9 DISCUSSION

The growing significance of English in Finland springs partly from a range of socio-historical factors unique to Finland, and partly from wider processes of economic and cultural globalization. The lives of individuals, social groups, institutions, businesses, and even entire societies are characterized more than before by mobility, diversity, and connectedness. In such a situation there is a heightened need for a vehicular language which will allow communication in circumstances where there would otherwise be no shared code. But globalization affects people’s language uses in other ways as well: people in many parts of the world now engage in global cultural activities associated with, for example, popular music, film, and sports – subcultures in which English serves as an important resource for identification, participation, and cultural production.

Against this background, what happens in Finland is one example of what happens in many other parts of the world in which English originally had no role, but in which it is now needed as a means of communication and/or as a semiotic and socio-cultural resource. In the same way, the Finnish case also illustrates how periods of intense social, cultural, and economic change can ignite deep concerns within us: we feel that something which is dear to us and which defines who we are – in terms of our culture, tradition, heritage, language – is endangered by changes of this kind. In Finland, such concerns have resurfaced in the recent revival of language ideological debates, and in the voices raised in favour of changes in national and institutional language policies. For these reasons, what Finns think about English can give insights into the complexities of sociolinguistic change not just in Finland but also in other parts of the world – places where the impact of English in an originally non-Anglophone context has grown, and where English is simultaneously desired and feared, coveted and shunned.

The present survey sought to examine the use, importance, and status of English through the eyes of Finns, and to find out how they perceive the role of English in Finland. It gives an overview of how Finns encounter, know, and use English, with insights also into their attitudes towards English and how they envisage the future of English in Finland. The survey consisted of six thematic parts: (1) Languages in the respondents’ lives (2) English in the respondents’ lives, (3) studying and knowing English, (4) uses of English, (5) English alongside the mother tongue, and (6) the future of English in Finland.

In this chapter, we shall summarize and discuss the main findings of the survey. We shall do this by structuring our discussion around five core observations which emerged in the study. These involved language attitudes (see 9.1 below), skills and uses of English (see 9.2), language identity in change (see 9.3), differences between social groups (see 9.4), and predictions for the future (see 9.5).

9.1 Language attitudes

The survey shows that the majority of the respondents (80 %) have considerable faith in the stability and vitality of the two national languages and Finnish culture in general. Thus, they do not consider English a threat in this regard (see Table 19.1). In comparison to the attitudes in many other non-English speaking countries, such as Sweden (see Berg et al. 2001) and France (Martin 2006), Finns appear to take a more relaxed view. A belief in the vitality of the national language/s resonates with traditional and pervasive language ideological assumptions in Finnish society concerning the relationship between language and the nation state. In other words, Finns still see language as a cornerstone of Finnish national identity.

Ever since the early days of Finnish nationalism in the 19th century, Finns have been accustomed to view their own language/s and culture as the best protection against a foreign threat (see also Leppänen & Pahta, forthcoming). To think otherwise – to see the languages of Finland as under threat – would mean considering national independence, sovereignty, and integrity to be in serious danger. Apparently, according to the respondents in our survey, this is not the case at all. An interesting point here is that although Finns consider their own languages and culture to be well protected and safe, they are far less optimistic about other countries, cultures, or languages, which are thought to be more susceptible to the negative impact of English. Such conflicting attitudes to English within and outside Finland reflect the complex and contradictory nature of the processes in play in globalization and postmodernity (see also Graddol 2006: 21).

It seems that insistence on the protection of national languages, strongly advocated in many other countries facing the impact of English, is not a crucial concern for Finns (cf. Kubota 2002), even if the survey revealed areas of ambivalence concerning the future (see 9.5 below). Broadly speaking, the respondents’ views on the current situation were at odds with what has been suggested, for example, in the recent language policy programme put forward by the Research Institute for the Languages of Finland (Hakulinen et al. 2009). According to this programme, in a number of societal domains, including science, academic publishing, and higher education, the Finnish language is now in competition with English. Thus it is argued that active protective measures are needed to enforce the right of Finnish citizens (stipulated by the Finnish language law) to use and be served in their own language (ibid.: 11–12). Here one can see a dichotomy: that while the general public expresses permissive attitudes to English, language policy makers – perhaps partly due to their awareness of such attitudes – see a genuine, and harmful, process of change under way. Finns, they believe, need to be aware of the situation and to take measures in all domains of society to protect, promote, and actively prefer their own language over English.

In addition to their trust in the vitality of the mother tongue, Finns have an open, liberal, and interested attitude to other languages and to studying them. They frequently see and hear foreign languages in their everyday lives, and in certain settings they also need to use them actively. Such settings, for example travel or work, often involve some form of international contact. Although English has been studied at least to some extent by all the generations investigated in this survey, and although it is the language that Finns most commonly come into contact with, it is not the only language that Finns are interested in. Many share the view that it is not enough if everyone knows English, and that other languages, too, need to be known.

It is interesting that attitudes to Swedish, for instance, seem quite positive – bearing in mind the current polarized public debate in Finnish society concerning the position of Swedish. In this debate, those against Swedish argue, for example, that the requirement for all students to study Swedish at school reduces their capacity to study other foreign languages. The opposing view emphasizes the bilingualism of Finland and insists that society should maintain the linguistic rights of Swedish-speaking Finns, at the same level as those of Finnish-speaking Finns (see also Salo, forthcoming).

Highly educated Finns in particular, and those in expert positions, tend to be of the opinion that Finns should learn other languages in addition to English. The same point is made by Kankaanranta & Louhiala-Salminen (2010), who have studied the use of English in work settings. The positive attitudes of the survey respondents towards other foreign languages may also derive from the particular position of Finns as speakers of two small languages: they have always seen foreign languages as an important means of communication with the rest of the world (Numminen & Piri 1998). Without foreign languages, Finnish society, business, and individuals would undoubtedly be handicapped in international contacts and communication.

This general emphasis on the importance of a broad language repertoire is, nevertheless, in conflict with recent developments at all levels of language education in which the dominant position of English has continued to strengthen over recent decades. Because of limited resources, optional languages (the A2 languages) are fairly seldom offered or chosen in schools (partly because of the fairly large minimum group sizes required), and overall, language studies in upper secondary schools have been reduced (e.g. Hämäläinen et al. 2007). Despite the generally positive attitudes to foreign languages, language education as a system is thus unable to satisfy the needs of Finns as potential learners of not just one, but many foreign languages. As one possible solution to this, it has been suggested that English studies should actually be reduced in schools, on the grounds that the language is in any case widely available. In this way the teaching of other foreign languages might gain more resources. However, over the long term, such a solution could mean that Finns have even fewer opportunities to learn any foreign language well. Moreover, they would no longer have the possibility to acquire the kind of sophisticated proficiency in English that is now needed, for example, in many work contexts. The survey results give support to this conclusion: only 16% of the respondents were of the opinion that they had acquired their English proficiency outside formal language lessons. Hence it seems likely that reducing the number of language lessons would seriously jeopardize students’ possibilities to achieve high proficiency in English.

9.2 Skills and uses of English

One key finding of the survey is that, according to their own self-assessment, Finns have relatively good skills in English: about 60 % are of the opinion that their proficiency is at least relatively good. On a general level, this figure is considerably higher than, for example, recent Eurobarometer (2006: 14) results, according to which only 38 % of EU citizens think they have sufficient skills in English to engage in a conversation. Here it should be pointed out that overall, Finns do not actually use English that much, at least on a daily basis. Nevertheless, there is considerable variation according to the background variables, both in the proficiency and in the use of English.

As regards their proficiency in English, Finns rate their receptive language skills higher than their active uses of the language, i.e. in writing and speaking (see also Bolton & Luke 1999). They report that they have obtained their skills mainly in formal lessons, but to a great extent also elsewhere. Despite their good English skills, a high proportion of the respondents nevertheless feel inadequacy, at least in some situations. This was a particularly common concern among respondents who need to use English in their work, such as managers and experts. Similar feelings of inadequacy have been reported by Finnish engineering students in a qualitative study by Virkkula & Nikula (2010): these students felt that their knowledge of grammar and vocabulary was not enough to communicate well in English. In fact, this finding is not really surprising, given the increasingly common use of English, for example in working life, where people have to cope in increasingly demanding situations of language use (Louhiala-Salminen et al. 2005).

Another interesting finding was that even though Finns rate their proficiency in English as relatively high, almost all the respondents wanted to improve their skills – presumably because they are aware that their proficiency is not good enough in all communicative situations. All in all, Finns seem to be fairly modest about their language skills: they feel that they have good skills but that there is always room for improvement. In the light of these findings it seems that one of the challenges for language educators is to provide Finns with both an adequate level of “civic skill” in English, sufficient to manage in most everyday situations, as well as more sophisticated skills for those who need to be able to deal with demanding situations. It seems that a revised plan for language education is called for, covering all levels and sectors of the system. This plan could specify what language skills are the target at every level and sector of the educational system, ranging from basic education to higher education and to workplace learning. One can envisage a continuum in which the learners’ changing needs and varied target levels are accommodated in a more systematic way than is possible with the current system – which is largely based on the replication of the same core skills at each level.

Even though people are increasingly aware of the presence of English in the Finnish linguistic landscape, it is far from the case that all Finns use English actively in their daily lives. In view of the sometimes heated public discussion on the spread of English in different domains, it is rather surprising that, according to our results, Finns’ use of English is not very extensive. In fact, compared to the average among EU citizens, Finns’ uses of English are fairly limited. Thus, while the Eurobarometer (2006: 16) reported that 31 % of EU citizens use English almost daily, our survey suggests that the daily use of English in Finland is still quite rare (e.g. only about a fifth of the respondents report speaking it at least once a month).1

A closer look at the times and places in which English is used by Finns shows that it is used most often in free time, but also at work, with young respondents the most active users. Overall, the active use of English is a good deal less common than listening to English-language music, watching films and TV programmes, reading websites, e-mails and manuals, and searching for information on the internet. Writing in English is infrequent in most population groups, but it does occur among young people in the context of the new media. The most common reason for using English seems to be searching for information. Other frequently mentioned purposes include using English just for the fun of it, for everyday interaction, and for language learning. However, the survey also indicates that when Finns actually need to use English actively these situations most often involve some kind of international contact. Overall, it would seem that Finns are not shifting to English in their mutual communication and interaction (but note the remarks on code switching, below). For most purposes, Finnish and Swedish are still sufficient. Against this background, situations in which English is selected as the group- or company-internal language of communication are still fairly exceptional.

At the same time, it is also quite clear on the basis of our survey that English is definitely the most important foreign language to Finns. It is considered more important than Swedish, but less so than the mother tongue. It is the foreign language that Finns encounter most frequently in their everyday lives, and the language they are able and willing to use with most ease. In some domains, such as science and popular culture, it is often seen as even more important than Finnish. Especially for young, urban, and educated Finns, it is also increasingly one of their everyday language resources – a resource which they use without hesitation in situations where they would not get by with their first language. In the same vein, Finns’ attitudes to mixing their first language with English are quite positive (cf. Kamwangamalu 2002; Hussein 1999), especially when it occurs in informal oral communication with friends or workmates. In such situations code switching often occurs quite naturally, without the speaker even noticing it, and with the hearer decoding it quite easily. Finns’ attitudes to English are thus generally positive and pragmatic: its use as a language of education, working life, and international interaction is generally approved of, and English skills are viewed as important to nearly all population groups.

9.3 Language identity in change

Even though Finnish society is officially bilingual in Finnish and Swedish and Finns speak English relatively well, as individuals they consider themselves monolingual. The reason most likely has a great deal to do with the fact that among Finns, partial command of a foreign language is not identified as bi- or multilingualism. Their view is rather that to be fully bi/multilingual, one needs wide-ranging, native-like language skills. Native speakers of English are admired because of their supposed complete proficiency, and their good language skills are set as the goal in language learning, although there is a sense that this goal can never be fully achieved. Hence, although English is a fairly familiar language, the majority of the respondents do not find it as natural to use English as it is to use the mother tongue. In a sense English is viewed as “distant”, as belonging mainly to native speakers and not as part of Finns’ own language repertoire. In other words, for many Finns it is still primarily a foreign language – one which is studied, enjoyed, and occasionally even used, but which is primarily needed in communication with people with whom no other language is shared.

For most learners, the goal of achieving some ideal of native-speaker competence – supposing such a thing existed – is probably not the best option. Here again lies a challenge for language educators. In the future, they may have to persuade learners that a realistic standard of proficiency in English is not native(-like) competence – since no native speaker’s competence is ever perfect either – but the competence to cope in situations that learners feel are important, without discarding their identities as Finnish users of English. Such a competence would be a much more reasonable target in a globalized world, in which people’s language competences are always in one way or another truncated, contextual, or organized topically on the basis of domains or specific activities (see e.g. Blommaert 2005, 2010; Haviland 2003; Urciuoli 1996).

In the same way as was shown in a study focusing on the presence of English in the lives of young people in Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands (Berns et al. 2007), the present survey indicates that young people form an exception to the general picture. Their responses show very clearly that English is beginning to have an integral role in their lives. It is increasingly part of their language repertoire, social relationships, hobbies, and interests. For many, it also is a means of verbalizing their emotions, and sometimes even an essential factor in the construction of their identities. Why this is the case has undoubtedly a great deal to do with the increased presence and importance of English in youth cultures and sub-cultures. These have offered young people meaningful socio-cultural arenas within which English functions as a resource for self-expression and communication in culturally and socially meaningful ways. In addition, the rapid development of information and communication technologies, which have brought about sophisticated social media (Kangas & Kuure 2003; Nurmela et al. 2004; Androutsopoulos & Beißwenger 2008), has also created new channels of interaction in young people’s lives; English is increasingly a readily available resource for expression and interaction, irrespective of one’s place of residence (see Leppänen et al. 2009b). It could even be argued that popular cultural movements and flows, including also ICTs, constitute an important historical factor contributing to the relevance of English to many young people (Leppänen, forthcoming).

9.4 Differences between social groups: Haves, have-nots, and have-it-alls

As has become evident in the results presented in this report, there are interesting differences concerning how well different demographic and social groups know English, how they use and need it, and how they feel about the presence of English in Finland. These differences derive from their varied relationships with English: their learning of, exposure to, and need for English. They are also interesting in the way they can lead us to consider the implications for participation in society in more general terms.

One way of characterizing respondent groups with different profiles vis-à-vis English is suggested by Bent Preisler’s study of the status of English in Denmark. On the basis of his survey findings, Preisler (2003) distinguished two respondent groups: the “haves”, those who know English and use it, and the “have-nots”, those who do not know it and therefore do not have access to the language use and communication that takes place in English.

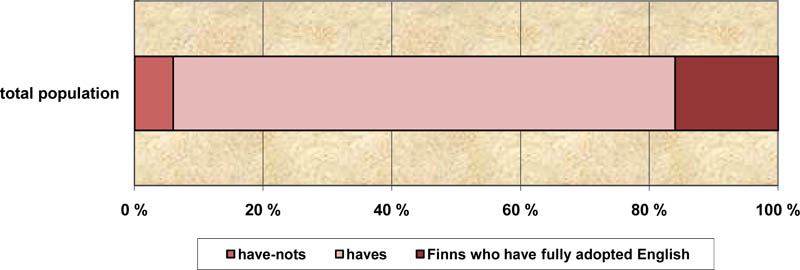

In the same way, in the present study we have repeatedly noted the fact that the majority of Finns have studied English and that Finns rate their English skills quite highly. Hence, the majority of Finns belong to the “haves” in one way or another. However, in this study the line between the “haves” and the “have-nots” is not as clear-cut as in Preisler’s Denmark at the beginning of the new millennium. This is because the responses to the questions on English studies, skills, and use (i.e. questions 21–34) revealed, not a clear division between two groups, but a continuum of different orientations. At one end of the continuum there is a small group of Finns who are totally uninvolved with English (approximately 6 % of persons aged 15–79, according to our data), and at the other end a larger group of Finns (approximately 16 %) who have fully adopted English, and in whose life English has a significant role (Figure 62).2 The majority of the respondents (approximately 78 %) are involved with English in one way or another, and because of the size of the group, they have a dominant position in the results that concern the population as a whole.

FIGURE 62 The percentages of “have-nots”, “haves”, and “have-it-alls” in the total population

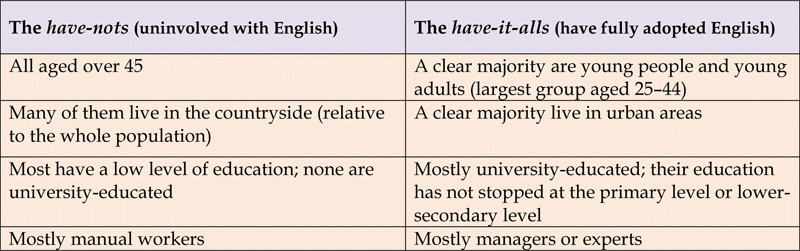

Thus Finns can be roughly placed into three groups (on the continuum) each reflecting a particular relationship to English. Extending Preisler’s categories, these groups are here called the “have-nots”, the “haves”, and the “have-it-alls”. Respondents were classified as “have-nots” if they met all the following criteria: they have studied English for less than five years or not at all (10 % of the respondents); they speak, write, and understand English no better than poorly (24 % of the respondents) according to their own estimate, and they do not use English at all (11 % of the respondents). Finns who have fully adopted English (the “have-it-alls”) meet all the following criteria: they have studied English for more than ten years (29 % of the respondents), they are of the opinion that they speak, write, and understand English well (26 % of the respondents), and they use English frequently (58 % of the respondents).

The largest group, the “haves” – those who are involved with English in some way or another – is more heterogeneous than the two extremes, and, unlike them, cannot be characterized via distinct criteria. For example, they may have studied English for several years and feel they know it relatively well, but still practically never use it. These three groups also differ from one another clearly in terms of age, area of residence, education, and occupation. Some of the tendencies that distinguish the extremes from each other are summarized in Table 12. (It should be noted that the majority of the population belong to the main group formed by those who are in some way involved with English; hence this group includes demographic and social group characteristics in approximately the same ratio as in the whole population.)

TABLE 12 A society divided by knowledge and use of English

The group of “have-nots” (about 6 % of the total) consists of older respondents, often living in the countryside (40 % vs. 20 % among the total population), with a low level of education (over 80 % having primary or lower secondary education only), and doing mainly manual work (70 %). Those in the group of “have-nots” do not know any English; they do not use it and as far as they are concerned they do not need it. Hence, English means very little to them. In this group it is also more common than in the other two groups to see oneself as monolingual: as many as 93 % of the respondents in this group described themselves in this way (vs. 84 % for the total population). The lifestyle of these respondents could be described as traditional, monolingual, and monocultural, oriented to their home area and to the national culture. In comparison to many other countries, including most other EU countries, this group of people almost totally lacking in contact with English forms a small minority, consisting of less than 10 % of the population (cf. Eurobarometer 2006; Pietiläinen 2006).

At the other extreme, among the “have-it-alls” (about 16 % of the total), we find in particular younger respondents (85 % aged under 45), city residents (also 85 %), respondents who have a university or polytechnic degree (60 %), and respondents who are working as managers or experts (60 %). In these people’s lives, the English language has a strong presence: they have studied English for many years, feel they have good proficiency in it, and use it extensively. In this group a smaller than average proportion (69 %) view themselves as monolingual, and correspondingly, many see themselves as bi- or multilingual (31 % vs. 16 % for the total population). The lifestyle of these respondents could, in fact, be described as displaying a multilingual and multicultural “postmodern” orientation, one characterized by mobility, involvement with global cultural trends, and engagement with the new media (Otsuji & Pennycook 2010; Leppänen, forthcoming).

In the light of this reclassification of our respondents, it could also be argued that the particular stance each group takes towards English can be interpreted as indexical of their social welfare. Those who actively use English, have good proficiency in it, and need to use it are more likely to have high social status, a high level of education, and an urban and international lifestyle. We can also say that they are more likely to be youthful and involved in youth culture, have an interest in popular culture, use the new media, and be alert to the demands/opportunities of an increasingly global economy. Interestingly, gender is not part of this division. Throughout the survey there were only minor differences between men and women in knowing and using English, and in attitudes towards it.

In contrast, people who do not have much contact with English do not necessarily have the same opportunities in life. Hence, a lack of or having only limited English skills may be one factor contributing to inequality (see Blommaert 2005). Recent sociological studies in Finland (see e.g. Heiskala 2006; Kainulainen 2006) have, in fact, argued that citizens’ welfare is likely to be best secured by education, by self-development, by an ability to meet the demands of modern work, and by mobility (Rintala & Karvonen 2003). On the basis of the present survey, one might very well add English to this list: even if ignorance of the language and inability to use it are not directly linked to social exclusion or relegation to the fringes of society, they indicate a certain uninvolvement in an increasingly urban, international, and multicultural society in which work is becoming increasingly globalized. This state of affairs is not unique to Finland. For example, Hyltenstam (1999) argued that the growing role of English in Sweden could bring about a societal divide, which in turn could lead to a situation where citizens were unable to manage in society unless they knew English (see also Pütz 1995). In other words, English can be seen as a factor linked to social involvement – a factor to be considered along with the individual’s economic circumstances, social relations, education, and lifestyle.

Nevertheless, it may be that in the future, when today’s young Finns with their good knowledge of English grow up and enter the job market, the situation will be less polarized than the one sketched above (since a correspondingly larger proportion of the population will be able to cope with it in everyday and work settings). At the same time, the social divide related to knowing English may shift to a new location: in the future it may be found between the Finnish majority who have fully adopted English and immigrants, for many of whom English will be an additional language, to be learnt along with the language/s of their new home country.

9.5 The future of English in Finland

Although the survey suggests that Finnish has a stable role in Finnish society, and that overall, English is not actively used by Finns on an everyday basis – or at least not by every segment of society – a closer look at respondents’ views provides a more nuanced picture of the future of English in Finland. A majority of Finns think that English enhances international understanding, even if in the future one will still be able to manage fully in Finnish society without knowing English. The native languages – particularly Finnish – are therefore sufficient in principle.

However, according to the future scenarios identifiable in the responses, the position and importance of English are expected to continue to strengthen, to the extent that English will be dominant in certain areas of Finnish life, sometimes even surpassing the Finnish language. This is especially the case in contexts which are in some way considered international, for example in business, economic life, science, and rock and pop music. Interestingly, these contexts are the same as those outlined in Introduction as the key contexts for the historical development of the spread of English in Finland (see Table 1). It therefore appears that the role of English, as it strengthens, will continue to gain ground in those domains in which it already has a strong foothold. Notwithstanding these scenarios, Finns also strongly believe that Finnish will continue to have a firm position in various areas in society, and that English will not displace Finnish – this is the case, for instance, in literature.

More importantly, as shown also by our qualitative studies (see e.g. Leppänen & Nikula 2007), the role and use of English in Finland constitute a multifaceted phenomenon that cannot easily be described in generalized terms: the forms and functions of English are highly context-dependent and complex. Finns employ English as a resource in social interaction and meaning-making in different ways within different settings and domains, thereby adapting and appropriating their language use to divergent situations of use. In some situations English seems to be becoming a phenomenon that occurs as a matter of course, with English offering means of expression and communicative resources to language users in the same way as those offered by the mother tongue. In particular it is clear that in the language uses of young people, especially in relation to the new media, English may be one of the everyday languages that Finnish young people (or at least some of them) need and use without experiencing the communication as distinctively “foreign”. At the same time, in all of this, the Finnish language still maintains its own undisputed place.

In terms of knowing and learning languages, Finns consider English to be the most important foreign language to be known in the future, and it is considered (even) more important than Swedish. And while they recognize the importance of other languages, only a few serious challengers to English are identified. Those mentioned are typically Russian or German, which have traditionally been important languages of commerce for Finland. It is interesting that Russian is seen as the most likely competitor for English, and not Chinese, which on a global scale is increasing in importance. This is perhaps partly explained by the fact that Russia is a neighbouring country, and also by the increasing number of Russian immigrants and tourists in Finland, resulting in a growing demand for skilled speakers of Russian in Finland. This is in accordance with Graddol’s (2006; see also Bamgbose 2001) findings, which emphasize that knowledge of English alone is not sufficient in a globalized world – not even within English-speaking countries, which are themselves becoming more and more multilingual (Graddol 2006: 118–119). For example, in the business world it can be vital to know the customer’s language if a business deal is to be concluded.

As far as knowing English is concerned, English skills are expected to be important to nearly all population groups in the future. One of the reasons for this is that although the respondents believe that information will continue to be available in Finnish, they predict that people will become excluded from certain areas of life if they do not know English. The areas most commonly mentioned in this regard include international communication, employment, and entertainment.

Regarding future changes in the linguistic situation of Finland it will be interesting to observe whether the ratios of the totally uninvolved, the involved, and those who have fully adopted English (discussed above) will change over time. It may be that the proportion of the uninvolved will decrease when those age groups lacking a nine-year basic education start to diminish, and when the proportion of those who have studied English increases (see section 1.3 in Chapter 1). If this happens, and if English maintains its position as the foreign language most commonly studied in Finland, English can be predicted to become a basic skill expected of every citizen (see also Graddol 2006: 72).

We can also speculate, for example, on whether Finns will begin to view themselves as bi- or multilingual rather than monolingual. In fact, our results indicate that Finns have such positive attitudes towards English, and – among certain groups – use English so actively, that Finland might, even now, be considered a country in which English has the status of a second language (ESL, e.g. Kachru 1985) or of a “third national language” rather than a foreign language (Leppänen et al. 2008). In addition, it may be – as the responses concerning attitudes to code switching hinted at – that the significance of English as an additional language, mixing and alternating with the mother tongue, may also grow. There are many countries in which multilingualism is for many people the linguistic reality in which they operate on a daily basis (see e.g. Heller 2007; Blommaert et al. 2005; Jørgensen 2008). Finland, too, may be turning into a country where at least some of the population (the “have-it-alls”) can, in their communicative tasks, employ selectively all the linguistic resources they have at their disposal without having a sense of utilizing different languages. In this sense, and for these people, English may function as one of the resources they draw on and make use of in meaning-making and social interaction.

9.6 Conclusion

No matter how holistic a picture a survey like ours attempts to give, it is, by necessity, an incomplete account of how things really are. Designing and carrying out a research process always takes time, and therefore its findings are bound to lag behind when the results finally get published. It cannot capture the shifts and complexities of people’s perceptions and attitudes as they respond to the changes taking place in the situations in which they come into contact with English; nor can it capture all the shifts in society at large and its various domains. In fact, a survey like ours should be repeated at regular intervals, as long as it is taken to provide useful information for society, language education, and language policies. Furthermore, given that a survey is always a generic description of a phenomenon, it cannot zoom into all the problems, attitudes, assumptions, and perceptions – which may, in fact, be the really important ones to the respondents. In this sense, a survey is always a partial description of people’s perceptions and attitudes, particularly as these are, in reality, much more ambiguous, multiple, changeable, and situated than any survey can show them to be. The psycho-social reality of perceptions and attitudes – whatever their degree of stability – is that they are also emergent, contingent, and negotiable.

Despite these limitations of the survey method, it is undoubtedly a very useful and economical research tool. For us, a survey, based as it was on the responses by a representative random sample of an entire nation, was the best method to gain systematic and generalizable information about the changing sociolinguistic situation in Finland – a country where the role, visibility, and impact of English have been steadily growing since the early 20th century. In this respect, our survey undoubtedly succeeded in its task: we now have an overall picture of Finns’ perceptions of the role and significance of English in Finland and elsewhere, of their learning and uses of English, and of their attitudes to and predictions about what will happen to English, and about the language situation in Finland in the future.

In addition, the survey also fulfilled its purpose in providing a broad canvas against which the particularities of more situated uses of English can be better understood, helping us to see how general or specific they really are. In addition, knowledge of the general picture makes it possible to pinpoint ways in which individual uses and understandings of English are, in fact, indexical – drawing on, reproducing, or challenging more general notions of English. For example, the material collected for the survey offers good opportunities for further studies: more in-depth analyses can identify different language-user profiles within different social groups. In particular, the youngest age groups, for whom English is a crucial part of daily life, merit more detailed study. It would also be interesting to explore how the respondents’ attitudes towards English correlate with their habits of language use, or their self-ratings regarding their English skills.

This kind of integration of findings by surveys and qualitative studies is, in fact, one of the challenges for the present research team. It is a challenge not only empirically, but also theoretically and methodologically, not least because the interpretation of the results of such studies (representing widely different research traditions) needs to be conducted with care in order to avoid distorting the findings in each of them. The findings of such studies do not necessarily relate to exactly the same phenomena. Nevertheless, if successful, such complementary and integrative analyses can cross-fertilize each other in interesting ways; they can help us to understand how the micro- and macro-level understandings of English relate to each other in a dialogic and indexical manner.

What any survey maker also hopes for is that the findings will have some applicability to society. In the analysis and discussion of our findings we have pointed out some of the implications for language education, educational policies, and language policies. If we had to summarize these implications, they might read something like this: in the light of our findings, language education policies and practices should (1) endeavour to take seriously the interest shown by Finns towards learning foreign languages, and (2) ensure that no one will be marginalized in society, education, and professional life because of limited proficiency in English.

Nevertheless, despite well-founded concerns over language shifts in certain domains (notably academic publishing and higher education), and possible implications of these shifts for language policies, the message of the survey is consolatory, in the sense that there is no reason not to trust the common sense of the general public. While people in general have a positive and liberal attitude towards English, they do not view themselves as shifting or succumbing to English in their own usage. They cherish the mother tongue and have faith in its vitality and stability.

Notes

1 Here we must bear in mind that comparing the results of this survey with those of the Eurobarometer survey is by no means simple: responses

depend substantially on the way the question is posed.

2 When we take into account the margins of error corresponding to the 95 % confidence level, the proportion of people totally uninvolved with English is 4–7 %, while those who have fully adopted English constitute 14–18 % of the target population.

Back to top

|

|