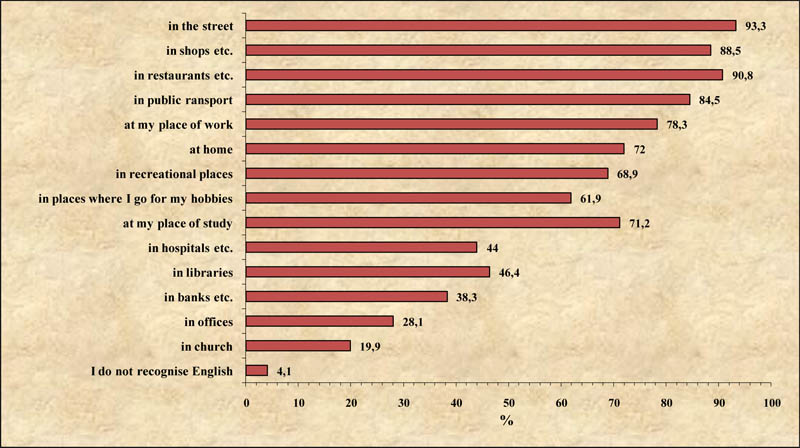

In Figure 17, the statistics are to some extent skewed by the fact that not all the respondents were in working life or studying, or had visited all the places listed in question 14a. In this case nonresponse is equivalent to a negative answer. Overall it appeared that answering question 14a was problematic, and the answers showed a great deal of inconsistency. For the sake of comparison, Figure 18 presents the percentage values calculated by excluding the nonresponse. It shows what proportion of the answers given to a given question were positive. In order to make comparison easier, the categories are presented in the same order as for Figure 17.

FIGURE 18 The frequencies of seeing or hearing English in different places (the percentages represent the number of positive responses relative to the responses in each option)

The modification to the calculation method results in increased proportions of positive responses (Figure 18), but the differences from the previous results are minor. The most notable difference is the increased frequency of the option place of study. The new percentage values demonstrate that 71 % of those for whom the option was relevant (those who were studying) encountered English in their place of study. The percentage of the option libraries also increased more than the average (as compared to Figure 17). This suggests that many of the respondents in our data do not actually visit libraries. Interestingly, 78 % indicated that they saw or heard English at their place of work. This can be regarded as an indication of the proportion of Finns who encounter English in working life.

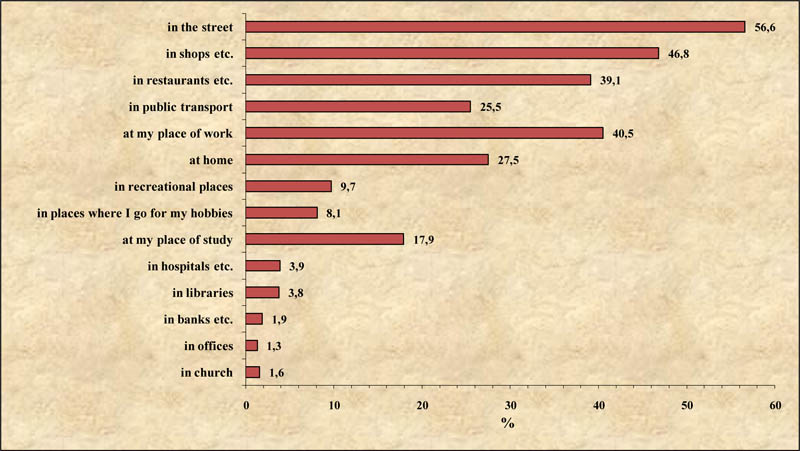

In question 14b the respondents were asked to indicate three places (out of those listed) where they saw or heard English most often. Thus question 14b gives more precise information than is provided by 14a on the key environments where the respondents encountered English. The percentages are shown in Figure 19, and in Tables 14b.1–14b.5. To assist comparison the categories are presented in the same order as in Figure 17.

FIGURE 19 The frequencies of seeing or hearing English in different places (the percentages represent the frequency of each option when it is mentioned among the three most common places where English is encountered)

Even though the phrasing of question was changed, Figure 19 basically gives the same information as Figures 17 and 18. The street is still viewed as the most important place where English is seen and heard. Next come shops and stores, place of work, and restaurants and cafés. In addition, home, public transport, and place of study are viewed as fairly important. Other environments had only minor significance according to question 14b.

The answers to question 14a showed significant differences between the sexes (Table 14a.2). As environments for English encounters, place of work and places for hobbies were emphasised by men, whereas shops and stores, restaurants, recreational places, hospitals, public transport, and churches were emphasised by women. Roughly the same differences between the sexes were found in question 14b (Table 14b.1). These differences seem to reflect the typical differences in the life spheres of men and women.

Comparisons by age group revealed significant differences for all the environments in question 14a, except for church (Table 14a.3). The main observation here is that in all the environments, the oldest age group (65–79) encountered English less than (in particular) the two youngest age groups. In addition, 16 % of the oldest age group indicated that they did not recognise the English language. This rate was 6 % among respondents aged 45–64, and less than 1 % among respondents of a younger age. In question 14b, the most important places for encountering English among the oldest age group were the street, shops and stores, and public transport (Table 14b.2). The answers given by the youngest age group were more evenly distributed between several options. In the 15–24 age group place of study was emphasised (as one would expect), and among respondents of working age place of work and restaurants and cafés were given high ratings.

Comparisons by area of residence (Table 14a.4) show that in almost every case English encounters are most frequent in cities. The differences between towns and the countryside were minor for the most part, with the exceptions of the street, shops and stores, and restaurants and cafés. The only insignificant option was church, where English was rarely encountered. English was most poorly recognised in the countryside (9 % indicating non-recognition), and best recognised in cities (less than 2 % indicating non-recognition).

Question 14b asked where English was most often encountered. The most frequently named location was the street regardless of area of residence (with the exception of the countryside). The street was mentioned by 53–58 % of the respondents, depending on the area of residence (Table 14b.3). In the countryside the most frequent place to encounter English was shops and stores (62 %), with the street coming second (57 %). In towns and rural centres the second most frequently-mentioned environment was shops and stores (48–52 %), but in cities place of work (47 %) came second, after the street. We also noticed that the importance of home as a place where English is seen or heard increased systematically as the focus shifted from the countryside (17 %) to the cities (30 %).

In question 14a, the differences between levels of education were clear in all cases (Table 14a.5). Those who had attended only primary school encountered English least, and those with a higher level education encountered English most, regardless of the environment (the only exception to this pattern was place of study, in which English received quite high responses also from those with only lower secondary education; this is explained by the respondents being still at school, and as yet having no higher qualifications or degrees). One quarter of the respondents in the group with the lowest level of education indicated that they did not recognise the English language. In the other groups the rate was either zero or very low. The answers to question 14b (Table 14b.4) show that along with higher levels of education, the importance of workplace and home as places where English is encountered increases, and the importance of shops and stores decreases. In addition, the respondents with the lowest level of education mentioned banks/post offices/insurance agencies more frequently than others. Respondents with the second lowest level of education (lower secondary school) mentioned place of study, public transport and libraries significantly more often than the others. This too can be explained by the high percentage of respondents still at school in this particular respondent group.

In comparisons by occupation, the extremes appear to consist of experts and manual workers. According to question 14a, experts saw or heard English more than average in almost all environments, and manual workers less than average (Table 14a.6). It is not surprising that healthcare workers mentioned hospitals and offices more frequently than other occupations, and that office workers mentioned banks/post offices/insurance agencies. On the other hand, healthcare workers mentioned workplace and banks/post offices/insurance agencies significantly less frequently than other occupations. In addition, compared to other occupations, managers mentioned libraries very seldom as places where they encountered English. Among manual workers, about 10 % said they did not recognise the English language. Among other occupations the rate was around one or two per cent.

Question 14b resulted in fewer differences between occupations. All the occupations mainly mentioned the same places as the three most important places for encountering English. However, Table 14b.5 shows that among managers and experts the importance of place of work emerged strongly, especially in comparison to healthcare workers. Among healthcare workers, shops and stores and public transport were emphasised in addition to hospitals. This reflects the fact that the caring industry is dominated by women: one can see that the same environments were emphasised among women in comparisons by gender (Table 14b.1). Experts mentioned home more frequently as a place where they saw or heard English, compared to other occupations.

4.1.3 Most and least attractive varieties of English

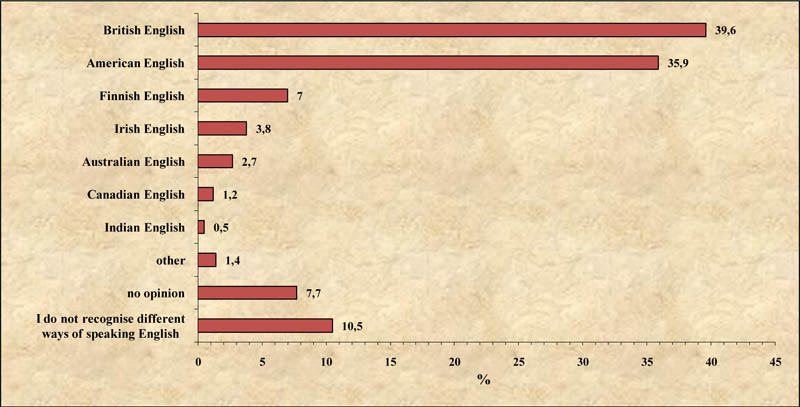

In question 15 the respondents were asked to indicate which of seven varieties of English spoken in different countries (British English, American English, Australian English, Irish English, Canadian English, Indian English, and Finnish English) appealed to them most, and which appealed least. This is an interesting issue since nowadays Finns hear (for example in the media) other English varieties than the traditional British English and American English standard varieties, which are also the ones best represented and respected in language education (see e.g. Pihko 1997; Lintunen 2004). In addition, we were interested in seeing how the respondents viewed other varieties, including Finnish English (the way in which Finns typically use and pronounce English).

In 15a the respondents were asked to select one out of seven varieties given as options (or to indicate some other variety) as the one that appealed to them most. The option no opinion was also given. In 15b the respondents were asked to indicate the variety that appealed least to them. Question 15 was aimed only at those respondents who in 14a indicated that they saw or heard English in some environment. If a respondent felt incapable of recognising different varieties, he/she was told not to answer. These respondents made up 11 % of the total.

The distribution for question 15a is shown in Figure 20. By far the most popular varieties were British English (40 %) and American English (36 %). Thus the varieties that are central in school teaching (and are obviously the most familiar in general) were the ones that seemed to appeal to respondents the most. Preferences for any other variety were extremely rare.

FIGURE 20 The variety of English perceived as the most appealing

The main difference between men and women was that women (48 %) preferred British English and men (41 %) preferred American English (see Table 15a.1). American English was the most appealing variety to 31 % of women, and British English to 31 % of men.

Among the two oldest age groups (Table 15a.2), almost half mentioned

British English as the most appealing variety, whereas in the two youngest age groups American English was the most popular variety (approximately 40 % in both groups). The appeal of American English to young people may be explained by its central role in popular culture. Finnish English was chosen as the most appealing variety somewhat more frequently among the 65–79 age group (12 %). However, one quarter of that age group indicated non-recognition of different varieties of English.

In comparisons by area of residence, the most significant difference was that British English was most popular in the cities (43 %), but lost its popularity in the countryside (29 %), where American English was clearly more popular (43 %). In rural centres, American English was less popular than British English (Table 15a.3). In addition, country dwellers indicated more often than city dwellers that they did not recognise different varieties of English: the “non-recognisers” made up 18 % of the respondents living in the countryside, whereas in cities the percentage was 7 %.

Statistically significant differences were found in comparisons by level of education and occupation (Tables 15a.4–15a.5). The second lowest level of education (lower secondary education) stood out, with American English clearly the most popular variety. In other groups, British English was more or equally appealing. The probable explanation is that in the lower secondary group over 40 % were young people (basically still at school), representing an age group preferring American English to British English. Finnish English was found to be more appealing as educational levels went down (in the least educated group 15 % viewed Finnish English as the most appealing variety). At the same time the ability to recognise different varieties of English decreased. Almost one third of the least educated indicated non-recognition of varieties of English.

Managers and manual workers considered American English more appealing than British English. Among other occupations the situation was the opposite, and experts in particular preferred British English. Finnish English was most appealing to 9 % of healthcare workers and 11 % of manual workers, whereas among other occupations the proportion was significantly lower. Among healthcare workers and manual workers it was also more common not to recognise different varieties. It should also be noted that for this question, among manual workers, 13 % answered no opinion and ca. 20 % left the question unanswered.

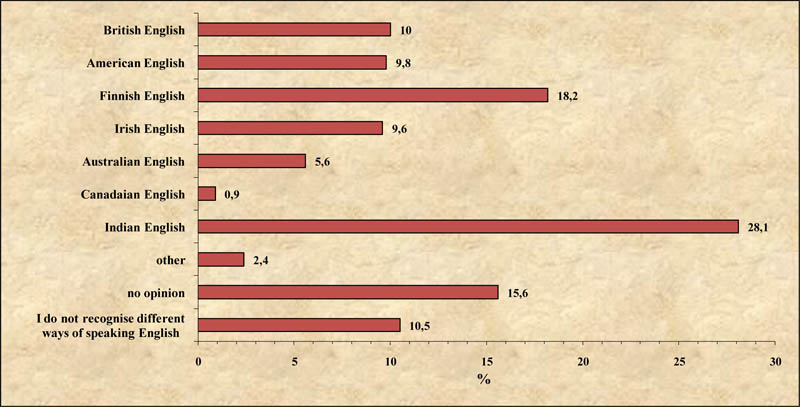

In question 15b the respondents were asked to evaluate which variety of English appealed to them the least (Figure 21). The least appealing variety was Indian English (28 %), and the second least appealing was Finnish English (18 %). For easy comparison of the answers for questions 15a and 15b, the categories in Figure 21 are presented in the same order as in Figure 20. The response distributions were fairly similar for men and women, though women answered no opinion more frequently than men. The distributions were the converse of the earlier finding, according to which women tend to prefer British English, and men American English (Table 15b.1).

The differences between age groups were more significant (Table 15b.2). In the two mid-range age groups (25–44 and 45–64), Indian English was clearly the least appealing variety (14–35 %). The oldest age group found American English (25 %) the least appealing. For the youngest age group, Indian English (25 %) and Finnish English (25 %) were equally the least appealing varieties of English.

Some differences were found in comparisons by area of residence (Table 15b.3). The most unpopular variety in all areas of residence was Indian English and the second most unpopular was Finnish English. In cities Indian English (32 %) was clearly less appealing than Finnish English (17 %), but in towns and in the countryside the unpopularity of Indian English decreased and that of Finnish English increased, so that both varieties were almost equally unpopular (20 %). An interesting result, which lacks any explanation, is that in the countryside British English was mentioned remarkably often (17 %) as the least appealing variety (cf. question 15a, in which the popularity of British English was significantly lower than in other areas of residence). The proportion of respondents answering no opinion was equal in all areas (approximately 15 %).

FIGURE 21 The variety of English perceived as the least appealing

In the results classified by level of education (Table 15b.4), one should note the group of respondents with the lowest level of education. This group found Finnish English (21 %) and American English (19 %) the least appealing varieties of English. The result is at least partly related to the fact that the group includes a high proportion of elderly respondents. Among the other groups, Finnish English (in addition to Indian English) was found to be the least appealing variety. Among respondents with the highest levels of education, Indian English was clearly the least appealing variety. In these groups, British English was seldom mentioned as the least appealing variety. The influence of young respondents, who are still in school, is again seen in the answers of the group with the second lowest level of education: Finnish English emerges as the least appealing variety, whereas American English was mentioned somewhat less often than it was by other groups.

The distributions by occupation (Table 15b.5) also revealed some significant differences. The most significant difference concerned how the respondents viewed Finnish English: managers and experts only rarely viewed it as the least appealing variety (managers 7 %, experts 13 %), whereas among other occupations more than one fifth found it the least appealing. Among managers and experts, Indian English was emphasised as the least appealing variety. In addition, one should note the responses of healthcare workers, of whom a fairly high proportion (21 %) answered no opinion.

Answers to questions 15a and 15b interestingly demonstrate that Finnish English is seldom found appealing. In contrast, British English and American English are appreciated, possibly reflecting the models that Finns are expected to follow. An interesting finding is that opinions on British English and American English are divided: respondents with a high level of education, city dwellers, and older respondents prefer British English, whereas country dwellers and young respondents prefer American English.

It is worth recalling that in this question the response rates in the oldest age group, and also among the respondents with the lowest education level, were the lowest in the whole survey (under 70 %). In addition, the proportion of no opinion responses was relatively high. It seems that the respondents in these groups found it difficult to evaluate or even recognise the varieties of English in question.

4.1.4 Opinions on teaching conducted in English

Question 16 addressed Finns’ views on the use of English in Finnish educational settings, a phenomenon that has increased, especially during the past couple of decades. The background to this question is the popularity of language immersion and English Language Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) methodologies, a trend which developed strongly around the turn of the millennium (see e.g. Nikula & Marsh 1996; Lehti et al. 2006). In public debate the phenomenon has raised concerns, with fears that English language instruction will take up time scheduled for the teaching of the mother tongue, impair learning results, and even affect thinking capacity (see e.g. Virtala 2002; Leppänen & Pahta, forthcoming). Against this background, it is interesting to discover what the general opinion on the issue is.

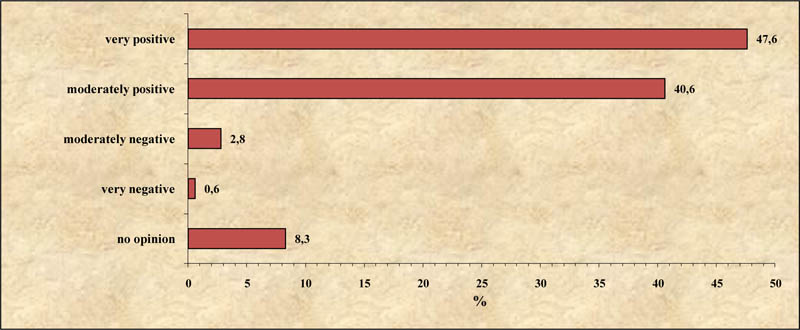

FIGURE 22 Opinions about Finnish children attending English-speaking schools

Respondents were asked for their opinions concerning the fact that some Finnish children attend English-speaking schools. A five-point scale was used (very positive, moderately positive, moderately negative, very negative, or no opinion). The results showed a large majority of Finns with a positive attitude to Finnish children attending English-speaking schools: very positive was indicated by 48 % of the respondents and moderately positive by 41 % (Figure 22).

Gender does not have a great influence on the response distribution, even if the proportion of very positive opinions is higher among

women (50 %) than men (45 %) (see Table 16.1). Comparisons by age group showed that the two mid-range age groups have the most positive opinion on the issue (Table 16.2). In these two age groups half of the respondents viewed the attendance of children at English-speaking schools as very positive. Distributions by area of residence (Table 16.3) showed no statistically significant differences. The results by level of education and occupation (Tables 16.4–16.5) showed the main differences in the no opinion response. This response was highest among respondents with the lowest level of education, and among manual workers.

4.1.5 Opinions on the use of English as the internal language of companies

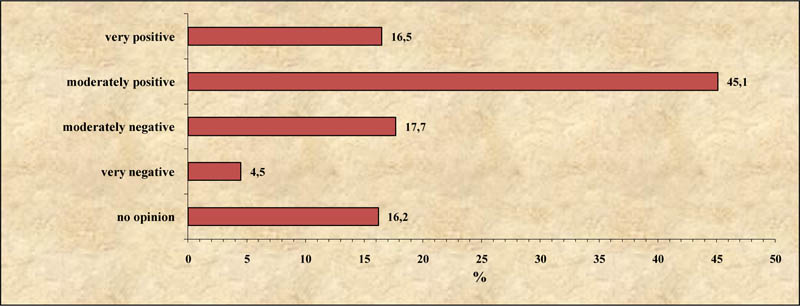

Question 17 asked respondents’ opinion on the use of English as the internal language of some Finnish companies. A five-point scale was used (very positive, moderately positive, moderately negative, very negative, or no opinion). The aim was to explore Finns’ attitudes towards the growing importance of English in Finnish business and working life (see e.g. Virkkula 2008).

FIGURE 23 Opinions about using English as the internal language in Finnish companies

The majority of the respondents had a positive opinion: the total percentage of very positive and moderately positive answers

was 60 %, whereas the corresponding percentage of negative answers was 22 % (Figure 23).

Differences between the sexes were not statistically significant (Table 17.1), but the other background variables showed significant differences (Tables 17.2–17.5). The most positive opinion was found in the 25–44 age group (72 % positive). The 65–79 age group showed a lack of enthusiasm or involvement (no opinion was highest in this group). The highest actual negative response (28 %) came from the 45–64 age group; on the other hand, this same age group came second in the very positive category, so this age group appears to be slightly more bipolar than the others. All in all, there seems to be a clear difference in the attitudes of younger and older respondents of working age (Table 17.2).

In comparisons by area of residence, positive opinions were more frequent in the cities than in the countryside (Table 17.3). The proportion of positive opinions reached almost 70 % among residents of cities, around 60 % among residents of towns and rural centres, and 49 % among country dwellers. The percentages of negative opinions and of respondents answering no opinion were correspondingly higher among country dwellers.

A very positive opinion on Finnish companies’ use of English as their internal language correlated strongly with the respondent’s level of education (Table 17.4). At least a moderately positive opinion was given by 77 % of the respondents with a higher level education. Among respondents with a moderately positive opinion, no great differences were found by level of education, except in the case of respondents with only primary education, who had the least positive opinion (36 %). In addition, a high proportion (39 %) of respondents in this group were unable to give an opinion on the subject. Comparisons by occupation (Table 17.5) offer similar information: the proportion of very positive opinion was highest among managers (27 %) and experts (25 %). No significant differences were found among respondents with moderately positive or moderately negative opinions, but the proportion of no opinion responses was highest among healthcare workers and manual workers (24 % in each case).

4.1.6 Opinions on Finns’ efforts when speaking English

Question 18 was in three parts. It asked about respondents’ feelings when they hear a famous Finn speaking English on TV or on the radio. Question 18a concerned non-fluent speech, question 18b concerned fluent speech with a Finnish accent, while 18c concerned native-like fluency. In questions 18a and 18c the respondents were offered seven options (see Figures 24 and 26, and questionnaire). In 18b they were offered nine options (see Figure 25 and questionnaire).

In Question 18, the notion of a “famous Finn” was chosen because the English skills of public figures have often inspired critical public commentary, for example in letters to the editor and in discussion forums on the internet (see Kytölä 2008). Opinions on the language use of public figures are likely to reflect more general language attitudes. As the answers to question 15 already indicated, Finns do not seem to value their own way of speaking and pronouncing English, finding it in some way problematic. Question 18 offers more specific information on respondents’ reactions to Finns’ use of English.

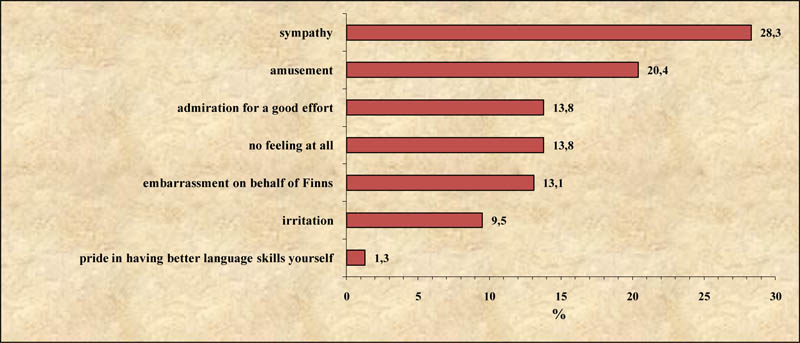

FIGURE 24 Attitudes to hearing a famous Finn speaking English poorly

Opinions on the non-fluent English speech of a Finn (question 18a) varied greatly: most frequently the respondents felt sympathy (28 %), but other feelings were also common (Figure 24). Approximately 14 % of the respondents said that a Finn speaking English poorly in public aroused no feeling at all. Women felt sympathy, admiration for a good effort, and embarrassment on behalf of Finns more often than men, whereas men felt amusement and irritation more often than women (Table 18a.1).

With regard to age groups (Table 18a.2), the two oldest groups (45–64 and 65–79) had more sympathy and admiration for a good effort than the younger age groups. In addition, one fifth of the oldest age group said that speaking English poorly aroused no feeling at all. In the youngest age group (15–24) it was common to feel amusement and embarrassment on behalf of Finns. Sympathy was felt significantly less in the youngest age group than in other age groups. It may be that among older respondents even the bare attempt to speak English is admired, whereas among younger respondents the general attitude is that English should be mastered fairly well if it is spoken in public. This implies that English skills are not taken for granted by older respondents in the same way as they are by younger age groups.

No statistically significant differences were detected between areas of residence (Table 18a.3). Comparisons by the other background variables (Tables 18a.4–18.a.5) showed that feeling sympathy was felt more as the level of education increased. The same phenomenon was detected among occupations requiring a high education, e.g. experts. Among those with the lowest level of education, 29 % had no feeling at all when they heard a Finn speaking English poorly. This was also common among manual workers. Healthcare workers were distinct among occupations in that on the one hand they felt admiration for a good effort more than the others, but on the other hand embarrassment on behalf of Finns less than the others.

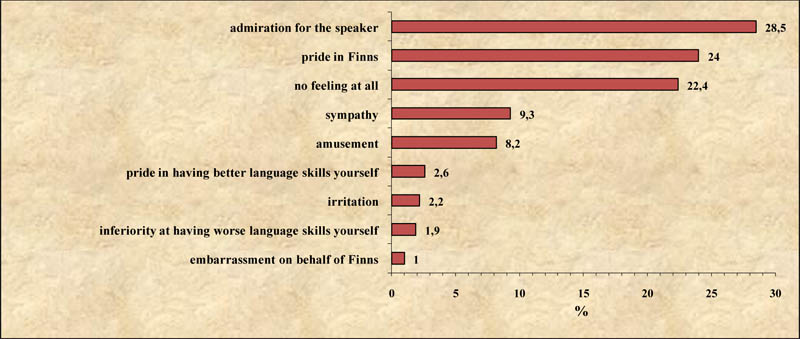

The most common reaction to a Finn speaking English fluently but with a Finnish accent (question 18b) was admiration (29 %) and pride in Finns (24 %) (Figure 25). The proportion of women having these opinions was higher than the proportion of men (Table 18b.1). Feeling admiration and sympathy was more typical of older than of younger respondents, whereas younger respondents more often felt pride in Finns or amusement, or else no feeling at all (Table 18b.2).

FIGURE 25 Attitudes to hearing a famous Finn speaking English fluently with a Finnish accent

Comparisons by level of education and occupation did not show statistically significant differences (Tables 18b.4 and 18b.5). Differences between areas of residence appeared minor (Table 18b.3), but we noticed that admiration for the speaker was more common in the countryside than in the cities. In all areas of residence a substantial proportion (18–25 %) of respondents said they had no feeling at all when they heard a Finn speaking English fluently but with a Finnish accent. The results indicate that fluency is to some extent more important than a native-like accent.

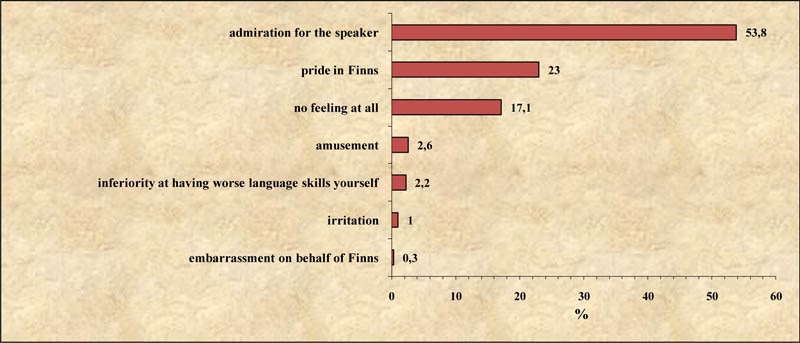

A Finn speaking English like a native speaker of English (question 18c) gained a strong positive response: the most common feeling was clearly admiration for the speaker (54 %) (Figure 26). No statistically significant differences were found between age groups (Table 18c.2). However, women felt admiration for the speaker and pride in Finns slightly more than men, whereas men indicated no feeling at all more often than women (Table 18c.1). There were no statistically significant differences between areas of residence (Table 18c.3). Having no feeling at all was most common among respondents with the lowest level of education (30 %) and manual workers (27 %), whereas admiration for the speaker was felt less frequently among these groups (Tables 18c.4–18c.5). Admiring a speaker who sounded like a native speaker was most common among those with a university education, and among experts.

FIGURE 26 Attitudes to hearing a famous Finn speaking English like a native speaker

4.1.7 The importance of English in Finland

Questions 19 and 20 addressed the respondents’ attitudes towards English in Finland and elsewhere. The questions are motivated by the undeniably strong global position of English: more than 500 million people speak it as their first or second language, approximately one fifth of the world’s population speak it to a varying extent, and a growing number among the rest want to learn it (Graddol 1997, 2006). The exceptional status of English – and its expansion in the world – has been seen as both a positive (Crystal 1997) and a negative phenomenon (Skutnabb-Kangas 2003; Phillipson 1992), and it also has contributed to polarised language attitudes in Finland (for details see Leppänen & Nikula 2008).

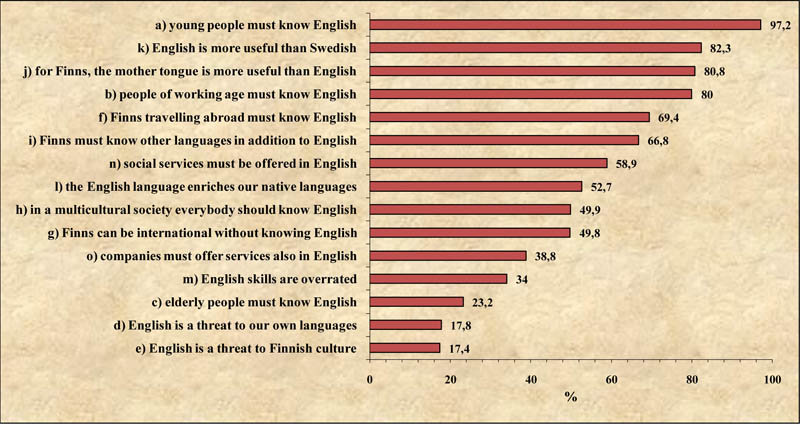

The statements in question 19 concerned the importance of English in Finland and internationally. The respondents were asked to respond to the following 15 statements on a five-point scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, or no opinion):

(a) young people must know English,

(b) people of working age must know English,

(c) elderly people must know English,

(d) the spread of English in Finland is a threat to our own languages,

(e) the spread of English in Finland is a threat to Finnish culture,

(f) Finns traveling abroad must know English,

(g) Finns can be international without knowing English,

(h) it is important for the development of a multicultural society that everybody should be able to speak English,

(i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English,

(j) for Finns, the mother tongue is more useful than English,

(k) English is more useful to Finns than Swedish,

(l) the English language enriches our native languages,

(m) English skills are overrated,

(n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish,

(o) all companies in Finland must offer services also in English.

To simplify the reporting of the results, we shall here refer to the percentages of those respondents who agree (strongly agree or agree) with the statements. This simplification does not lose any essential information. The proportion of respondents answering no

opinion was moderately low in the statements in question 19; it was only in statement (l) the English language enriches our native languages that the proportion was above one tenth (14 %) of the respondents.

Examination of the data (see Figure 27) produced the following findings: the vast majority of the respondents felt that both (a) young people (97 % agreed) and (b) people of working age (80 % agreed) must know English, but that (c) the elderly do not have to (only 23 % agreed with the statement offered). The majority of the respondents felt that (f) Finns travelling abroad must know English (69 %) and that (i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English (67 %). The majority of the respondents did not think that (m) English skills are overrated (though 34 % had the opposite opinion). Most Finns thus seem to have a neutral and practical attitude towards English. They feel that young people and adults, excluding the elderly, should know English.

Opinions on statements (h) It is important for the development of a multicultural society that everybody should be able to speak English and (g) Finns can be international without knowing English were divided more evenly. For these statements, the rates for agreeing and disagreeing were relatively close to each other.

FIGURE 27 The percentages of respondents who agree with the statements about the importance of English in Finland

Less than one fifth of the respondents saw the spread of English as a threat, either to (d) domestic languages (18 %) or to (e)

Finnish culture (17 %). Slightly more than half of the respondents indicated that (l) the English language enriches our native languages

(53 %). However, a clearer majority took the view that (j) for Finns, the mother tongue is more useful than English (81 %) and that

(k) English is more useful to Finns than Swedish (82 %). The majority (59 %) of the respondents felt that (n) social services

(e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish, but only 39 % took the view that (o) companies must offer services also in English.

From the above, it would appear that most respondents do not think that English could potentially displace Finnish and Swedish, or undermine Finnish culture. Interestingly, more than half of the respondents felt that English enriched the Finnish language and influenced it in a positive way. It appears that Finns place high value on their national languages and culture, even to the extent that these could benefit from the influence of English.

Between the sexes, only a few statistically significant differences were found (Table 19.1). Women agreed more often than men with the following:

(b) people of working age must know English,

(n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish,

(o) all companies in Finland must offer services also in English.

Men felt more often than women that:

(j) for Finns, the mother tongue is more useful than English,

(l) the English language enriches our native languages.

Comparisons by age group showed statistically significant differences concerning almost all the statements (Table 19.2). For many of the statements, the difference can be expressed simply as a difference between the two youngest (15–24 and 25–44) and the two oldest (45–64 and 65–79) age groups. The clearest difference concerned statement (m) English skills are overrated. Here 48 % of the 45–79 age group were in agreement, as opposed to 21 % of the 15–44 age group. Statement (f) Finns travelling abroad must know English was agreed to by 80 % of the respondents under the age of 45, but by only 60 % of respondents aged 45 and over. The statements with which the older age groups agreed more frequently than the younger were:

(d) the spread of English in Finland is a threat to our own languages,

(e) the spread of English in Finland is a threat to Finnish culture,

(i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English,

(j) for Finns, the mother tongue is more useful than English,

(m) English skills are overrated.

The statements with which the youngest age groups agreed more frequently than older age groups were:

(b) people of working age must know English,

(c) elderly people must know English,

(f) Finns travelling abroad must know English,

(h) it is important for the development of a multicultural society that everybody should be able to speak English,

(n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish.

In addition, the 25–44 age group differed from the other age groups in some statements. These included:

(a) young people must know English,

(l) the English language enriches our native languages.

Here, the proportion of respondents in agreement was higher in the 25–44 age group than in the other age groups. In addition, this age group

disagreed more often than other age groups with (g) Finns can be international without knowing English.

There is a clear difference in the attitudes of younger and older respondents: the older age groups take a more negative attitude towards English than the younger ones. They do not consider it to be as useful or as positive a phenomenon as younger people do. The younger respondents tended much more towards the opinion that everyone, regardless of age, should know English, and that society should function in English as well as in the domestic languages. An interesting finding is that the 25–44 age group – i.e. those persons who are most likely to have children and young people in their family, and who are likely to be interested in their future – are most clearly of the opinion that young people should know English.

Comparisons by area of residence revealed statistically significant differences concerning seven of the statements (Table 19.3). In general terms, city dwellers differed from the others. Other areas of residence did not differ from each other significantly. Residents of cities agreed with the following statements more often than the residents of other areas:

(b) people of working age must know English,

(f) Finns travelling abroad must know English,

(h) it is important for the development of a multicultural society that everybody should be able to speak English,

(i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English,

(n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish.

The situation was the opposite concerning (m) English skills are overrated. Country dwellers agreed with this statement more frequently than city dwellers.

A finding that differs from all the others comes from statement (o) all companies in Finland must offer services also in English. The respondents expressing strongest agreement were from the cities, and also from the countryside.

Overall, the answers reflect a difference between cities and the rest of Finland. More frequently than the others, residents of cities find it important that people of working age in particular should know English and other foreign languages, and that society as a whole should operate in English as well as in the domestic languages. Respondents living in the countryside were more likely than the others to feel that the English language is overrated in Finland.

In comparisons by level of education (Table 19.4), the least educated were again clearly distinct from the others. Compared to the other groups, they disagreed more frequently with the following statements:

(a) young people must know English,

(b) people of working age must know English,

(c) the elderly must know English,

(f) Finns travelling abroad must know English,

(h) it is important for the development of a multicultural society that everybody should be able to speak English,

(i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English,

(n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish.

However, the least educated respondents felt more often than others that (m) English skills are overrated. Highly educated respondents, for their part, were more likely than the others to agree with these statements:

(i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English,

(n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish.

In the same way as age, the level of education divides Finns into two groups in relation to English. The more educated the respondents were, the more positive was their attitude towards English and other foreign languages, and the more emphasis they placed on English as an important “civic skill”.

Differences between occupations varied greatly from statement to statement (Table 19.5). Managers and experts in particular, but also office and customer service workers, were more positive than healthcare workers and manual workers towards the following statements:

(b) people of working age must know English,

(c) elderly people must know English,

(i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English.

Manual workers felt less often than other occupations that:

(b) people of working age must know English,

(n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish.

In other respects, manual workers did not differ greatly from other occupations. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, managers felt more often than other occupations that (m) English skills are overrated. Moreover, they thought less often than others that (f) Finns travelling abroad must know English.

Office and customer service workers differed from other groups by a more negative attitude towards statement (j) for Finns, the mother tongue is more useful than English. Regarding statement (l) the English language enriches our native languages the majority of managers, office workers and manual workers were in agreement, but only a minority of experts and healthcare workers agreed. Regarding statement (n) social services (e.g. healthcare services) must be offered in English as well as in Finnish and Swedish, experts, office and customer service workers, and healthcare workers indicated most agreement, and manual workers and managers the least. Concerning the other statements, no striking differences were found.

In terms of occupation, the respondents’ language attitudes do not form clear classes. Respondents in managerial positions have interesting views: on the one hand they emphasise the usefulness and importance of English to Finns, but on the other hand they also find it overrated. For this group, it may be that skills in other languages seem just as important, an attitude which may be reflected in their agreement with statement (i) Finns must know other languages in addition to English. A distinction can be observed in those occupations in which people are most likely to have to use English. In these categories it is thought that Finns should know English, and that social services should be offered also in English. English tends to be considered least useful in those occupations that do not require the use of English.

4.1.8 English as an international language

The statements in question 20 dealt with English as a language used in international communication. This question derives from the fact that English is often used in international situations as a lingua franca, making it possible for the participants to communicate when they do not have any other common language. The respondents were asked to indicate on a five-point scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, or no opinion) their attitude towards eight statements concerning English as an international language:

(a) English is displacing other languages in the world,

(b) English skills should become more common in the world,

(c) the set of values that comes with English is destroying other cultures,

(d) English is spreading the market economy and materialistic values,

(e) English is the language of advancement,

(f) English skills add to mutual understanding on a global level,

(g) to be up-to-date, people must be able to function in English,

(h) people with English skills are more tolerant than those who cannot speak English.

FIGURE 28 The percentages of respondents who agree with the statements about English as a global language

As in question 19, the results here group together percentages for respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing with the statements. These percentages are shown in Figure 28. The percentages for different background variables are shown in the Tables 20.1–20.5. No opinion responses were more frequent here than in question 19. This applied especially to statement (h), in which the no opinion response rate was 21 %. Statements (c), (d) and (e) also received no opinion from over 10 % of the respondents.

The following results were obtained. The majority of all the respondents agreed with the following statements:

(a) English is displacing other languages in the world,

(b) English skills should become more common in the world,

(f) English skills add to mutual understanding on a global level,

(g) to be up-to-date, people must be able to function in English.

Slightly less than half of the respondents agreed with the following statements:

(d) English is spreading the market economy and materialistic values,

(e) English is the language of advancement.

A minority of the respondents agreed with these statements:

(c) the set of values that comes with English is destroying other cultures,

(h) people with English skills are more tolerant than those who cannot speak English.

It appears that Finns mainly have a positive attitude towards English as an international language, and find it a useful tool, enhancing

international communication and mutual understanding. What we find particularly interesting here is that when asked about English being a threat

to languages other than Finland’s national languages, the majority viewed it as a threat. The proportion is significantly larger than for statement (d) the spread of English in Finland is a threat to our own languages in question 19, where only 18 % were in agreement. It seems that Finns do not consider Finland’s national languages to be as vulnerable as other languages (spoken by small populations).

Between the sexes, a significant difference was found concerning these statements:

(b) English skills should become more common in the world,

(d) English is spreading the market economy and materialistic values.

More men than women agreed with both statements (see Table 20.1). Other statements were viewed similarly by men and women.

Between age groups (Table 20.2), statistically significant differences were found concerning all statements except for (h) people with English skills are more tolerant than those who cannot speak English. For this statement there were no significant differences between any subgroups. In many cases the differences between age groups can again be simplified into a contrast between the two youngest age groups (15–24 and 25–44) and the two oldest (45–64 and 65–79). The youngest age groups agreed more frequently with the following statements:

(b) English skills should become more common in the world,

(f) English skills add to mutual understanding on a global level,

(g) to be up-to-date, people must be able to function in English.

Concerning the following statements, the result was the opposite – older respondents more frequently agreed with the following statements:

(c) the set of values that comes with English is destroying other cultures,

(d) English is spreading the market economy and materialistic values.

Whereas young respondents view English positively and find it necessary in international contexts, older respondents are clearly more critical, seeing negative political influences connected with the spread of English.

Nevertheless, the contrast between younger and older respondents did not apply to statement (e) English is the language of advancement. Here, a narrow majority of both the youngest and the oldest age group agreed with the statement. In the mid-range age groups (25–44 and 45–64), the respondents who were in agreement formed a narrow minority. Concerning statement (a) English is displacing other languages in the world, the 25–44 age group differed significantly from the other age groups: 54 % agreed, whereas among the other age groups the proportion was over 60 %.

Between areas of residence (Table 20.3) significant differences were found regarding these statements:

(f) English skills add to mutual understanding on a global level,

(g) to be up-to-date, people must be able to function in English.

In simple terms, these were both cases of an opposition between cities and the rest of the country: agreement with these statements was more common in cities and in towns. It should be noted that statements (f) and (g) were also among the statements that the younger age groups viewed more positively than older age groups.

Comparisons by level of education showed statistically significant differences concerning five statements (Table 20.4). The two groups with the lowest level of education agreed most often with these statements:

(d) English is spreading the market economy and materialistic values,

(e) English is the language of advancement.

Agreement with the following statements increased with the level of education:

(f) English skills add to mutual understanding on a global level,

(g) to be up-to-date, people must be able to function in English.

The most essential finding concerning statement (a) English is displacing other languages in the world, was that those with a university degree agreed with it significantly more often than the others.

As in the answers to question 19, comparisons by level of education showed that respondents with the highest levels of education found English a useful language, enhancing mutual intelligibility; however, they were also worried about its influence on other languages. In most of the cases education does not seem to offer a clear explanation for the distribution of the responses – the answers might even reflect or be coloured by the respondents’ political views.

In comparisons by occupation, managers and experts differed in their opinions from healthcare workers and manual workers with regard to most

statements (Table 20.5). In general they showed more agreement with the statements. Office and customer service workers to some extent formed a group in the middle: depending on the statement, they had similar opinions to either managers and experts or to healthcare workers and manual workers. With regard to the following two statements, managers and experts showed more agreement than the other occupations:

(a) English is displacing other languages in the world,

(c) the set of values that comes with English is destroying other cultures.

Compared to other occupations, managers and experts seemed to be more critical regarding the influence of English on other cultures and languages.

The following statements received most agreement from managers and experts, and also from office and customer service workers:

(b) English skills should become more common in the world,

(f) English skills add to mutual understanding on a global level,

(g) to be up-to-date, people must be able to function in English.

Quite contrary to expectation, a positive attitude towards statement (e) English is the language of advancement, was most frequent

among office and customer service workers and healthcare workers. It was least frequent among experts.

4.2 Summary and discussion

Personal importance of English

More than half of the respondents viewed English as at least moderately important. The estimation of the importance of English was dependent on age, the geographical environment, and social status. The younger or more urban the respondents were, the more important English was to them: among the youngest age group 80 % and among city dwellers 73 % of respondents viewed it as important to themselves, personally. Occupation also affected the attitude to English: managers, experts, and office workers differed from other occupations. As was mentioned earlier, English is a part of young people’s lives through school, free time activities, and friends. In contrast, the importance of English in the older respondents’ lives is mostly explained by occupation and work tasks.

English in the respondents’ own environment

English is seen or heard in the respondents’ environment a great deal. The locations where English is encountered are directly linked to the kind of environment that respondents live in and move about in. In addition, age, education, and occupation correlate with the extent to which the respondents appear to see or hear English. English is encountered most frequently in streets, shops, stores, and restaurants – this was particularly typical for women’s responses. Almost 80 % of respondents in working life encountered English at work, and 71 % of students encountered it in their place of study. Encounters with English are especially linked to commercial contexts (see also Cenoz & Gorter 2009). English is not often seen or heard in institutional settings, offices, libraries, churches, or hospitals. In other words, the “official” linguistic landscape of Finnish society exists in the domestic languages only. For immigrants, for example, this may be challenging.

The attractiveness of English varieties

The response rate for question 15, in which respondents were asked to evaluate the appeal of varieties of English, was smaller than for the other questions in this section. Among elderly respondents and those with primary education only, the response rate was less than 70 %. These respondents probably did not recognise the varieties mentioned in the question, or were not able to evaluate their attractiveness.

British English and American English were found to be the most appealing varieties. American English was preferred by men, and in addition by young respondents, country dwellers, and manual workers. British English was preferred by women, city dwellers, and respondents with a higher level education. The popularity of British English is not surprising since British English has traditionally been the variety taught in Finnish schools. The popularity of American English is probably due to its spread, familiarity, and associations with popular culture, especially through music, TV series, and films.

The least appealing varieties were Indian English and Finnish English. Young respondents in particular look down on the Finnish way of using and pronouncing English. The oldest respondents reject American English most strongly, perhaps reflecting a more general antipathy towards the United States and the values associated with that country. All in all, the answers reveal that “authentic” varieties spoken by native speakers appeal to Finns. Non-native varieties of English are viewed as problematic, including Finns’ own way of using English. Finns associate good language skills with the notion of a non-native speaker who is able to sound like a native-speaker, and who does not show his/her own national origin in speech. In this sense Finns do not see English as “belonging to them”. They still treat it essentially as a foreign language, one used with an adopted “foreign” identity. In this respect Finns differ from many speakers of established World Englishes, for whom English has become one of their own languages, and for whom their own way of using the language and their own accent is acceptable in terms of displaying their ethnic and national identity (see e.g. Meshtrie & Bhatt 2008).

Teaching conducted in English

Almost all the respondents (approaching 90 %) viewed teaching in English positively. Age group comparisons showed that the most positive attitudes were found in the two mid-range age groups, perhaps because schoolchildren’s parents are likely to belong to those groups. In other words, the issue is of more immediate relevance to them than to young or retired respondents.

In the cities, attitudes towards English language instruction were somewhat more positive than in the countryside. The difference may reflect the fact that English language instruction is offered mainly in urban and semi-urban municipalities (see Lehti et al. 2006).

Finns’ fairly positive attitude towards Finnish children’s attendance at English-speaking schools can be seen as surprising, considering the public debate that has been going on around the subject (see Virtala 2002; Härkönen 2005; Leppänen & Pahta, forthcoming). In this debate it is often suggested that English language instruction may threaten skills in the mother tongue and in other school subjects (Hakulinen et al. 2009).

English as the language of Finnish companies

Respondents were more often for than against the use of English as the internal language of companies: over 60 % viewed the phenomenon positively. In particular, young respondents of working age and city residents had positive attitudes towards this use of English, whereas older respondents and country dwellers had twofold opinions. Many of the retired respondents could not form an opinion at all.

The distribution of answers reflects the fact that even though English has been part of Finnish working life for a fairly short period of time, the recent internationalisation and globalisation of working life has made Finns more aware of the increasing need for English in many expert positions. The answers also indicate that respondents of working age in particular think that future employees should know English, even if they do not see English skills as necessary in their own situation.

Attitudes to English spoken by Finns

When a Finn speaks English, he or she should basically sound like a native speaker: 54 % of the respondents admire, and 23 % feel pride in Finns when they hear a Finn speaking English like a native speaker. If a Finn speaks with a Finnish accent, but fluently, he or she is still admired (28 %), with 24 % of the respondents feeling pride in Finns. If a Finn speaks English poorly, the respondents feel sympathy, amusement, and irritation. Negative feelings towards a Finn speaking English poorly are more common among young people and slightly more common among men than women. Elderly respondents seem to value a good effort, whereas younger respondents clearly have higher standards. Older country dwellers with a low level of education do not appear to place as much value on native-sounding speech as do those who are young, well-educated, and living in cities.

The importance of English in Finland

Finns consider foreign language skills to be extremely important: the view is that young people (97 %) and people of working age (80 %) should know English, but that for the elderly (23 %) it is not as necessary. When travelling abroad, English skills are seen as necessary (69 %), but it is thought that people should know other languages in addition (67 %). These results demonstrate how Finns genuinely appreciate English and want to learn it, but the same thing applies to other languages as well. Finns are interested in and motivated to study foreign languages, and in this respect differ from many other Europeans – particularly speakers of languages spoken by large numbers of people – who are not nearly as interested in foreign language studies (cf. Eurobarometer 2006). Keeping in mind the Finns’ interest in foreign languages, one may be alarmed at how far the language choices in schools are becoming narrowed down (Saarinen 2008; Puustinen 2008). The mother tongue is still considered more useful than English (81 %), but English is seen as more useful than Swedish (82 %). In this atmosphere, especially when English is spreading through unofficial cultural channels as well, it may be difficult to strengthen the status of Swedish or even – despite legislative measures – to maintain it as a language studied by the Finnish-speaking population.

English is not viewed as a threat to domestic languages and culture (83 %). Hence, the majority of Finns have fairly neutral and practical attitudes towards English. In this respect the majority of Finns seem to disagree with the prominent voices in public debate, expressing fears that English will fragment and displace Finnish national languages and culture. Interestingly, over half of the respondents viewed the influence of English on the Finnish language as positive and enriching.

Almost all the young respondents felt that young people should know English, thus underlining the fairly central role that English already has in young people’s lives. In the youngest age group the respondents felt that every Finn should know English, and that Finnish society itself should function in English as well as in the domestic languages. Older age groups do not consider English to be as necessary or as positive as younger people do. The answers also revealed a dichotomy between the positively-disposed urban population and the negatively-disposed rural population – and a similar difference between highly-educated and less educated respondents. On the other hand, comparisons by occupation did not reveal such clear divisions.

From these results, it appears that Finland is divided in two from the point of view of the respondents’ views and attitudes: English emerges as “linguistic capital” for the young and those leading an urban lifestyle, whereas older people, less educated people, and country dwellers have a more distant, negative, and less personal relation to English.

Status of English as an international language

In general, English was seen as important for internationality: 90 % of the respondents felt that skills in English enhance mutual understanding on a global scale, 74 % felt that to be up-to-date one must know English, and 60 % felt that English skills should become more common. English is associated with trendsetting, and is basically seen as something that modern people should be proficient in. Here again we notice that Finns have fairly pragmatic attitudes towards English, that is, they take the view that English is necessary for international communication. Nevertheless, the majority (60 %) of the respondents took the view that English was displacing other languages, though only 30 % believed that it was having a destructive effect on other cultures. Here an interesting contradiction was found between attitudes towards the influence of English on Finland’s own national languages and culture, as compared to the effect on other languages and cultures. English was seen as a threat to other languages, but not to Finland’s national languages. Finns would thus appear to have a high degree of confidence in their own languages, and in their continuing status and vitality.

The results again show differences between the young and the old: young respondents emphasised the importance of English skills, while the old were more critical. In comparisons between occupations, managers and experts constantly differed from healthcare workers and manual workers by agreeing more frequently with almost every statement. In other words, managers and experts viewed English skills as important because of internationality, but their answers also revealed critical attitudes towards the “imperialistic” influence of English in the world. The comparisons by other background variables showed fewer differences, or else were not found to be consistent.

Back to top

|