3 LANGUAGES IN YOUR LIFE

The section Languages in Your Life (questions 4–12) aimed at forming an overall picture of the role played by languages in the respondents’ lives, and of how English fits within this picture. In Finland, foreign language skills have traditionally been valued highly, and the study of languages has been emphasised in schools (see e.g. Numminen & Piri 1998). However, the multilingualisation of Finnish society is not entirely due to education. Increased migration to and from Finland and the general internationalisation of the way of life have added to the number of languages used in Finland (see Latomaa & Nuolijärvi 2005). What we lack is research-based information on the extent to which encounters with different foreign languages are part of Finns’ everyday lives. In this chapter we shall look at foreign languages, including how they are used and studied, before moving to specific questions concerning English in later chapters. Here, we are mainly interested in the mother tongue of respondents and their family members, whether the respondents see themselves as mono-, bi- or multilingual, possible residence abroad, the range of foreign languages studied, encounters with different foreign languages in everyday surroundings, and the use of foreign languages in different contexts. The aim is to gain information on how language studies and changes in society may be affecting Finns’ linguistic repertoires.

3.1 Results

3.1.1 Respondents’ mother tongue

Question 4 asked respondents to indicate their mother tongue by choosing one of five options (Finnish, Swedish, Sámi, Estonian, or Russian), or by indicating some other language. The distributions are presented in Tables 4.1–4.5, The great majority of the respondents (93 %) had Finnish as their mother tongue. Second came Swedish (5 %) and third came Russian (1 %). Other languages (Thai, Polish, Turkish, Hungarian, Vietnamese) received only single responses. The distribution corresponds well to the language distribution of the Finnish population as a whole. However, none of the respondents gave Sámi as their mother tongue.

No statistically significant difference was found between the sexes. Nor were statistically significant differences found in respect of age group, area of residence, or occupation. Comparisons of educational level revealed that among Swedish-speakers, the largest proportion of respondents (8.5 %) fell within the highest educational category.

3.1.2 Mother tongue of family members

Question 5 asked if the respondents had family members with a mother tongue different from that of the respondent. Those responding positively were further asked what language the family member with a different mother tongue spoke (see Tables 5.1–5.5). The proportion of respondents for whom all family members had the same mother tongue was 92 %. This percentage was slightly smaller among men (90 %) than among women (94 %). As mother tongues different from that of the respondent, mention was made of English, Dutch, Japanese, Swedish, Sámi, German, Finnish, Swahili, Thai, and Russian.

In comparisons by age group it was found that the 25–44 age group showed a somewhat higher percentage in respect of family members with a different mother tongue. In comparisons by area of residence, a similar tendency was found among respondents living in large cities. Furthermore, having family members with a different mother tongue was more frequent among those with higher levels of education, though with something of a peak also among those with lower secondary education. A high frequency was also observed among managers. All in all, these results would suggest that the multilingualisation of Finnish families is a feature relevant to urban, young, and highly educated people. In contrast, the linguistic situation of the Finnish population as a whole can best be characterised as monolingualism.

3.1.3 Respondents’ mono- and multilingualism

Question 6 was in two parts. In 6a respondents were asked to indicate whether they saw themselves as mono-, bi-, or multilingual (Tables 6a.1–6a.5). Question 6b was relevant only to those who saw themselves as bi- or multilingual. In 6b, respondents were asked to choose from nine options the background factors that had, in their opinion, affected their bi- or multilingualism. The options were parents, relationship, living abroad, education, work, hobbies, friends, travel, and other factors, what?. The distributions for question 6b are shown in the Tables 6b.1–6b.5.

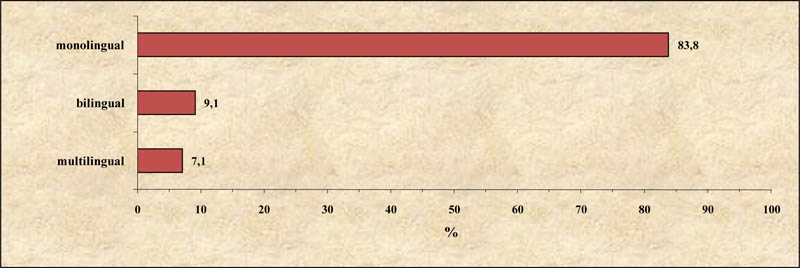

From the responses to 6a it appeared that the majority of the respondents (84 %) saw themselves as monolingual. Those who saw themselves as bilingual were somewhat more numerous than those who saw themselves as multilingual (Figure 3). In the light of this result, it would appear that Finns are not especially multilingual, and that they do not seem to regard their foreign language studies (cf. question 10) as a process of multilingualisation. This would suggest a traditional conception of bi- and multilingualism, according to which partial command of foreign language is not seen as bi- or multilingualism. Instead, bi- and multilingualism would be understood as involving wide-ranging, often native-like language skills.

There was no statistically significant difference between the sexes on whether the respondents saw themselves as mono-, bi-, or multilingual. In comparisons by age group we noticed that in the oldest age group 90 % of the respondents saw themselves as monolingual, with the percentage

decreasing steadily towards the younger age groups. Consequently, most bi- and multilingual respondents were found in the youngest age group (14 % and 10 % of the respondents). In comparisons by area of residence, the number of monolinguals increased and the number of bi- and monolinguals decreased systematically as the focus shifted from large cities to the countryside. In relation to level of education, most monolinguals were found among respondents with a low level of education. Between occupations there were no great differences; there were slightly more monolinguals among healthcare workers and manual workers than in other occupations.

FIGURE 3 The distribution for the question “Do you consider yourself to be mono-, bi-, or multilingual?”

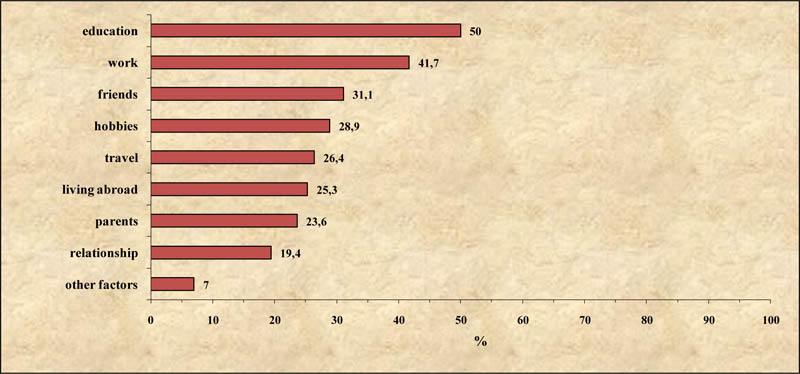

Question 6b was directed only at those respondents who saw themselves as bi- or multilingual, i.e. about 16 % of the respondents. The most common factors influencing the respondents’ bi- or multilingualism were education and work (Figure 4). Other frequent factors were friends and hobbies. Approximately one quarter of the respondents mentioned travel, parents, and living abroad as factors that had influenced their bi- or multilingualism.

As factors influencing their multilingualism, men indicated travel and hobbies more often than women, whereas women indicated

living abroad more often than men. No other differences were found between the sexes (see Table 6b.1). The youngest age group (15–24) was different from the other age groups in many respects (Table 6b.2): in the youngest age group the three most important factors explaining bi- or multilingualism were education, friends, and hobbies, whereas living abroad was clearly a minor factor compared to the other age groups. Among the older age groups work was the most important factor and education the second most important. Between areas of residence the only significant difference was in the option friends, which was a somewhat more important factor explaining bi- and multilingualism among respondents living in large cities, as compared to other areas of residence (Table 6b.3).

FIGURE 4 The distribution for the question “If you consider yourself to be bi- or multilingual, what are the factors that have contributed to this situation?”

The most important difference between levels of education concerned the option work, the significance of which increased with the level of education. A similar phenomenon was found concerning the option living abroad, which was a distinctive factor among respondents with a polytechnic education as compared with lower levels of education. The option friends also showed significant differences between different levels of education. Respondents with a university education mentioned this factor considerably more often than the others (Table 6b.4). Comparisons by occupation showed differences only in terms of education; this factor was mentioned most often by managers and experts, and most rarely by healthcare workers (Table 6b.5).

Overall, education and work appeared to be the most important factors explaining bi- and multilingualism. This would suggest that for the respondents, multilingualism (if possessed) is something “actively acquired”, rather than something absorbed through living in multilingual communities.

3.1.4 Language of basic education

Question 7 was in two parts. Question 7a asked respondents whether they had received their overall basic

education in their mother tongue (see Tables 7a.1–7a.5). Nearly all the respondents (over 98 %) indicated that they had received their basic education in their mother tongue. No statistically significant differences were observed between background variables.

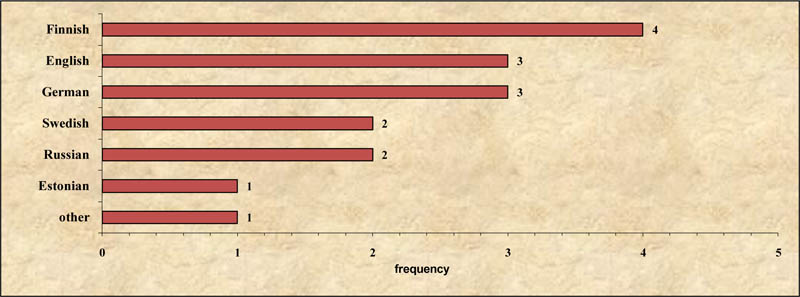

Question 7b was directed only at those respondents (less than 2 % of all the respondents answering 7a; n = 21) who had received their basic education in some language other than their mother tongue. They were asked in what language they had received their basic education, choosing from eleven options: English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Estonian, Sámi, Swedish, Finnish, and other. However, this question was answered by only 16 respondents. The distribution is shown in Figure 5. The language mentioned in the other option was Karelian.

Due to the small number of responses, no comparisons between background variables were made for question 7b.

FIGURE 5 The distribution for the question “What was the language of your basic education?”

3.1.5 Travel abroad

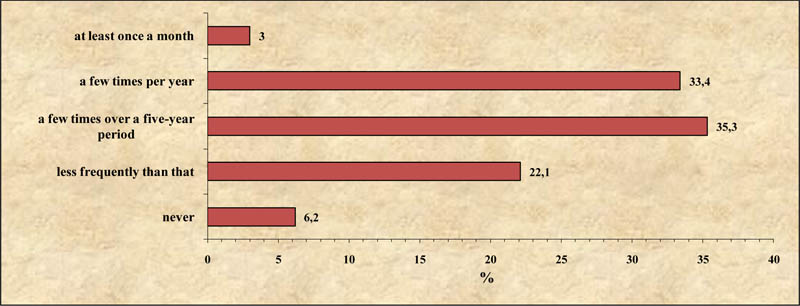

Question 8 concentrated on how often the respondents travelled abroad. With this question we wanted to explore the respondents’ views on situations in which foreign language use, or at least encounters, might occur. The respondents were asked to indicate on a five-point scale (at least once a month, a few times per year, a few times over a five-year period, less frequently than that, or never), how often they travelled outside Finland. They were told to include both work and leisure travel. Only 3 % of the respondents indicated that they travelled very frequently (at least once a month); 33 % said that they travelled abroad a few times per year, and 35 % indicated a few times within a five-year period. Less frequently than that was indicated by 22 % of the respondents, while only 6 % indicated that they never travelled abroad (Figure 6).

The subgroup distributions are shown in Tables 8.1–8.5. There were somewhat more men than women who travelled abroad at least a few times per year. Comparisons between age groups revealed that the 25–44 age group travelled most; the respondents in this age group indicated more frequently than the other groups that they travelled abroad at least once a month or a few times per year. The respondents in the oldest age group were the ones that travelled least. The contrast between age groups can be seen as a sign of a more general change in the society, one that has resulted in great differences between younger and older Finns in terms of internationalisation and international encounters (cf. Dörnyei et al. 2006: 6–7).

FIGURE 6 The distribution for the question “How often do you travel abroad?”

In comparisons by area of residence, the following trend was found: the more populous the area of residence, the more frequent were the travels abroad. Furthermore, comparisons by level of education and occupation consistently demonstrated that the respondents who travel often are highly educated and in managerial positions. Among the managers there were no respondents who never travelled. Most of the respondents who had never travelled abroad were at the lower levels of education and in the manual worker category.

3.1.6 Living abroad and the languages used there

Question 9 was in two parts. Question 9a asked how many of the respondents had lived abroad for a continuous period of at least three months (Tables 9a.1–9a.5). All in all, approximately one fifth of the respondents had lived abroad for at least three months. The proportion was slightly higher among women than men. There were differences between age groups: living abroad was most common among respondents of working age, i.e. among those aged 25–44 (30 %) and those aged 45–64 (21 %). In comparisons by other background variables, it appeared that living abroad was most common among respondents living in cities (29 %), respondents with higher levels of education (50 %), and respondents who were managers (30 %) or experts (39 %).

Question 9b asked about the reasons for living abroad and the languages used during the stay. Only respondents who had lived abroad (22 %, n = 313) answered this question. They were allowed to indicate a maximum of five countries (besides Finland) in which they had lived for a continuous period of at least three months. In addition, the respondents were to mark the reason for living abroad: (studies, work, or other) and the language they had used most during the stay. Note that Finnish is included among these languages, since it might also be used while living abroad. The resulting distributions are presented in Tables 9b.1–9b.6. Since many of the 313 respondents had lived in more than one country, a number of observations are available from these individuals. For this reason, the observations in the tables amount to 453.

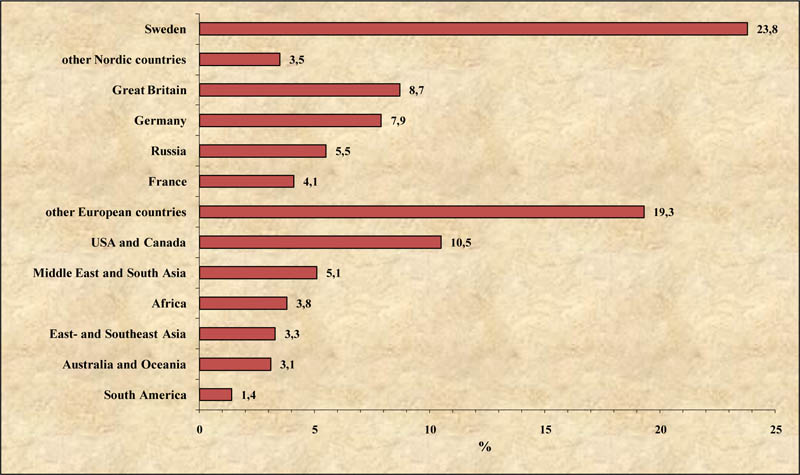

The country that was mentioned most frequently was Sweden: 24 % of the respondents who had lived abroad had lived in Sweden. Next came North America (USA and Canada), Great Britain, and Germany: 8–10 % of the respondents who had spent a continuous period abroad had lived in these countries (see Figure 7 and Table 9b.1). Altogether 61 countries were mentioned, representing all the permanently inhabited continents of the world.

FIGURE 7 The distribution of the countries or continents where the respondents had stayed longer than three months

Table 9b.1 also shows the results on English language use in different countries. As could be expected, in English-speaking countries English was the language with the most use. Among the respondents who had lived in Great Britain, 96 % had used English the most. Among those who had lived in North America, the figure was 93 %, and among those who had lived in Australia or Oceania, 90 %. English was also frequently used by those living in the Middle East or South Asia (78 %) and Africa (64 %). In contrast, English was used significantly less among those living in France (35 %), Russia (19 %), and Germany (16 %), reflecting the high status of the national languages of these large European countries. These languages also have a long history of instruction in Finnish schools. Among respondents who had lived in other parts of Europe, English was used more (54 %) than among those in France, Russia, or Germany, but still significantly less than among those in English-speaking countries.

English was used the least frequently as the primary language in Sweden: out of the respondents who had lived in Sweden, only 5 % had used English as the main language. Thus in our result, the status of Swedish as Finland’s official language and as an obligatory school subject is reflected as a capacity to use Swedish. In other Nordic countries, English had notably greater use (43 %). Other areas where English was used fairly frequently were South America (31 %) and East and Southeast Asia (54 %).

The most common reason for living abroad for at least three months was work. For those who had used English as the main language, the second most common reason to live abroad was studies. However, for those who had used some other language, the second most common reason provided was other reason (i.e. not work or studies). Such a reason might be, for example, living abroad as a teenager with one’s family. Among the respondents who had used English as a main language there was a difference between the sexes: for men the most common reason for living abroad was work, whereas for women it was studies (Table 9b.2).

Among those who used mainly English when living abroad, it emerged that in the 25–44 age group the reason for living abroad was significantly more often studies than it was for older respondents, for whom the reason was most frequently work. In the youngest age group the most frequent reason for living abroad was given as other reason, i.e. not studies or work (Table 9b.3).

Among the respondents who had mainly used English when living abroad, no differences were discovered between areas of residence. However,

the respondents living in large cities were different from the rest in terms of those who had mainly used some language other than English;

among these respondents, other reasons for living abroad were as common as work. In other areas of residence, especially in the countryside, work was clearly the most frequently mentioned reason for living abroad (Table 9b.4).

In comparisons by level of education (Table 9b.5) it was found that studies tended to be the main reason for living abroad among those with higher levels of education. In comparisons by occupation (Table 9b.6) the picture is less clear, with work taking on greater importance among both managers and manual workers.

3.1.7 Foreign language studies

Question 10 asked which languages (excluding the mother tongue) the respondents had studied and in what kinds of learning environments. Eight languages (English, French, German, Russian, Spanish, Italian, Swedish, and Finnish) were given in the questionnaire, but the respondents were also given space to add other languages they had studied. Eleven learning environments were defined:

(a) before school,

(b) compulsory education (7–16 years),

(c) upper secondary school,

(d) vocational education,

(e) polytechnic,

(f) university,

(g) adult education courses,

(h) folk high school (further information Finnish Folk High School Association),

(i) courses provided by employer,

(j) language courses abroad,

(k) self-study.

Out of all the respondents, 90 % had studied some language (see Tables 10a.1–10a.5). The percentage is obviously high and demonstrates the high value placed on foreign language studies in Finland. A slightly higher proportion of women than men had attended language studies. In the youngest age group (15–24), almost 100 % had attended language studies. This proportion decreased with age, so that among the oldest age group (65–79), 70 % of the respondents had attended language studies. However, this figure could still be considered fairly high.

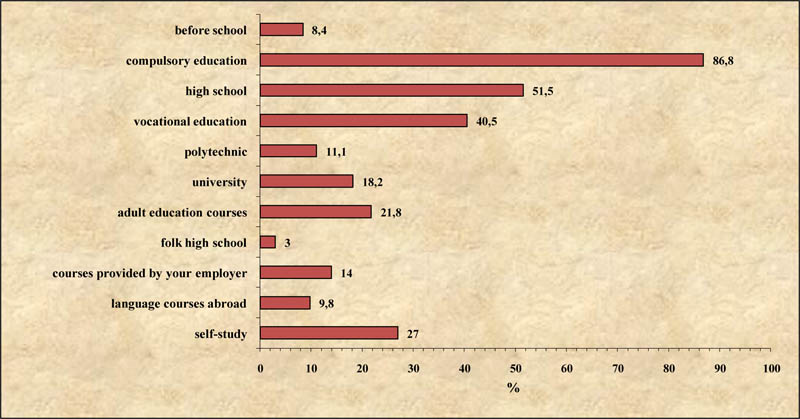

FIGURE 8 The frequencies of language studies according to different contexts and stages of life

Comparisons by area of residence showed that the number of respondents who had studied at least one language increased as the focus moved

from the countryside to the cities. However, it should be noted that no less than 81 % of the country dwellers stated that they had taken

part in language studies. The proportion of those taking part in language studies rose with the level of education, and also with occupation. Only 52 % of the respondents with the lowest level of education had studied at least one language, whereas among those with lower secondary education the rate was 85 %, and among those with higher levels of education 100 %. Among experts and managers the rate was close to 100 %, whereas among office and customer service workers, and also healthcare workers, the rate was approximately 90 %. Among manual workers the rate was 77 %.

Language studies at different life stages and in different contexts are presented in Figure 8. The corresponding distributions by background

variables are shown in Tables 10b.1–10b.5. In Figure 8, all the languages mentioned by the respondents are included, with the percentage values calculated only for those respondents who had attended language studies (90 % of all respondents; n = 1 342). The figure reflects how the respondents were educated in general; also how many attended upper secondary school, polytechnic, etc. It shows that more than one quarter of the respondents had studied some language via self-study, and more than one fifth done so via adult education courses. Language studies before school age seem to be uncommon.

Comparisons by gender revealed that it is more common for women than men to attend language studies at upper secondary school, adult education courses, folk high school, and at language courses abroad (Table 10b.1). No other differences were found between the sexes. Comparisons by age group showed several statistically significant differences (Table 10b.2). The most important result was that the youngest age group had attended language studies before school and during compulsory education more than the older age groups, whereas the older age groups had studied in adult education courses more often than the younger age groups. Self-study was roughly equally frequent among all age groups.

Comparisons by area of residence (Table 10b.3) also showed significant differences in all categories, except for folk high school. Again, cities stood out: in them the proportion of respondents who had attended language studies was consistently the highest. The only exception was vocational training, in which the situation was the opposite. The result does not merely give information on foreign language studies; it reflects the different types of educational processes in different types of area: in the adult population, the proportion of those with vocational education is greater in small municipalities than in cities.

Differences relating to levels of education (Table 10b.4) are generally as expected. Interestingly, the respondents with the highest levels of education were also those who were most likely to have attended language studies outside their main educational setting: in adult education courses, courses provided by the employer, language courses abroad, or self-study. Similar results were discovered in comparisons by occupation (Table 10b.5). Overall, language studies were most infrequent among manual workers.

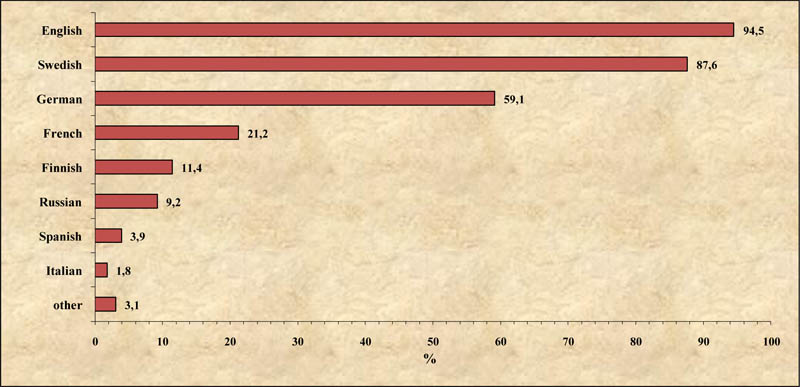

The frequencies of studies in different languages in relation to the educational environments given in question 10 are presented in Table 10b.6. English was the most frequently studied language, with no exceptions. Not surprisingly, in schools and other educational institutions Swedish had a high frequency of study. The third most frequently studied language tended to be German, which was studied in a wide variety of educational settings, from basic education to university. Before school Finnish (as a second language) was studied relatively frequently.

FIGURE 9 The frequencies of language studies in upper secondary school

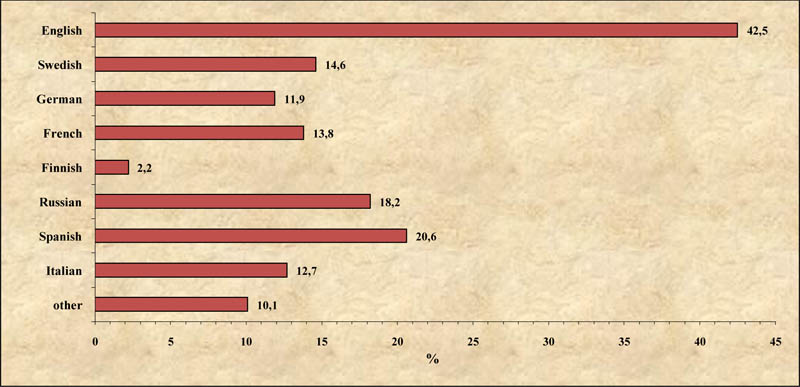

FIGURE 10 The frequencies of language studies in adult education courses

For exemplification purposes, Figure 9 presents percentage values for different languages studied at upper secondary school. In other educational institutions the situation is roughly the same. The clearest exception is adult education courses, where people often go to learn languages that have not been part of their basic education (Figure 10). Nevertheless, English was also the most studied language in this environment.

To make comparisons easier, the columns in Figure 10 are presented in the same order as in Figure 9. Compared to the languages studied at upper secondary school, we immediately observe decreased study percentages for Swedish and German, and increased percentages for Spanish, Russian, and Italian.

French was studied most commonly at university and upper secondary school, whereas Russian was studied in adult education courses, at university, as self-study or in courses provided by the employer. In adult education courses, folk high school, university, or self-study, Spanish was studied frequently (Table 10b.6).

The distributions of English studies by different background variables can be seen in Tables 10b.7–10b.11. These mainly resemble the distributions for foreign language studies in general (Tables 10b.1–10b.5). Nevertheless, some interesting points emerge. Among men, English studies before school and in self-study have higher percentages than among women. No such tendency was discovered in relation to language studies as a whole. Another interesting finding concerned language studies in adult education courses. When studies of English are compared to language studies in general, the proportions of managers, respondents with a higher level of education, and city residents are significantly lower. This would suggest that for the above groups it is more common to study languages other than English in adult education courses. Managers in particular (after their main education) study English more often via (i) self-study, (ii) courses provided by the employer, or (iii) language courses abroad than via adult education courses.

3.1.8 Uses of foreign languages

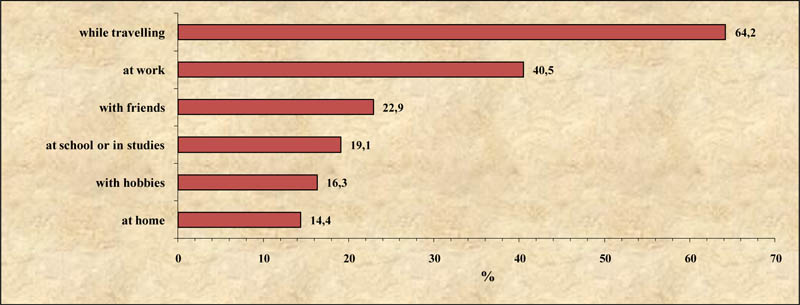

Question 11 asked respondents to indicate in which contexts (work, school/studies, home, hobbies, friends, travel) they used the foreign languages mentioned in question 10 (English, French, German, Russian, Spanish, Italian, Swedish, Finnish, or other). The respondents could also indicate that they used only their mother tongue, and move on to the next question. The respondents were told to include even minor amounts of speaking, reading, and writing, and not to count mother tongue usage. The distributions can be seen in Tables 11.1.1–11.6.5. Approximately 12 % (176 respondents) indicated that they did not use languages other than their mother tongue in the contexts offered.

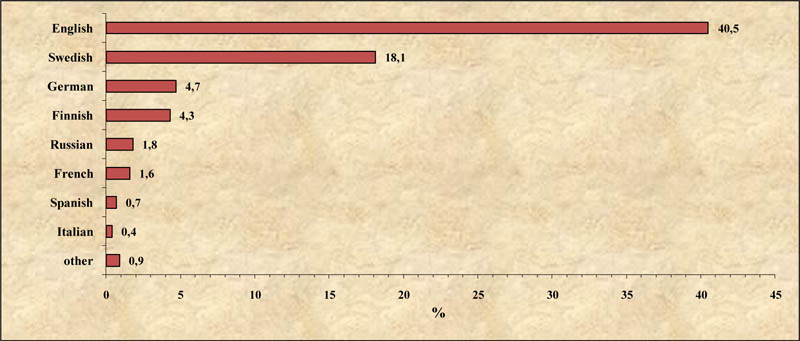

Out of the options given, foreign languages were most frequently used in travel, and second most frequently at work. In all the options, English was the most commonly used language, and Swedish the second most common. The third most commonly used foreign language was usually German. However, the uses of German or other languages were minor compared to the uses of English or Swedish. As an example, Figure 11 shows foreign language use at work. The distributions for foreign language use in the contexts school/studies, home, hobbies, and friends are largely similar to those for Figure 11, but with lower percentages. The percentage for the use of Finnish is approximately equal to the proportion of respondents with some language other than Finnish as their mother tongue.

FIGURE 11 The frequencies of using foreign languages at work

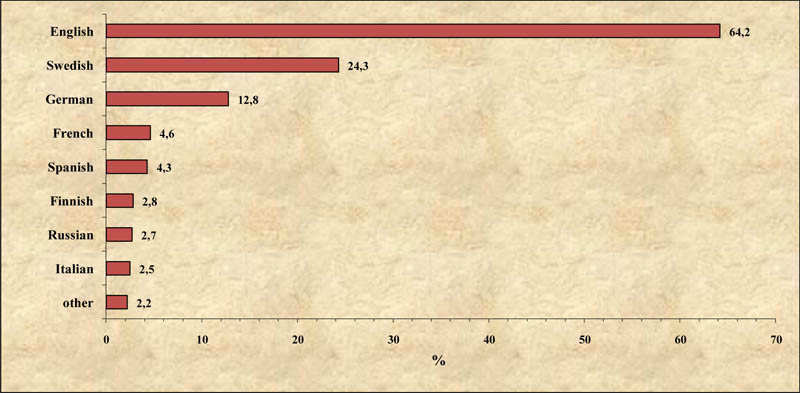

FIGURE 12 The frequencies of using foreign languages while travelling

The use of foreign languages in travel showed some differences from the other contexts. The response distributions are shown in Figure 12. It is noteworthy that the use of German has increased in comparison to the other contexts, and that French and Spanish are more commonly used than Russian and Finnish in this context.

Because English and Swedish are used significantly more often than other languages in all contexts, the use of those languages was now studied by gender, age, and other background variables. Figure 13 presents the use of English in the contexts offered.

FIGURE 13 The frequencies of using English in different situations

When the use of English was compared between the sexes (Tables 11.1.1–11.6.1), we discovered that women use English significantly more often in travel, whereas men use English more often in connection with hobbies. In other contexts there were no significant differences between the sexes.

The differences between age groups were significant in all contexts (Tables 11.1.2–11.6.2). At work, English was naturally used most by persons of working age, and in school/studies by younger respondents. In addition, the youngest age groups used English in the contexts home, hobbies, friends, and travel more often than the older age groups, although the difference was not large in the travel case. In this sense English seems to play a greater role in the everyday life of young Finns than it does with older Finns.

Comparisons by area of residence showed significant differences in all contexts (Tables 11.1.3–11.6.3): city-dwellers used English more often than the others. The differences between residents in towns, rural centres, and the countryside were usually minor.

The use of English increased with the level of education, and this applied to all contexts (Tables 11.1.4–11.6.4). The use of English in school/studies was emphasised not just in the answers of those with a university education, but also among respondents with a lower secondary education. Because a large proportion of the youngest age group is included in this category, the result reflects the active use of English among young people.

In comparisons by occupation, experts stood out as the most active users of English (Tables 11.1.5–11.6.5). Manual workers and healthcare workers used English least at work, while healthcare workers used English least with hobbies. Managers said they used English at work and with friends just about as frequently as experts.

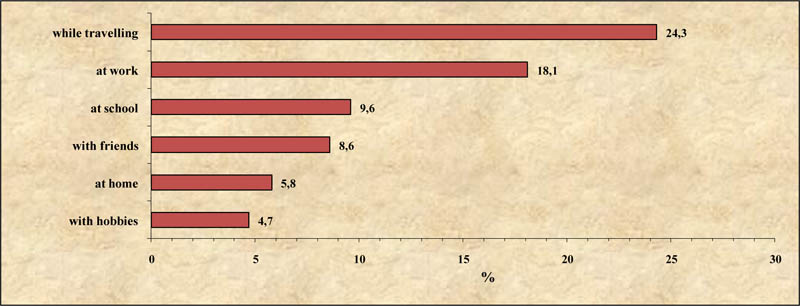

Figure 14 presents use of Swedish in different contexts. Like English, Swedish was mostly used at work and during travel, but significantly less frequently. Comparisons by background variables (e.g. age and level of education) lead to the same conclusions which were earlier made regarding English use: the use of Swedish is most common among the youngest age group, residents of large cities and those with higher levels of education. Experts and managers stood out among the occupational groups. Comparisons by gender revealed that women use Swedish more often than men in travel, and in school/studies, whereas men use Swedish more often with hobbies. Other contexts showed no significant differences between the sexes.

FIGURE 14 The frequencies of using Swedish in different situations

Finally, we focused on the respondents who indicated that they used their mother tongue only (12 %). Here, the proportion of men (14 %) was

slightly higher than the proportion of women (10 %). This group was well represented by the oldest age groups, country dwellers, respondents with a low level of education, and manual workers. As many as half of the respondents with the lowest level of education said they used only their mother tongue (Table 11.1.4).

3.1.9 Foreign languages in the Finnish environment

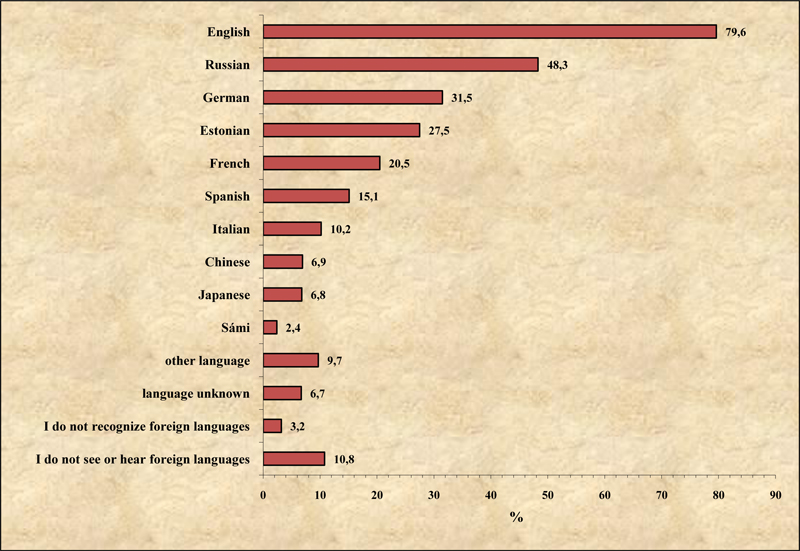

Question 12 asked what languages the respondents heard and saw in their environment. The idea was to investigate the presence of different languages in the respondents’ lives, as they saw it. Ten language options were offered (English, French, German, Russian, Spanish, Italian, Sámi, Estonian, Chinese, and Japanese). It was also possible to mention “some other language”, and to indicate having seen or heard unfamiliar foreign languages. The respondents were asked to exclude Finnish and Swedish. The distributions are seen in Tables 12.1–12.5.

There were 161 respondents (11 %) who indicated that they did not see or hear foreign languages. This group included many elderly respondents and country dwellers. In addition, the level of education in this group was often very low. Approximately 3 % of the respondents indicated that they did not recognise the foreign languages they encountered in their surroundings. As in the previous category, this group included mainly elderly respondents or respondents with a low level of education.

FIGURE 15 The frequencies of seeing or hearing different languages in the respondents’ surroundings

The foreign language that was clearly seen or heard the most in the respondents’ surroundings was English (80 % of all the respondents, see Figure 15). If we exclude the respondents who indicated that they did not see or hear foreign languages, the proportion for English rises to 89 %. Second comes Russian (48 %) which has a clear lead over the third and fourth most commonly encountered languages, German (32 %) and Estonian (28 %). Again, if we exclude the respondents who did not see or hear foreign languages, we can estimate that more than half of the Finnish population encounter Russian in their surroundings.

Only minor differences were discovered between the sexes in terms of encountering foreign languages (Table 12.1). In general, women indicated having encountered foreign languages more often than men, but a statistically significant difference was detected only in three languages; these were French and Chinese, plus the other language category (i.e. other than the languages given as options).

Differences between age groups were nearly always highly significant (Table 12.2). Respondents in the two youngest age groups (15–24 and 25–44) seemed to encounter foreign languages in their environment more than the older age groups: for almost every language given as an option, the two youngest age groups had the highest percentages. This probably reflects the greater language awareness (resulting from language studies) and the greater mobility of the younger population (cf. question 8, according to which those in the 25–44 age group travel abroad more frequently than the others). Those who had not encountered foreign languages or did not recognise them mostly belonged to the oldest age group.

Russian and Estonian stood out from the other languages to some extent: seeing or hearing these languages was most common among the two mid-range age groups. In the oldest age group, too, encounters with these languages (as well as with English) were relatively common.

Comparisons by area of residence (Table 12.3) revealed that foreign language encounters took place more often in cities than in the countryside. In all areas of residence, English was the most frequently seen or heard language, and Russian the second most common. No significant differences were found between these two languages in either large or smaller cities. By contrast, German, Estonian, French, Spanish, and Japanese were clearly encountered more often in large cities than in smaller cities.

As expected, comparisons by level of education (Table 12.4) indicated that encounters with foreign languages correlate with the level of education. Among the least educated respondents, 14 % indicated non-recognition of foreign languages, and 26 % said they did not encounter them in their environment. Because occupation and level of education are closely linked with each other, the distributions by occupation (Table 12.5) lead to similar conclusions. Managers and experts, who are usually highly educated, encounter foreign languages more often than (in particular) manual workers. Furthermore, healthcare workers reported encountering foreign languages relatively infrequently.

3.2 Summary and discussion

The language distribution of the survey corresponds well to the distribution of languages among the Finnish population: Finnish-speakers constituted a substantial majority (94 %), Swedish-speakers around 5 %, with Russian-speakers making up a small proportion. There were very few speakers of other languages among the respondents.

In the light of our results, it can be said that the majority of Finns see themselves as monolingual. This emerges particularly clearly among elderly respondents, country dwellers, and persons with low levels of education. Monolingualism is also demonstrated by the fact that general basic education is almost without exception received in the mother tongue. The self-perception of bi- or multilingualism was most common among young respondents and well-educated city residents. As the most important factors influencing bi- and multilingualism, education and work were emphasised, as were friends among the youngest age groups. In addition, the respondents’ families were mainly monolingual. In cases where this did not apply, the family was most likely to be fairly young, living in a city, and highly educated. In the light of these results, Finland emerges as comparatively monolingual, with “actively acquired” multilingualism being found particularly among young, highly educated, city residents, and persons in managerial positions.

Finns travel abroad frequently: only 6 % of the respondents claimed that they did not travel at all. Travel naturally increases foreign language encounters, and it also increases foreign language use. English and Swedish in particular were mentioned as languages that are used during travel.

The most active travellers are aged 25–44, residents of large cities, and highly educated. Those travelling the least are elderly people, those living in the countryside, and those with less education. Travel thus presents a picture similar to that for multilingualism. More than one fifth of the respondents had lived abroad for at least three months. The most common destination mentioned was some European country, especially Sweden, though the USA and Canada were also mentioned quite frequently. Work is the most frequent reason for living abroad. In most countries the most commonly used foreign language during the stay was English. Germany, Russia, and France and particularly Sweden stand out as countries where English is used less often than elsewhere. It is evident that in these countries the respective national languages are used most.

According to the survey, 90 % of Finns have studied or are currently studying at least one foreign language; even among the oldest respondents the figure reached 70 %. The rates demonstrate that foreign language skills are seen as important in Finland, and that people apply themselves to language study at all levels of education. English is studied the most, and Swedish to almost the same extent. German, too, has a relatively high share in our data. Yet even though language studies involve the whole population, some differences can be found: languages are studied more by the young than the elderly, by women more than men, by city dwellers more than country dwellers, by highly educated people and experts more than others. Languages are naturally studied in formal education, but voluntary studies in adult education courses and self-studies also show a high frequency. The results suggest that in a small language area such as Finland, people are basically more willing to learn languages than in e.g. Great Britain, Ireland, France, Spain, or Italy (Eurobarometer 2006).

As was earlier mentioned, only 12 % of the respondents said that they did not use any language except their mother tongue. That would indicate that the majority of the respondents do use some other language, at least sometimes. At work, English is used more frequently by men than by women, and also by residents of cities, managers, experts, and those with the highest levels of education. Overall, the demands of the increasingly global knowledge economy are reflected in the increasing use of English in working life (cf. Alatalo 2006; Virkkula 2008; Virkkula & Nikula 2010). The youngest age groups again stood out in foreign language use: in comparison with the other age groups, they use significantly more English in the contexts friends and hobbies. This demonstrates that these age groups have more contacts with speakers of foreign languages. However, in the lives of young people English is also a language employed in social and leisure activities, used among Finns as well (see e.g. Leppänen et al. 2008).

Finns do not merely study and use foreign languages; they see and hear them in their everyday surroundings. English is clearly the most frequently encountered language – it was mentioned by 80 % of the respondents. City residents in particular reported encountering English frequently. The visibility of English demonstrates its global status, and the way in which it finds its way to Finnish society through various channels – for example via the practices of (internationalising) working life, the Anglo-American entertainment industry, and the global economy

(Leppänen & Nikula 2008).

After English, Russian is the second most seen and heard foreign language. This is probably due to Russians being more visible in Finland

than before, as a result of increased immigration and tourism. It may also be the case that Russian is perceived more easily than other languages both because of its unfamiliarity (the Cyrillic alphabet) and because of ambivalent attitudes towards Russia and Russians. The respondents also indicated that they heard and saw German, French, Spanish, and Estonian fairly frequently. Thus, Finns, despite mainly viewing themselves as monolinguals, seem to live in fairly multilingual surroundings: various languages are present even if they are not actively used. Nevertheless, encounters with and recognition of foreign languages demonstrate a somewhat uneven division in Finnish society: those who do not recognise foreign languages, or who do not see or hear them, are typically older people with the lowest level of education, living in the countryside. Language encounters, and also language awareness (to the extent of being able to tell one language from another), are more common among well-educated, city-dwelling young adults. This corresponds to the situation in, for example, Denmark, where according to Preisler (2003: 123–124), there is a societal division between those who know and those who do not know English (the “haves” and the “have-nots”).

As a conclusion, we can state that even if Finns view themselves as monolinguals, foreign languages have a visible role in their lives: languages are studied a lot, they are used especially while travelling and in working life, and they are encountered as a part of the everyday environment. English is without a doubt the language with the strongest position among foreign languages: it is the most commonly studied, used, and encountered language. However, the respondents’ backgrounds have a clear influence on how strong the position of English appears. The most influential background variables are (i) age, with young respondents having more dealings with English, e.g. through the media, entertainment, and information technology (Leppänen et al. 2008), and (ii) level of education, which naturally correlates with language skills, language use, and language encounters. The area of residence also has a clear influence (with foreign languages and internationalism being most strongly present in cities); however, it is difficult to say to what extent this reflects the differing population structures of different areas (concerning e.g. age and level of education), and to what extent it involves “genuine” differences between urban and rural cultures/ways of life. Occupation has an influence as well, but it is closely linked with education, area of residence, and gender. In the following chapters we shall deal with the results provided by the questions concerning English in particular.

Back to top

|

|