5 STUDYING AND KNOWING ENGLISH

The aim of this section was to discover how Finns experience and evaluate their English skills. The questions in this section (21–25) concerned the respondents’ background in English studies, their self-evaluation of different aspects of their language skills, their experience of their own language skills (for example compared to the skills of other Finns), and the origins of their English skills.

Finns are generally seen as having good language skills, and languages have traditionally been a major part of the school curriculum

(Pöyhönen 2009). However, encounters with English and learning experiences in English are no longer restricted to formal learning environments (Leppänen et al. 2008; Nikula & Pitkänen-Huhta 2008; Piirainen-Marsh & Tainio 2009a, 2009b). Increasingly, Finns are encountering and learning English as part of their daily activities. Language skills are likely to have a connection to language use, and possibly also to attitudes towards the language in question. Thus, we see it as important to study the respondents’ own notions of their skills. It should be noted here that our investigations cover those who do not know English as well as those who do (cf. Preisler 1999; Pitkänen-Huhta & Hujo, forthcoming).

5.1 Results

5.1.1 Duration of English studies

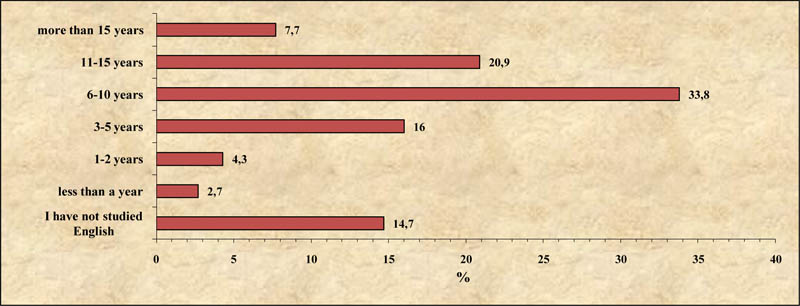

Question 21 asked respondents how long they had studied English in total. By “English studies” we meant both studies with an instructor and self-studies. Seven options were given, from I have not studied English at all to more than 15 years

(see Figure 29 and Tables 21.1–21.5). The most frequent response was

6–10 years, which was chosen by over one third of the respondents. Approximately 15 % of the respondents had not studied English at all.

FIGURE 29 The distribution of the duration of English studies

Men and women differed in that 18 % of men and only 11 % of women had not studied English at all. In addition, the proportion of respondents who had studied English for 6–10 or 11–15 years was higher among women than men (60 % of women and 50 % of men) (Table 21.1).

Comparisons by age group (Table 21.1) demonstrated how English has become the most important foreign language taught in Finnish schools. In the oldest age group (65–79) more than half had not studied English at all. Similarly, a high proportion (23 %) of persons aged 45–64 had not studied English. Those aged 45–79 who had studied English had mostly studied it for 3–10 years. In the youngest age groups (15–24 and 25–44) English was typically studied for 6–15 years. Few in this age group had studied English for less than two years or not at all. Among those who had studied English for a long period (at least 11 years) a clear difference was found between the two youngest and the two oldest age groups: among those aged 25–44 around half of the respondents had studied English for at least 11 years, whereas among the 45–64 age group the response fell to 13 %, and among the 65–79 age group to less than 6 %. This clearly reflects the Finnish reform in basic education that began in the 1960s; it was then that English studies were initiated at primary school level.

Comparisons by area of residence (Table 21.3) showed that the extent of

English studies increases consistently from the countryside to rural centres and cities. For example, in the countryside, 23 % of the respondents had not studied English at all, whereas the proportion was 10 % in cities. Respondents who had studied English for a long period (at least 11 years), were found mostly in cities (39 %). In other areas, 14–25 % of the respondents had studied English for at least 11 years. The proportion was smallest in the countryside.

Comparisons by level of education (Table 21.4) revealed a direct relationship between the level of education and studies in English: the higher the level of education, the more extensive were the English studies. Of those who had attended only primary education, as many as 70 % had not studied English at all, and none of this group had studied English for more than 10 years. Among respondents with a university education, all had studied English, the majority (87 %) for at least 6 years. Most frequently the duration of English studies among those with a polytechnic or university education was 11–15 years (for both approximately 35 %). The proportion of those who had studied English for over 15 years was higher among university graduates (23 %) than polytechnic graduates (17 %). Among those with education at upper secondary school, vocational school, or lower secondary school, the most common option was 6–10 years (40–42 %). Hence, English is studied at all levels from primary school to university (cf. question 10).

Compared to other occupations (Table 21.5), manual workers included a

considerably higher proportion (32 %) of persons who had not studied English at all. Furthermore, this group included the smallest proportion (15 %) of respondents who had studied English for a long period (at least 11 years). The highest proportion of respondents who had studied English for 11 years or more was found among experts (44 %). In this group the proportion of respondents saying I have not studied English at all was clearly smaller than among other occupations. Managers came second in the length of English studies. These findings are clearly linked to the high levels of education associated with the above occupations.

5.1.2 Self-evaluation of English skills

Question 22 asked respondents to evaluate their English in the areas of (a) speaking skills, (b) writing skills, (c) reading

skills, and (d) comprehension of spoken English on a six-point scale (fluently, fairly fluently, moderately, with difficulty, only a few words, not at all). Note that self-evaluation was the only way to map the various language skills, since other evaluations could not have been obtained from such a heterogeneous group of respondents. Self-evaluations are frequently used in large-scale studies on language skills

(Eurobarometer 2001, 2006; Hilton et al. 1985). In most cases self-evaluation has been found to be a reliable way to evaluate the level of language skills (Blanche & Merino 1989; Oscarson 1997; Ross 1998). Problems occur mainly with very young respondents, or when experience in language use is minor, or when language skills are very weak.

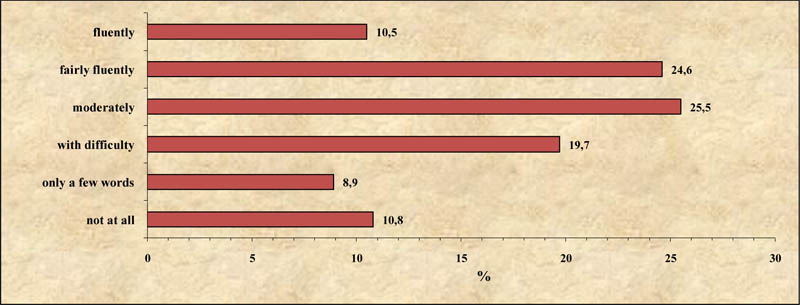

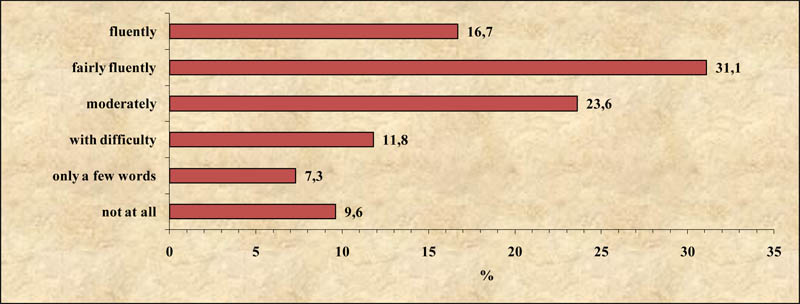

The distribution for speaking skills is presented in Figure 30. Most responses were covered by the options fairly fluently and

moderately (these options together made up 50 % of the respondents). However, 11 % indicated that they did not speak English at all,

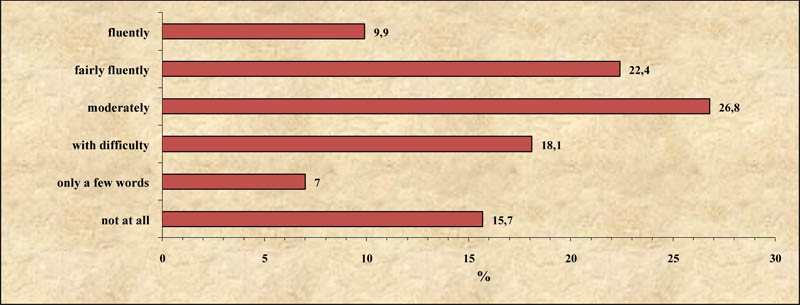

corresponding fairly well (though not exactly) to the percentage of respondents who had not studied English (15 %). The distribution for writing

skills in English (Figure 31) was similar, but the percentage for not at all was higher (16 %). The rates for fluently and

fairly fluently were slightly lower (the figure fell from 35 % to 32 %).

FIGURE 30 The distribution of the respondents’ proficiency in speaking English

FIGURE 31 The distribution of the respondents’ proficiency in writing English

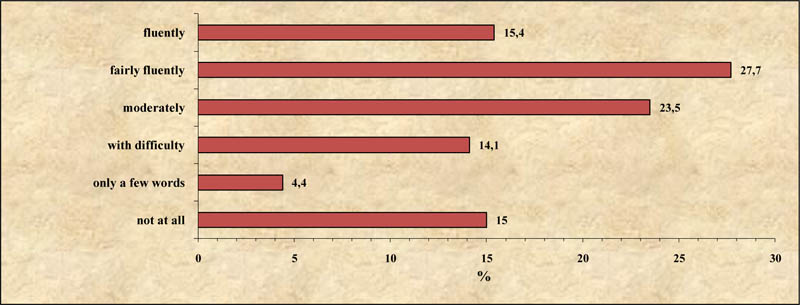

From the distribution for reading skills in English (Figure 32), one can see that reading is often found to be easier than speaking or

writing (the proportions for fluently and fairly fluently were higher than for speaking and writing; the two options made up 43 %

of the respondents). However, 15 % of the respondents indicated that they could not read English at all.

Skills in understanding spoken English were generally rated as somewhat higher (Figure 33). The proportions for fluently and fairly fluently were the highest among the four English skills investigated (together totalling 48 %), and the proportion for not at all was the lowest. It should be noted that even though 15 % of the respondents indicated that they had not studied any English, less than 10 % said they did not understand spoken English at all. This would suggest that Finns have probably learnt a great deal of English via music, TV and films, even if they do not consider this to be self-study.

FIGURE 32 The distribution of the respondents’ proficiency in reading English

FIGURE 33 The distribution of the respondents’ understanding of spoken English

Overall, the respondents’ highest self-evaluation was for understanding spoken English and the second-highest was for reading.

The active production of English in speech, and particularly in writing, was perceived as weaker.

Differences between the sexes were shown first and foremost in the options only a few words and not at all. Here, the proportions were higher for men in all the skills covered (Tables 22a.1–22d.1). However, in speaking skills the difference was minor compared to the other skills (not statistically significant).

The age groups differed from one another very clearly, regardless of the skill (Tables 22a.2–22d.2). Compared to the older groups, young respondents gave considerably higher ratings to all their English skills. The division seemed to come between the two younger age groups (15–24 and 25–44) and the two older age groups (45–64 and 65–79), and it applied most clearly to the extreme options, i.e. fluently and fairly fluently as opposed to only a few words and not at all. Thus, among the oldest age group, 55–62 % (depending on the skill) chose the options only a few words or not at all, and only 7–10 % the options fluently or fairly fluently. By contrast, among the youngest age group, the proportions were as low as 1–3 % for only a few words or not at all, and as high as 54–72 % for fluently or fairly fluently.

Comparisons by area of residence (Tables 22a.3–22d.3) again revealed an

obvious and statistically highly significant difference between urban and rural areas. The difference was basically the same for all four skills. The respondents mastering English fluently or fairly fluently most frequently live in cities, and least frequently in the countryside. Conversely, the option not at all was chosen by a clearly higher proportion of country dwellers than city dwellers.

Comparisons by level of education and occupation produced the same predictable results, which again were similar for all the English skills. The higher the respondents’ level of education, the more highly they rated their English skills (Tables 22a.4–22d.4). Managers and experts rated their English skills at least with the option moderately: depending on the skill, 52–66 % of managers and 47–63 % of experts answered this way. The proportion was slightly lower among office and customer service workers, which is mainly due to the fact that they more rarely rated their skills as fluent, and chose the option not at all more often than managers or experts. The proportion of respondents choosing the option not at all was even higher among healthcare workers and especially manual workers. The option fluently was indicated only rarely in these groups (Tables 22a.5–22d.5).

5.1.3 Ratings of respondents’ own English skills

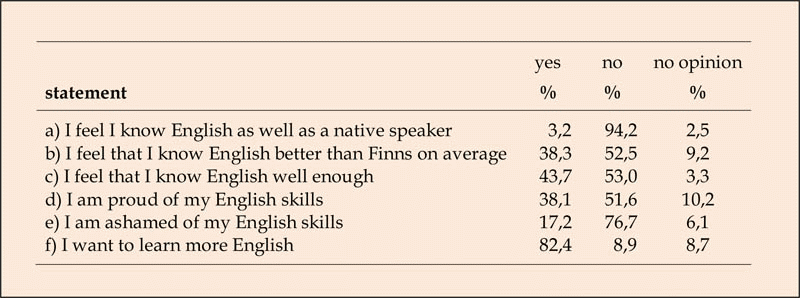

Question 23 asked respondents to rate their own English skills. Here, we wanted to deepen the previous self-evaluations, going beyond the scale-ratings used in Question 22. We also wanted to know not just about the respondents’ own skills, but also about how they saw themselves in comparison with others. The instructions made it clear that only those who in question 22 had indicated at least a slight knowledge of English (approximately 90 %) should answer. The question included the six statements (a)–(f) presented in Table 11. To each statement the respondents were to answer either yes, no, or no opinion.

TABLE 11 The distribution for the statements (a)–(f) in question 23

Table 11 shows that only a small proportion of the respondents felt that they knew English as well as native speakers. As regards the other

statements, the respondents answering yes were in the minority, except for statement (f), according to which over 80 % of the respondents wanted to learn more English. However, in statement (c) 40 % of the respondents felt that they knew English “well enough”. In statement (b) the respondents were fairly modest concerning their English skills: only 38 % felt that they knew English better than Finns on average.

Men and women differed with regard to statements (b) and (e). Men were more likely than women to feel that they knew English better than Finns on average, and were less likely to be ashamed of their English skills than women (Tables 23a.1–23f.1).

The age group differences were found to be statistically significant for all the statements (Tables 23a.2–23f.2). In the case of statement (e) the proportion of respondents answering yes increased with age. In other words, the older respondents indicated that they were ashamed of their English more frequently than the younger ones. With the other, more positive, statements the opposite trend was found: the young respondents were more likely to see their English skills as good than the older ones, to be proud of their skills, and to wish to learn more. With statements (b) and (f) the trend was different from the others, in the sense that no difference was found between age groups 15–24 and 25–44. The proportion of respondents answering yes started to decrease with age only among the older age groups.

Comparisons by area of residence showed a clear opposition between cities and other areas (Tables 23a.3–23f.3). In these questions the countryside did not differ significantly from the towns. In the cities the proportion of those who viewed their English skills as good (statements (a)–(c)), who were proud of their skills (d), and who wanted to learn more (f) was substantially higher than in other areas of residence. Town dwellers and country dwellers indicated more often than city dwellers that they were ashamed of their English skills (e).

The respondents’ level of education correlated with the answers as directly as one would expect: the respondents with the highest level of

education were the ones who were most likely to feel that they knew English well and wanted to learn more, and the least likely to feel ashamed of their skills (Tables 23a.4–23f.4).

Comparisons by occupation also gave consistent results (Tables 23a.5–23f.5). According to statements (a)–(e), the most positive views of their own English skills were held by managers and experts. At the other extreme were healthcare workers, who (for example) were ashamed of their English skills more often than others. In the case of statement (f) the differences between occupations were somewhat contradictory. This statement obtained the highest proportion of positive responses from experts and from office and customer service workers. The largest proportion of negative responses came from manual workers. Healthcare workers and managers formed a middle group.

5.1.4 Feelings of inadequacy in English skills

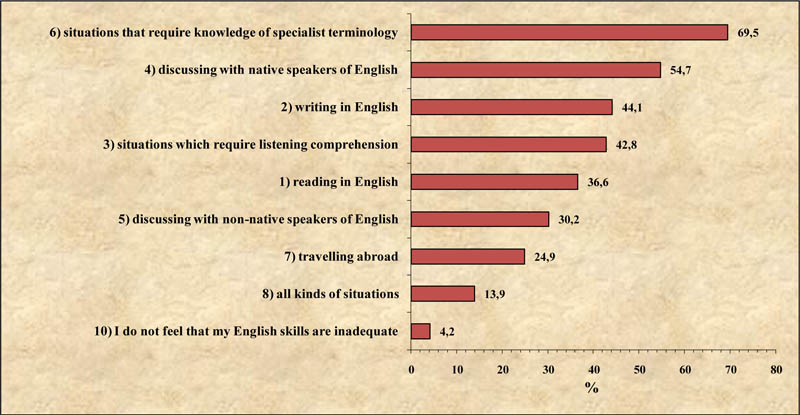

With question 24 we wanted to discover the kinds of situations in which Finns feel their English skills are inadequate. Here

we also sought to deepen our understanding of the respondents’ language skills. According to the instructions, the question was only to be answered by those respondents who in question 22 had indicated that they knew English at least a little (approximately 90 % of the respondents). The question listed nine situations in which a sense of inadequacy might be felt:

(1) when reading in English,

(2) when writing in English,

(3) in situations which require listening comprehension (e.g. on the telephone),

(4) when discussing with native speakers of English,

(5) when discussing with non-native speakers of English,

(6) in situations that require knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon,

(7) when travelling abroad,

(8) in all kinds of situations,

(9) elsewhere, where?

As a tenth option we listed statement (10) I do not feel that my English skills are inadequate in any situation.

The respondents were allowed to choose as many of the options as they wished. Possible inconsistencies were solved via the interpretation

that if any of options 1–9 were chosen, this ruled out option (10) I do not feel that my English skills are inadequate in any situation. It was assumed that when option (8) in all kinds of situations was chosen it included all given options even if they had not been ticked. Alternative (9) elsewhere, where? obtained only a few explanations. In each case it was possible to reassign the explanation to another possible option, hence this response was excluded from the analysis as a category on its own.

The response distribution is presented in Figure 34. It shows that only 4 % of the respondents did not find their English skills inadequate in any situation. The most frequent inadequacy indicated was (6) in situations that require knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon. More than half of the respondents who answered the question indicated (4) when discussing with native speakers of English, but only one third felt that their skills were inadequate when discussing with a non-native speaker of English. However, when drawing conclusions it should be noted that the respondents were only asked to choose the situations in which they felt inadequacy. Moreover, the fact that a situation was not chosen does not necessarily mean that the respondent might not potentially feel inadequacy. After all, it might simply be that the situation (e.g. requiring knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon) is not one that the respondent regularly encounters. This may to some extent complicate comparisons, making it difficult to draw detailed conclusions from the percentages for different background variables (Tables 24.1–24.5).

FIGURE 34 The percentages of the respondents who think that their proficiency in English is inadequate in different types of situations

The distributions for men and women (Table 24.1) did not significantly differ from one another except in the case of option (6) in situations that require knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon. Here, women felt inadequacy more frequently than men.

In almost all the situations, the age groups showed statistically significant differences (Table 24.2). We had assumed that older people would feel their language skills to be inadequate more often than younger people. This was indeed the result in four situations:

(1) when reading in English,

(3) in situations which require listening comprehension (e.g. on the telephone),

(7) when travelling abroad,

(8) in all kinds of situations.

However, in alternative (6) in situations that require knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon the results were the opposite: here the inadequacy actually decreased in parallel with increasing age. We would suggest that this is not due to younger people’s skills being generally weaker than those of older respondents. It seems more likely that young people more frequently encounter situations where specialised language skills are demanded. A similar finding emerged from situation (4) when discussing with native speakers of English. This option was chosen more often by the 15–24 age group than by the 65–79 age group as a situation where skills were felt to be inadequate. Most of the respondents who did not feel their language skills to be inadequate were found in the 25–44 age group, whereas the age group 65–79 felt the most inadequate in their language skills.

This question also demonstrated the division between cities and other areas. This division applied to all the options (Table 24.3). Respondents living in other areas felt their English skills to be inadequate more often than those living in cities. Situations requiring knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon (6) formed an exception: this option was chosen less frequently by country dwellers than by city dwellers. Here we are probably dealing with the same phenomenon that was detected in comparisons by age group, namely that country dwellers are less likely to encounter situations requiring specialist terminology than residents of cities.

As regards the level of education (Table 24.4), the respondents with the lowest level of education felt inadequacy more often than others in most situations. Again, situations requiring knowledge of specialist terminology (6) formed an exception. This alternative was less often chosen by respondents with the lowest level of education – possibly because they do not often encounter such situations. All in all, the feeling of English skills being inadequate was rarest among those with a university education. The proportion of those not feeling their language skills inadequate was also highest in this group (10 %).

In comparisons between occupational groups, healthcare workers and manual workers were those who most frequently found their English skills

inadequate, whereas managers and experts were the least likely to feel inadequacy (Table 24.5). Concerning alternative (6) in situations that require knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon, office and customer service workers often felt their language skills to be inadequate. It is notable that as many as 17 % of the managers chose option (10) I do not feel that my English skills are inadequate in any situation.

5.1.5 Where English is learnt

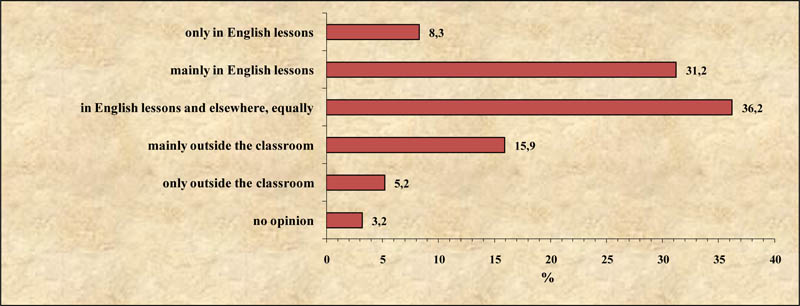

Question 25 asked respondents to indicate where they had acquired their English skills. As an introduction to the question it was stated that Finns learn English in both English lessons and everyday contexts, for example at work or in their leisure activities. (This statement is based on earlier qualitative studies, e.g. Nikula & Pitkänen-Huhta 2008; Luukka et al. 2008.) Six options were given and respondents were asked to choose only one of them. The options were: only in English lessons, mainly in English lessons, in English lessons and elsewhere equally, mainly outside the classroom, only outside the classroom, no opinion. The distribution is shown in Figure 35.

FIGURE 35 The place where the respondents’ proficiency in English has been learnt

The majority of the respondents indicated that they had learnt English mainly in English lessons or in English lessons and elsewhere equally. The subgroup differences were statistically significant for all the background variables included. Women learnt English in lessons more frequently than men, whereas men learnt outside the classroom more frequently than women (Table 25.1). The youngest age group (15–24) chose the option mainly in English lessons clearly more often than the other age groups (Table 25.2). Among the 25–44 age group, obtaining English skills from elsewhere in addition to lessons was more common than in the other age groups. The proportion of respondents who had learnt English only outside the classroom was highest in the two oldest age groups (45–64 and 65–79), ranging from 9 % to 16 %. In addition, the options only in English lessons and no opinion were more common in these age groups than in the younger ones. This polarisation may reflect first of all, the relatively few years of formal education undergone by older respondents. Secondly it may reflect the high proportion of those who have not used English since their school years.

Comparisons by area of residence show similarities to comparisons by age group, with a similar polarisation. The distribution of the country

dwellers is similar to that of the two oldest age groups: in the countryside there are most likely to be respondents who have not improved their English skills since school, and also those who did not study English at school. In addition, acquiring English skills outside as well as inside the classroom becomes more common as the focus shifts from the countryside to the larger population centres.

Respondents with a university education mostly felt they had learnt their English skills in English lessons and elsewhere equally;

the proportion (52 %) was significantly higher among this group than in the other groups (Table 25.4).

Comparisons by occupation (Table 25.5) revealed that healthcare workers were most likely to feel that they had learnt their English skills either only or mainly in lessons. The highest proportions of respondents who had learnt in English lessons and elsewhere equally were found among managers and experts, who also chose the option mainly outside the classroom more frequently than other occupations. Manual workers (tending to have lower levels of formal education) chose the option only outside the classroom more frequently than the others.

5.2 Summary and discussion

Duration of English studies

More than four out of five Finns have studied English. In other words, approximately 15 % have not studied English at all. The most common (34 %) duration for English studies is 6–10 years, which corresponds to basic and secondary education. Nearly one third have studied English for more than 10 years, which means they have probably attended further studies after basic and secondary education. Correlations with age, area of residence, level of education, and occupation are significant: young respondents, residents of cities, highly educated persons, managers, and experts have studied English the longest. In particular, the oldest respondents differed from the rest by their limited study of English. The effect of the Finnish education reform of the 1960s can clearly be seen, with respondents born in the 1960s having studied English for significantly longer than older respondents.

Skills in English

Approximately 18 % of the respondents indicated that they could not speak, write, read, or understand spoken English, and 9 % indicated that they had not mastered any of these four areas of language skills. It was found easiest to understand spoken English and second easiest to read English. Speaking and writing were considered more difficult by the respondents. In other words, passive receptive skills were found to be better than active productive skills. It may be that the opportunities for producing English are rarer than the opportunities for comprehending it. This is certainly true in terms of everyday activities (e.g. music, TV, websites). One may wonder also whether it reflects the emphases given to different skills in school teaching.

In all the skills, substantially more than 50 % and up to almost 70 % of the respondents rated themselves as having mastered English at

least moderately. Once again, a clear division was detected between the extremes. At one end were young people, city dwellers, highly educated

people, and people in managerial positions. At the other end were older respondents, country dwellers, people with less formal education, and

manual workers. This could be due to various factors: cities may offer more opportunities for using English, young people have, in a sense,

grown up with English use as part of their lives, and in complex international tasks the amount of English use may be significant. We may

therefore ask whether English skills are somehow connected with being well-off (cf. Kainulainen 2006) – and also whether English skills have become an absolute and unavoidable necessity for success in present-day Finland.

English skills and inadequacy

The vast (80 %) majority of the respondents wanted to learn more English, even though a high proportion (44 %) felt that they knew English

well enough already, and almost as high a proportion (38 %) were proud of their skills. In comparing their skills with other language users,

the respondents were rather modest: only a small minority (3 %) believed their skills to be on the same level as a native speaker of English,

and more than half (52 %) evaluated their skills as weaker than those of Finns on average (women more frequently than men). Thus, Finns neither

boast about their language skills nor are ashamed of them (only 17 % indicated that they were ashamed of their English skills). Even though

the young respondents took more pride in their skills than the older ones, they were also the ones who were most likely to want to advance further in English. This finding might suggest that young people are in effect aiming at fluent bilingualism, since despite rating their own skills quite highly in all areas of language (and much higher than the self-ratings of older respondents) they still wished to make progress as users of English.

Only 4 % of the respondents did not find their English skills inadequate in any situation, and these respondents were mainly young people,

living in cities, having a high level of education, and working in managerial positions or as experts. In contrast, 14 % of the respondents saw their English skills as inadequate in all situations. These were typically older respondents, with less formal education, living in rural areas, and doing manual work. Inadequacy was felt most in situations requiring knowledge of specialist terminology or jargon (70 %). In addition, inadequacy was indicated regarding conversation with native speakers of English (55 %) – which is interesting in view of the fact that the respondents also recorded their admiration of native speech (questions 15 and 18). This may relate to linguistic norms: language learners compare themselves to native speakers and strive for similar “good” language skills.

Overall, it appears that Finns rate their language skills as relatively good, but do not see their skills as adequate in concrete situations

of language use. Although they may have good skills in general terms, particular situations give rise to problems. It may be that this sense of

inadequacy fuels the desire of Finns to advance further in English.

Where English is learnt

Generally speaking we can say that one third of Finns feel they have learnt their English mainly in the classroom, and a further third both

inside and outside the classroom. Education plays a major role in language learning and Finns may still see English as a foreign language, one

that is mainly learnt though formal instruction. Particularly in the case of older respondents with fewer years of education and living in rural

areas, English would have been acquired in the school context, with little practice outside the classroom. Nevertheless, this group also includes the largest proportion of those who did not study English at school at all. Interestingly, it also includes the largest percentage of those who learned their English outside the classroom. Young, highly educated respondents living in cities and working as managers or experts also tended to have acquired their good English skills outside as well as inside the classroom – due presumably to the wider variety of opportunities for learning and using English.

Regarding studying and knowing English, we found that respondents were polarised into two groups: on the one hand there were the young,

highly educated respondents living in cities and working in managerial positions or as experts; on the other hand there were the older, less educated respondents living in rural areas and doing manual work. The first group had studied English longer, rated their skills more highly, felt less inadequacy concerning their skills, and had learnt their English both in and outside the classroom.

Back to top

|